Jackson’s moves expressed as much as his music ever did

Published 5:00 am Saturday, June 27, 2009

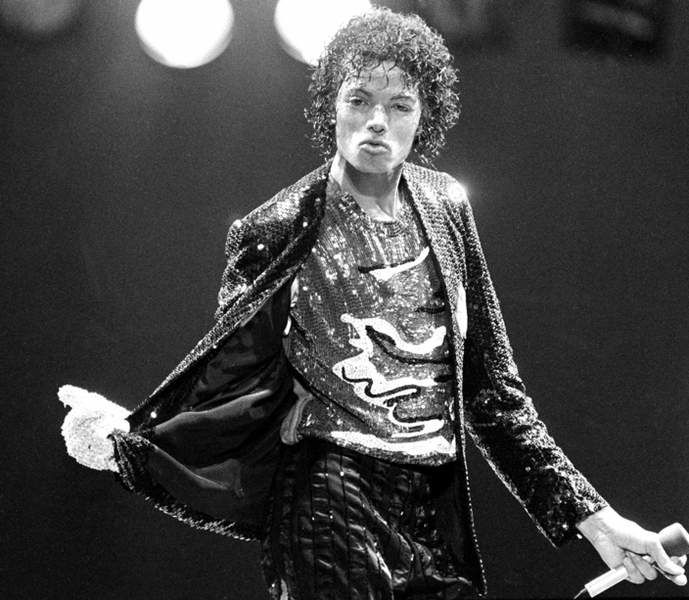

- Michael Jackson appears on stage in 1984 at opening night of his Victory Tour at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles.

Michael Jackson will be remembered as a great and widely imitated mover. Other things about him will be remembered too, but it is amazing how many of them are apparent in his dancing. The sweet boy, the angry dissident and the weirdly glamorous star are all there; and so is the androgyne who gives off conflicting male/female signals in the course of a single number. You can see what he has learned from the urban tensions of “West Side Story,” the disco craze of “Saturday Night Fever,” the jazz-based choreography of Bob Fosse and from a line of divas from Judy Garland to Diana Ross. (There’s even a little Audrey Hepburn there.)

Among the vast array offered by YouTube of clips of his performances, “Michael Jackson’s Best Dance Moves” strikes me as fairly gruesome. It is what it implies: a collage of separate moves arranged to break Jackson’s work up into tricks and special effects, all fitted to a single song. Even in his best work, Jackson relied too often on known stunts: the crotch-grabbing and moonwalking are just the most famous of these, and on too many occasions the audience seems to be waiting for him to do them.

It’s no secret that Fred Astaire — who during the 20th century was widely revered among all dance artists as its greatest dancer — singled out the young Jackson for praise. But Astaire died in 1987, and it’s hard to believe that he would have applauded the later Jackson without extensive reservations. Watch Jackson live at the Super Bowl halftime show in 1993, wearing his trademark dark glasses and ponytail with loose locks falling forward over the brow, starting out in quasi-military uniform, and you see he does everything the audience wants with skill, energy and almost no spontaneity. Even the anger seems synthetic now.

But to watch “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough” (1979) is to be amazed at just how much charm the 20-year-old Jackson had, and the charm gets more infectious as the dancing proceeds. You begin by noticing the pelvis, doing its characteristic pulsation, and you recognize how close you are to the world of John Travolta in “Saturday Night Fever.” Fairly soon, you take in the heels, or rather the action of the insteps that keeps rhythmically lifting the heels off the floor, and then, in various ways, you see the ripple of motion between feet and those very slender hips.

But Jackson was an upper-body dancer too: there’s a marvelous moment here when he tilts back and stays there. Now go to “Billie Jean” in Motown’s 25th-anniversary celebration (1983). You can see that already everything is much more choreographed, both in the bad sense of unspontaneous and the good sense of dance structure. Most of the time his dancing is so aflame you don’t feel any lack of freshness, and he’s so alert that you hardly have time to laugh — though I think you ought, happily — at the way his busy pelvis keeps hoisting his pants up and revealing his off-white socks. (The changing expanse of socks becomes part of the rhythm.)

Jackson was just 24 in 1983, and the androgyny was already evident. When he shows us the debonair angle at which he can wear a hat, he’s much more like Garland than anyone else; when he splays his hands and bends his knees in jazz effects, he recalls the chic archness of Hepburn in “Funny Face,” and toward the end those feet of his go right up onto point; and in between he gives us some early hints of his later macho crotch-grabbing.

Yet all this is not to mention the moment in the “Billie Jean” Motown show, when he stops singing and sends the audience, justifiably, wild: the moonwalking, whereby he slides briskly backward while giving the impression of walking emphatically forward. He doesn’t overdo it — about five paces, on two separate occasions — and it’s a thrill, both times. By the end, you’re amazed at this marvelous young mass of contradictions.