Meet the people behind the numbers

Published 4:00 am Sunday, February 1, 2009

- Meet the people behind the numbers

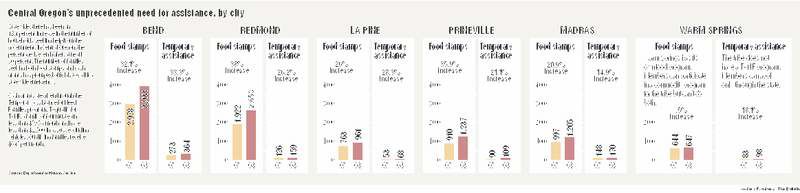

Department of Human Services employees say they’ve never seen anything like it. Every month, the number of people seeking assistance rises. In December, 10,636 families in Central Oregon received food stamps. Statewide, they are calling it an emergency. But in Central Oregon, they are looking for an even stronger word. With a 29.5 percent increase in families receiving food stamps in December compared with December 2007, the tri-county area is the hardest hit in the state, when measured by the increased request for food stamps. Many families and individuals are seeking help for the first time in their lives, others are finding they need more. Below, a few of those people agreed to share their stories.

Jeff Johnson

Jeff Johnson’s chicken Parmesan dinner expired 22 days ago.

In about a month’s time, he went from buying fresh foods at the grocery store to getting free, slightly expired food.

A recent divorce came at a time when the 45-year-old, self-employed residential and excavation construction worker was experiencing slow times.

The Bend resident went from living in a 2,552-square foot, five-bedroom, three-bathroom home on 40 acres, to a 35-foot fifth-wheeler in his church’s parking lot.

Now, the man who lives in a $42,000, 2006 Weekend Warrior, which he bought with visions of traveling the state with his family, is answering questions he never dreamed someone would ask him.

“How are you meeting your basic needs?” asked Department of Human Services employee Sue McDonald — a stranger to Johnson.

His face flushed, Johnson shared the story of his first visit to the food bank, of living behind his church, of borrowing $20,000 from his parents.

“Do you have any income?” she asked. The answer was no.

She asks about assets.

“It’s kind of hard driving a 2006 Chevy pickup to a food bank,” he said.

He tried for military benefits but was told by officials in the Veterans’ Affairs office he was 33 days short of continuous active duty to qualify.

On Wednesday, he decided he needed more help than he could get from the food bank and applied for state assistance for the first time in his life.

McDonald gave him a list of resources, places to go for transitional housing, for clothes, for extra food.

“Food stamps weren’t intended to carry anyone through today’s economy,” McDonald told him. “They don’t last a month.”

In 2006, Johnson’s gross annual income was $170,000. His house, then appraised at nearly $1.2 million, was $70,000 away from being paid off.

“There have been slow stretches during the last couple of winters,” Johnson said. “But not like this. This is just incredible.”

It’s an odd feeling, Johnson said, to own expensive goods that aren’t worth anything. He tried selling his tools at Trade-N-Tools, where you can trade tools for money. But he quickly found out he wasn’t the first one with the idea; the place was inundated, he said.

He was never irresponsible with money. He planned ahead. He had a savings account, but that was wiped out by lawyer’s fees.

His parents, who also live in the area, are using their savings to help their son.

“I grew up with parents that never took vacation; we drove a station wagon with a red-front fender. It was all mismatched and had snow tires on it year round,” he said, adding he intends to pay back every dime his parents have given him.

Although Johnson never dreamed he would be in this position, he said, he’s being proactive about surviving. “There’s just no income. I just can’t get any money …” he said. “But it’s easy to find people in worse shape than me.”

Joel Hall

Joel Hall would like to leave Bend — but he can’t.

“There are more job opportunities elsewhere … But I can’t afford leaving,” he said. “The economy’s impact on a small town like this …”

When he first moved to the area, in 2005, 37-year-old Hall worked for the Bend-La Pine School District as a teaching assistant.

He has a bachelor’s degree in education from California State University- San Marcos.

Hall was laid off from that job. He was laid off from Flatbread Pizza. He’s been a bartender but was laid off there as well.

”It was tough five years ago finding a job in this town,” he said. “Now, this town that seemed to explode for a while, it’s just imploded.”

He’s getting by teaching snowboarding a few hours on Mt. Bachelor. But that’s only about two hours a week. And he hasn’t received unemployment benefits yet, because he’s been told it’s a four- to six-week wait.

“In the meantime, there’s no income,” he said while waiting in line for food stamps on Wednesday. He’s dressed in all black, with The North Face sneakers. He’s clutching an issue of National Geographic magazine. “I wouldn’t be standing in this line if that wasn’t the case.”

Hall has moved in with a friend to reduce expenses.

“Thank God I have good friends,” he said. “But they are losing their jobs, too, and they have educations. They are lawyers …”

Maybe, he said, it’s time for a career change.

“I would like to get into a field that can withstand this stuff,” he said, mentioning health care as a possibility.

Wednesday was his first time applying for food stamps.

“I never though there would be this many people here,” he said, after waiting in line for about 40 minutes. “But it seems to be hitting people from all directions.”

Although Hall said he’s determined to stay optimistic and keep his head up, it was a difficult decision for him to visit the DHS office.

“I’m totally embarrassed,” he said. “I didn’t want to come down here and wait in this line. But six weeks with no income … I check Craigslist and the paper all the time. There’s just not much out there.”

Kris Hakkila

As soon as Kris Hakkila, 44, of Bend, noticed his work drying up, he started applying for jobs.

He has yet to hear from anyone. In December alone, he sent out 40 résumés, looking for jobs at flooring manufacturing companies or as a project manager on different jobs — without a single call back.

“Not a thing, not a letter, not a call,” he said. “You just know they are being bombarded with applications.”

And so, on Wednesday, the self-employed hardwood floor contractor applied for food stamps for the first time.

His sentiments echoed many others at the DHS office.

“I’ve been through tough times,” he said. “But never this bad before.”

Along with his wife, who works as an assistant to a financial broker, Hakkila has two daughters, 14 and 17.

“All our money is going to pay our bills,” Hakkila said. “Soon, we’ll have absolutely nothing.”

Two years ago, his business was bringing in around $60,000. He has a job lined up in March, but other than that his income is close to zero.

He’s never even thought of applying for food stamps before. And he waited until there were no other choices.

“You know, it kind of sucks,” he said.

Karen Albert

Nearly every weekday morning, Karen Albert took the Les Schwab Tire Centers shuttle from Prineville to her office at the company’s new headquarters in Bend.

But last Friday, she decided to drive her own car.

An hour into her workday, at 8 a.m. her boss called Albert into an office. The human resource director was waiting.

“They told me they were letting me off due to the economy,” she said.

The 48-year-old didn’t see it coming.

“They told us they were done with layoffs.”

Albert was one of 25 people laid off a couple of weeks ago. Earlier this month, the company also laid off about 25 people.

“I just called my daughter and cried,” Albert said.

Since she drove her own car, she didn’t have to wait until her shift was over for the shuttle to arrive and ride home with her former co-workers.

“That was lucky,” she said. “I’m trying to find the blessings in all of this.”

She drove home and cleaned the house.

“And then I went online and applied for unemployment benefits,” she said.

Albert worked for the tire company — Central Oregon’s second-largest private employer — for five years.

A single mom with no other income, Albert immediately thought of her two children, ages 21 and 19. Her daughter, the oldest, has rheumatoid arthritis. And her youngest, a son, is a wrestler in college.

On Wednesday, Albert sat in the Prineville office filling out an application for the Oregon Health Plan.

“Amy can’t go without medical coverage, and my son is on the wrestling team,” she said. “If I don’t have coverage, I don’t care, but they need to be covered.”

Albert said she’s hoping the insurance coverage will be the only assistance she needs.

“I was raised in a family where you don’t ask for help. You take care of yourself,” Albert said. “So it’s rather humiliating. But you do what you have to do to take care of your family.”

Mona Meeds

Mona Meeds didn’t want her children to know.

But she mentioned food stamps while speaking to her husband, and her children heard.

“I didn’t want them to be embarrassed,” said the 31-year-old mother of four.

“If I hadn’t mentioned the Oregon Trail card, they wouldn’t know,” she said.

The Oregon Trail card is a debit-like card that makes food stamps available electronically.

When it became harder and harder for her husband, who owns his own heating and cooling business, to find work, Meeds knew she had to apply for help.

“The work just isn’t there,” she said. “During the housing boom, there was so much work.”

She applied for food stamps and signed her children up for the free and reduced-lunch program.

Without the aid, she’s not sure what would happen. Savings are gone, and her husband continues to take jobs farther and farther away from Prineville.

Even though she is constantly on the move, picking up and dropping off her children, ages 5, 11, 14 and 15, she applied for a job at Rite-Aid.

“It’s the only job I’ve seen posted,” Meeds said. “But they didn’t call.”

Four years ago, the family built a home and had money in the bank.

“Now, I try not to think about it,” she said.

Her children took the news well.

“I told them Dad doesn’t have much work and we’re getting assistance. When it gets better, we’ll get off of it,” she said.

With Crook County’s unemployment rate recently reaching 14 percent, Meeds said her children took it well, in part because they are familiar with tough times.

“They took it better than I thought,” she said. “They have a lot of friends that are having hard times too.”

Keshia Yaw

Keshia Yaw sat in the Department of Human Services office in Madras on Wednesday, waiting for her mother to pick her up.

“I know what I’m going to do,” said the 18-year-old single mom from Warm Springs. “I’m going to find a job, work on scholarship forms, get re-accepted to COCC (Central Oregon Community College) and transfer to Portland State.”

Maybe, she said, she would study something in the medical field.

Although, she doesn’t like asking for help, Wednesday was the first step in realizing her goals.

A blue folder, full of information, was on the table in front of her. Inside was information on how to receive cash assistance from a program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The cash grants are $647 a month for families of four that earn less than $795 a month and have less than $2,500 in assets.

More than money, she’s hoping the program will help her get a job. The goal of the temporary assistance program is to create self-sufficiency for participants. To receive benefits, job searches are mandatory. And the individual must participate in the services available — such as job training classes that help with résumés.

Yaw lives with her mom, who receives food stamps and disability. She doesn’t have her driver’s license. It was too expensive, so any job needs to be near home.

“I don’t like it, depending on other people,” she said.

Yaw wasn’t the only young face at the Madras DHS office on Wednesday. Vicky Higgins, the operations manager, said her office serves a large teenage population.

In 2007, the office helped nearly 40 homeless teenagers.

“The biggest increase is those people who have never asked before,” Higgins said. “But the teen population is really increasing, too.”

Basilio Gomez

For the past 12 years, Basilio Gomez has worked at Bright Wood, in Madras.

He’s no stranger to the economy impacting the hours he works.

When times are good, the forklift driver is guaranteed 40-hour workweeks at the wood remanufacturing company. But lately it’s impossible to work enough hours to support his wife and four children.

On Wednesday, the 44-year-old applied for more food stamps and filled out the paperwork to put his two older children, ages 12 and 11, on the Oregon Health Plan.

The younger two children are already covered through the plan.

He has insurance through the wood manufacturing company, but the deductible is too high.

“It’s bad this year,” Gomez said.

Jaimie and Dave Crockett

Since September, Jaimie Crockett, 25, of Jefferson County, has been taking her résumé to any grocery store and gas station she can drive to.

“I’m trying to find anything,” she said.

Her husband, Dave, 36, was demoted from a salaried to hourly position at Bright Wood, Central Oregon’s third-largest private employer. During a recent week, he only worked 16 hours. He’s been with the company for 14 years.

The couple waited Wednesday in the lobby of the DHS office in Madras for an appointment with a caseworker, who will explain how to apply for food stamps.

Dave never imagined it would come to this point.

“A couple of years we went through this at Bright Wood,” he said. “But that was for a month.”

The couple has two daughters, ages 7 and 2.

“This is horrible,” Dave said. “I’ve never had to ask for help for anything.”

In September, Dave was bringing home about $3,000 a month. The money went to house payments and groceries. Last month, his income was $1,000.

Although Jaimie doesn’t like it, she has an easier time asking for help.

“I’m willing to do whatever to put a roof over our kids’ heads,” she said.

Dave is also studying accounting at Central Oregon Community College, so there are student loans to pay. He’s hoping it’s a recession-proof job.

As the mortgage payments pile up, the hardest part, Jaimie said, is not knowing if they will be able to stay in their house.

“We need to have a safe, comfortable place for our kids,” Jaimie said. “And that’s in jeopardy. If I didn’t have kids, it would be different.”

They are hoping the food stamps can alleviate some of the grocery bill costs so they can put more money toward paying off their house.

“I just kept thinking we could do this on our own,” Dave said.

But they couldn’t.

“We tried to put it off, but it caught up with us,” Jaimie said. “We couldn’t think about it anymore; we just had to do it. So here we are.”

t

t

t

Sources: Department of Human Services, Oregon Employment Department

Sources: Department of Human Services, Oregon Employment Department

*Increases from December 2007 to December 2008. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program gives cash grants to qualifying families.

Sources: Department of Human Services, Oregon Employment Department

*Increases from December 2007 to December 2008. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program gives cash grants to qualifying families.

*Increases from December 2007 to December 2008. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program gives cash grants to qualifying families.

*Increases from December 2007 to December 2008. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program gives cash grants to qualifying families.

In order to receive benefits in a timely manner, the Department of Human Services asks applicants to bring all necessary information and identification. That includes photo ID, Social Security number and a payroll stub or other proof of recent income.

Through DHS’ self-sufficiency program, food stamps, the Oregon Health Plan, cash grants and assistance for victims of domestic violence are available.

• For food stamps, families can have an income of as much of 185 percent of the federal poverty level. For a family of four, that’s $3,268 per month or an annual income of $32,568.

• For cash grants from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, a family of four must earn less than $795 a month and have less than $2,500 in assets, excluding vehicles.

Check the agency’s Web site, www.oregonhelps.org, to see if you are eligible for benefits, or visit your local DHS office. Applications can be downloaded at www.oregon.gov/DHS/assistance.

Sources: Department of Human Services, Oregon Employment Department