Curing vertigo

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 14, 2010

- Curing vertigo

For several months last year, Sonja Decker had to lie down to sleep with the utmost caution. If she rolled over on to her side — her preferred sleeping position — she would experience the spinning sensation known as vertigo. Despite visits to multiple doctors, nobody could provide her with any relief.

“It was really affecting my quality of life and my ability to sleep,” the 72-year-old Bend woman said.

Trending

When she went for physical therapy for her knee at Rebound Physical Therapy on Bend’s east side, her therapist had to ease her down onto her back gently, so as not to trigger the vertigo. Then during one session, the therapist suggested she see Stuart Johnson, another therapist at the clinic who specializes in inner ear disorders. He conducted a simple test that confirmed Decker had the most common cause of vertigo, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, or BPPV.

Johnson told her there was a good chance he could cure her with a set of basic head maneuvers, and if she wanted, he could perform the treatment there on the spot.

“Yeeeessss!” Decker recalls responding, almost in tears.

Johnson took her head in his hands, turned it 45 degrees, and laid her down with her head hanging off the edge of the exam table. After 30 seconds in that position, he turned her head 90 degrees in the opposite direction. Then 30 seconds later, he asked Decker to roll onto her side and he turned her head a further 90 degrees.

“It was miserable because it caused my vertigo to trigger,” Decker said. “He just kept saying, ‘Keep your eyes open and stay with me,’ and that cured it. One time.”

That night she carefully lay back in bed and turned onto her side. To her surprise, her world did not begin to spin.

Trending

“Honey,” she told her husband, “I’m cured.”

Studies suggest about two to three out of every 100 people will experience BPPV at some point in their lifetimes, including 10 percent of people older than 65. Most cases resolve on their own in a couple of weeks, but many patients can experience the spinning sensation off and on for months.

Most patients and many doctors still aren’t aware that a series of simple head maneuvers can completely resolve the condition and allow people to resume a normal life.

Rocks in wrong place

BPPV is also known as top-shelf vertigo because it’s triggered by head movement, such as tilting the head backward when looking at the top shelf of a cupboard. Patients often experience it when they lean back in a dentist’s chair or at a beauty salon wash basin.

Until about 30 years ago, doctors had no treatment, much less a cure, for the condition. Then Dr. John Epley, a Klamath Falls native practicing in Portland, developed the set of head motions that now has become the standard treatment for BPPV.

Initially his colleagues were not impressed, ridiculing the doctor, even trying to have his medical license pulled. This laying on of hands looked more like a parlor trick than good medicine. When Epley first tried to publish a journal article describing the success he was having with the technique, the journal editors rejected his submission on the basis that it wasn’t based on any valid medical theory.

His theory, however, proved to be exactly right. Doctors now know that BPPV is caused when debris enters canals in the inner ear that control the body’s balance, and that the Epley maneuver removes the debris in 80 percent of patients.

It all starts with a sensory organ known as an otolith, which resembles a hairbrush with rocks stuck on the ends of the bristles. The rocks, called otoconia, are made of calcium carbonate and allow the brain to determine body position. If you sit up in bed, for example, the brush is moved from horizontal to a vertical position. Gravity tugs on the rocks, bending the bristles, which then send a corresponding signal to the brain.

But over time, those rocks slough off and can trickle into one of three semi-circular canals in the inner ear. These canals are oriented at 90-degree angles to each other, like the corner of a box. When you move your head, the fluid in these three canals moves, triggering sensory organs that help the body determine its position in space and maintain balance.

When the rocks get inside these canals, they can interfere with that sensory process, fooling the brain into thinking the head is still moving. The effect is a sensation that you or your room is spinning. Over time, the rocks usually dissolve and the symptoms fade away. But the condition can be debilitating, with even the slightest movement sending the person’s head spinning.

Epley reasoned that if the rocks simply fell into the canals, maybe he could use gravity to get them to tumble right back out. The Epley maneuver he developed resembles the child’s toy where you try to move a marble through a maze by tilting the box. By shifting the head through the right sequence of movements, you can move those rocks all the way through the canal to another part of the ear where they can dissolve without causing any problems.

Eye-opener

So how do practitioners like Johnson know which canal the rock is in and which way to turn the head? This is where it really gets interesting. The inner ear has three functions. Most people could probably guess hearing and balance. But the inner ear also has an important function known as vestibulo-ocular reflex, or in common language, gaze stabilization.

“The vestibular system detects head movement and has a reflex that goes directly from the inner ear to the eye muscles that steer the eye muscles in the opposite direction, the same amount, the same speed, so when your head moves, your eyes can track,” Johnson explained.

Without this reflex we wouldn’t be able to read a sign while walking or catch a baseball on the run. But in BPPV, when the rocks enter the canals, they also impact the eye muscles, creating abnormal eye movements that reveal which canal holds the rocks.

Johnson uses an infrared camera to observe this involuntary eye twitch, known as nystagmus, in complete darkness. If the patient can focus on a target, she can keep the effect from happening. Johnson has his patients wear goggles that put their eyes into complete darkness but allow him to see the movement through the infrared camera. He has the patient lie back from a seated position quickly, which is usually enough to trigger vertigo and the nystagmus.

“The brain thinks the head is turning, so the eyes drift the other direction and then it realizes, no, the head isn’t turning so it snaps back,” Johnson said. “The snapping back is the movement we’re trying to see.”

The direction the eye is moving tells him which canal is being affected by the rocks, and which way to turn the head to get them out.

Local treatment

Johnson is certified in vestibular rehabilitation through the American Physical Therapy Association and Emory University. While there are doctors in the region who perform the technique as well, Johnson said vertigo and BPPV are often poorly managed. Many patients are referred for treatment to Portland. It’s a tough trip for most, since vertigo patients often suffer from motion sickness, too.

“I’m trying to spread the word among doctors that, one, these patients can be treated, and two, they can be treated locally,” Johnson said.

Not all vertigo is BPPV, so Johnson said it’s important for doctors to rule out other causes, including inner ear infections, nerve damage or migraines.

“If they don’t have spinning, I know it’s probably not BPPV,” Johnson said. “BPPV only starts with head movement; it doesn’t start spontaneously. And most of the time, it goes away in less than a minute. If somebody has all those three things, then I know there’s a good chance they have BPPV, and there’s a good chance I can help them.”

Tammi Coleman, another therapist at Rebound, has experienced vertigo intermittently for the past 18 months. Last year, she got up too quickly after demonstrating an exercise for a patient and thought she was going to hit the floor.

“I really noticed it lying in bed,” she said. “The way I describe it is like an ocean wave coming in. You just feel it kind of coming on, and you know it’s going to stop and it does stop in about 15 seconds.”

Now when the vertigo returns, she knows she can get immediate help at work.

“It’s a very easy treatment for a very annoying problem,” she said.

About a third of people treated for vertigo will have another case within a year of treatment, and more than half will have a recurrence within five years. In August, more than a year after her first treatment, Decker felt the spinning start again.

“I rolled over, and it just triggered, just a little bit. I just tried to lie there really still, and I slowly got on my back,” she said. “It just struck terror in my heart.”

She came to see Johnson as soon as he had an opening, but he was unable to trigger the vertigo or the telltale eye movements again. “It’s possible that you started to have some debris trickle down into that canal, and when you moved your head back, it came back out again,” he told her.

Decker was terrified that she might face recurring bouts of vertigo again, but her experience with her first treatment gave her hope that she could once again dispatch it quickly and painlessly. That first night, she kept repeating what she had heard on her first visit with Johnson.

“I just kept saying to myself, ‘It’s benign, and it’s treatable,’” she said.

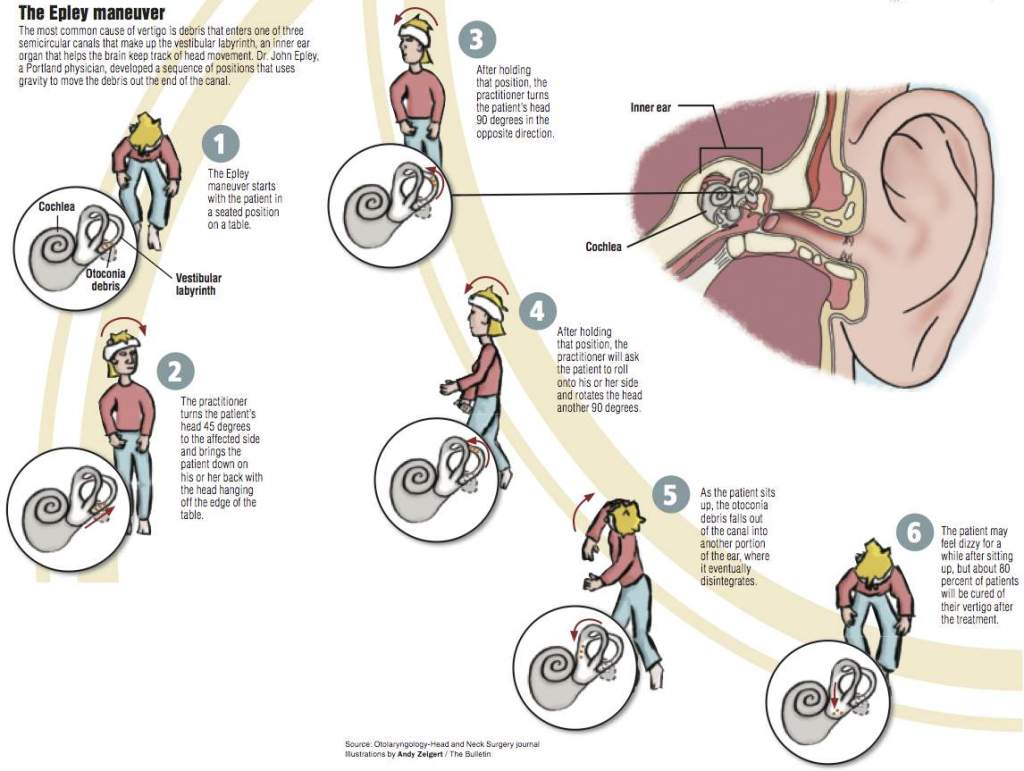

The Epley maneuver starts with the patient in a seated position on a table.

The practitioner turns the patient’s head 45 degrees to the affected side and brings the patient down on his or her back with the head hanging off the edge of the table.

After holding that position, the practitioner turns the patient’s head 90 degrees in the opposite direction.

As the patient sits up, the otoconia debris falls out of the canal into another portion of the ear, where it eventually disintegrates.

Cochlea

Otoconia debris

Vestibular labyrinth

Inner ear

Alcohol consumption and vertigo

Have you ever experienced the sensation called room spins after a night of drinking? According to physical therapist Stuart Johnson from Rebound Physical Therapy in Bend, it’s caused, like most vertigo, by a foreign substance — in this case alcohol — inside the ear canals.

At the ends of each canal are hair receptor cells encased inside a fragile membrane called the cupula. When you move your head, the fluid in the canal pushes the cupula, triggering the hair receptor cells to signal the brain that the head is moving. If you drink enough, alcohol infuses into the canal, changing the density of the fluid outside the cupula, and the cupula begins to billow and move, stimulating the hair cells.

“It makes you think you’re spinning,” Johnson said.

Eventually, the alcohol infuses into the cupula as well, equalizing the density inside and outside of the membrane, and the spinning stops. But as your body starts to clear the alcohol, it clears out faster outside the cupula than inside, once again leading to a difference in density on either side of the membrane.

“There’s going to be another, milder spin that goes the other way,” Johnson said. “But most of us are asleep by then.”

— Markian Hawryluk, The Bulletin