Bachelor restricts hiking up and skiing for free

Published 4:00 am Friday, December 4, 2009

- Bachelor restricts hiking up and skiing for free

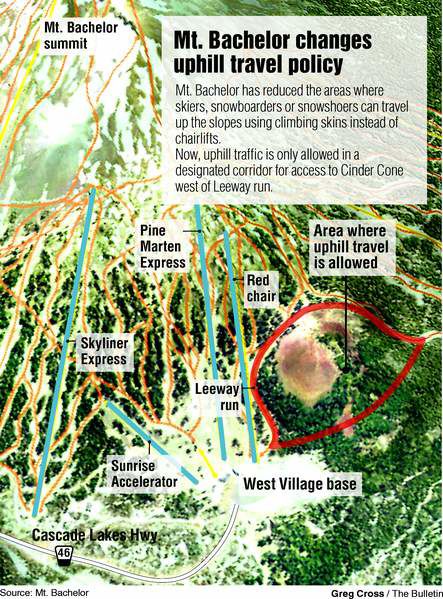

Mt. Bachelor’s 2009-10 operating plan has restricted the areas where skiers, snowboarders and snowshoers can hike uphill instead of using chairlifts.

Ski area officials say the change is designed to increase safety on the mountain, but it has upset some people, who say the move unfairly limits their ability to recreate for free on public land.

Trending

Until this season, snow sports enthusiasts were allowed to travel up the slopes without the help of chairlifts, then ski down. But this year, citing safety concerns, Mt. Bachelor and Deschutes National Forest designated all areas of the mountain, with the exception of a corridor west of the Leeway run that leads to Cinder Cone, as closed to uphill traffic.

The restrictions don’t apply during the offseason, but remain in effect for areas being used for snowmaking or grooming.

The policy change, according to a letter on Mt. Bachelor’s Web site from President and General Manager Dave Rathbun, stems from concerns about avalanche control and grooming operations, and conflicts between down- hill skiers and snowboarders and uphill traffic.

Rathbun said the popularity of hiking on skins and snowshoes has grown significantly over the past few years, and that growth has led to incidents between recreation enthusiasts and mountain staff.

“It’s become quite severe,” Rathbun said.

Rathbun pointed to an incident last winter after a significant snowstorm when staff were operating five groomers on a downhill slope. Rathbun said four people hiking up the center of the trail wouldn’t move out of the way, even after operators turned on sirens and lights.

Trending

“It’s not that we weren’t trying to avoid them, but you literally don’t have the control (with a Sno-Cat groomer),” he said.

He also pointed to a time last year when several people hiked above the avalanche control team and refused to stop climbing.

“They were going up into uncontrolled, known avalanche areas above our team,” Rathbun said. “Somebody’s going to die if that practice continues. Safety is our primary concern.”

While Rathbun said the primary concern is safety, it doesn’t sit well with everyone.

Hunter Dahlberg, 39, has reg-ularly used skins to climb Mt. Bachelor and ski back down since moving here six years ago. This year, he purchased his first-ever season pass.

He said it worried him that the U.S. Forest Service was paying more attention to a large stakeholder like Mt. Bachelor instead of weighing all recreation enthusiasts’ interests evenly.

“There’s other users out there, like the snow machine club (or) the Bend Backcountry Alliance, which started here in Bend a few years ago,” Dahlberg said. “There’s these different groups, and to get anything accomplished takes forever. And then Bachelor makes a call, and they say OK. That strikes me as unfair.”

The Forest Service has a working agreement with Utah-based Powdr Corp., which leases the land from the Forest Service because Mount Bachelor is part of the Deschutes National Forest.

“For the guy who doesn’t have the money or the desire or inclination to pay at Mt. Bachelor, to limit his or her options for using the national forest, that strikes me as just a little heavy-handed,” he said.

Rathbun and the company have received dozens of e-mails from people concerned about the change. Most of the complaints, Rathbun said, express concern about the fact that new restrictions are being placed on public land. Others, he said, point to the fact that there haven’t been any recent or major injuries as a result of the uphill traffic.

The ski area didn’t announce the change, he said, but did include it in its annual operating plan.

“Hindsight is always 20-20, but when it comes to safety that’s what we focus on,” he said. “I’ve not heard anything I haven’t heard before in other places, and I’m not that shocked or concerned by the volume of what I’ve been hearing. We’re going to run Mt. Bachelor in a safe fashion.”

Aaron Talbot, who has 20 years of backcountry skiing experience and often skis before the lifts open at Mt. Bachelor or after they close for the night, thinks there could be a better plan that accommodates everyone.

“I know a lot of (ski) areas have gone through this transition, but I think Mt. Bachelor is a little bit unique in that they’re able to close an entire mountain with this policy,” he said.

Talbot said he would prefer a policy like that of Washington’s Crystal Mountain, which asks uphill travelers to check with ski patrol for closures to places where avalanche control work is under way. The mountain also uses signs that indicate avalanche hazards and asks uphill traffic to keep to the sides of trails.

“Instead of a shotgun approach, it’s more of a sniper approach,” Talbot said, “the sniper approach being more targeted based on what environmental conditions are at the time.”

But Rathbun said that while other ski areas have different uphill access policies, Mt. Bachelor is unique.

“On Mt. Hood there are multiple ski areas, and in between those boundaries and above those boundaries is legit backcountry terrain,” he said. “In Utah, where they get significant light, dry, fluffy snow on very steep terrain, (they) don’t allow any uphill traffic at all.

“Here, what drives our reasoning is the fact that we have a ski area that is 360 degrees in circumference, and 50 percent of our permit area is a skiable area and 50 percent is the terrain below the skiable area.”

For now, the policy remains in effect. On Tuesday, Rathbun will meet to discuss the new policy with Shane Jeffries, district ranger for the Bend-Fort Rock Ranger District. Once the meeting is complete, Rathbun said he will update the Web site with any changes.

“We’re committed to looking at it again,” Rathbun said. “But we’re not going to let the public land access mindset in any way impact our ability to operate in a safe manner.”