Memoir is a window to U.S. capital’s history

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 8, 2009

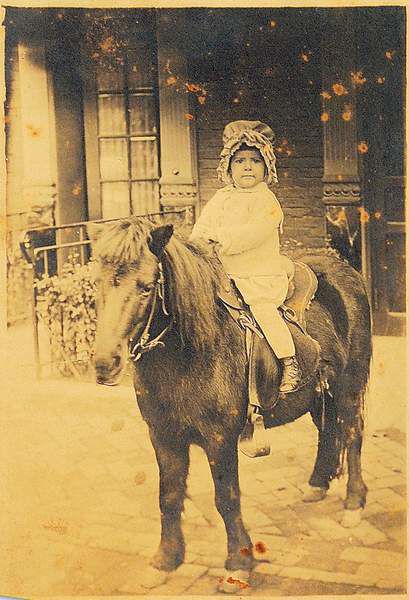

- Washington Post photo by Nikki Kahn

WASHINGTON — For two years, Mary Z. Gray sat at her typewriter by the big window in her cluttered den, a servant to ghosts of her past: lamplighters and icemen, newsboys and fruit vendors, ragmen and undertakers. All denizens of old Capitol Hill, clamoring for a place in her manuscript.

Now, at 90, she is finished with them, or mostly so. They reside on 228 pages in a plain maroon binder that sits, untitled, on the dining room table — content, so to speak, with release from her memory.

They populate a work that is part memoir, part reverie about places, past and present. It is also a vivid sketch, through the eyes of her childhood, of life on Capitol Hill in the 1920s and ’30s.

It was then a marvelous, quirky neighborhood where her father’s funeral home had a speaking tube at the front door where people whistled for the undertaker. It was a place where a washerwoman brought clean laundry in a baby carriage with a bent wheel.

And it was a place where Gray was the nearsighted little girl with a squint whom everyone called Sissy.

A story that needed to be told

Gray, a retired journalist and former White House speechwriter who left Capitol Hill a lifetime ago, said she did not choose this part of her life to write about.

“It was as if it was chosen for me,” she said. The idea came when a search for a parking place with her daughter two years ago landed them in her old haunts. There she was, decades removed; yet the places remained, like old friends.

Once she started writing, the story poured out. “Every night when I went to bed, it came unbidden,” she said. “And I couldn’t turn it off.”

The project was unhindered by her age. “I don’t think in terms of being too old,” she said. “That just is not part of the equation.” And she was undisturbed by technology. She has no computer or cable TV.

So, sitting at her manual Olivetti in the house in suburban Maryland where she has raised two children and lived for 55 years, the former freelancer for the New York Times and Washington Post began.

One of her earliest memories was of a role she had as a child growing up above the family funeral home two blocks from the Capitol.

At night she would to go to a window in the third-floor apartment and see whether the light was on in the columned tholos atop the Capitol dome. If it was, she’d announce to her family: “They’re in session!”

The light meant Congress was working late, and it was a beacon as evening fell over the neighborhood.

Then there was the strange whistling tube for funeral customers.

“Papa would get out of bed and whistle down the tube, followed by an assurance that he was on his way,” she writes. “And off he’d go, in slippers, robe and pajamas.

“We had telephones in the Twenties,” she writes. “Why did someone have to come in person to request the undertaker’s aid? And why this archaic instrument at the front door?”

Much of her childhood was spent at the Charles S. Zurhorst funeral home, a business founded by her great-grandfather in the 1860s, at 301 East Capitol St. She lived with her parents and older brother over the second-floor “parlors.”

Care had to be taken when there was a funeral downstairs. The children walked softly, and her mother would refrain from playing their piano, instead running her fingers through the air over the keyboard.

When the services were over, a call would come from downstairs: “They’re gone.” Her mother would take to the piano and celebrate by singing from a Verdi opera, and the children would stomp joyfully around the apartment.

Colorful characters, but not all was rosy

Gray’s story is filled with characters — her great-grandfather Augustus Wilhelm Schroeder, who was in the Marine Band and played for Abraham Lincoln; her father, Charles, a journalist who was summoned home from a Chicago newspaper to run the funeral business; and her mother, Edwinetta, who had a beautiful soprano voice but whose husband and father would not let her pursue a career onstage.

Outside, there were more characters. In summer, fruit and vegetable vendors hawked “straaaaaawberries” and “woedamelon,” she writes. The iceman came in a horse-drawn wagon and used tongs to hoist the huge blocks. People scrawled how many pounds they wanted on a piece of cardboard and posted it in a window.

The ashman walked in through the unlocked door to take coal ash from the furnace. The lowly ragman appeared from an alley with a pushcart. And the photographer with the pony would snap people’s pictures in the saddle — as he once did Gray’s. But they never got a ride.

People ate scrapple and hominy with applesauce, potato cakes and venison steaks, squab (baby pigeon) on toast and frozen macaroon mint balls with hot fudge sauce, she writes.

Yet just beyond the facade lurked the issue of race in segregated Washington. The neighborhood’s black residents and workers did not seem entirely real to a white child, she said.

Gray writes of her family’s black washerwoman, who would bring the laundry in the broken baby carriage.

“I wonder how much she was paid to hand-wash, hang-dry and iron these mounds of linen,” she writes.

“And where were they going, the ragman, the ashman, the washer woman, and others without faces or names who did our dirty work and then disappeared up the alley and out of our world?”

Asked whether Capitol Hill was a better place then, she thought for a moment and said no. Despite the charm and the fascinations for a little girl, there was an overabundance of poverty, disease and racism.

“I know some people who think everything was just so much better in the old days,” she said. “That’s a lot of baloney.”