Marsters machine helps deaf people communicate

Published 5:00 am Sunday, August 23, 2009

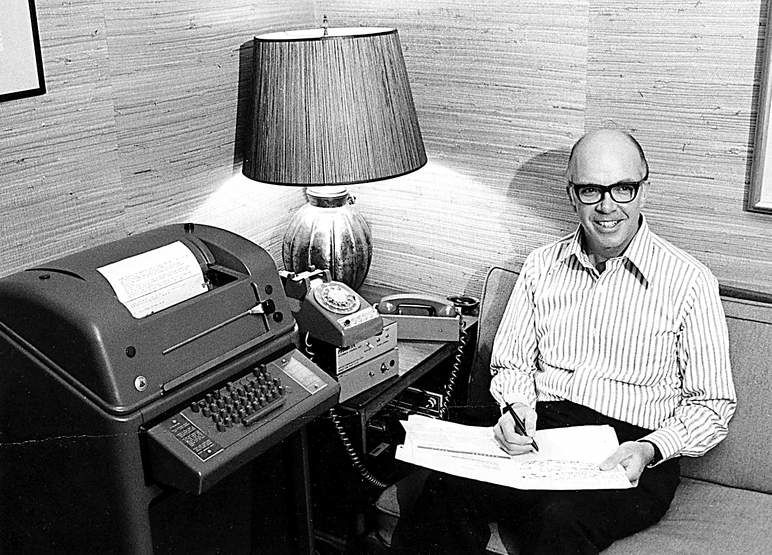

- James Marsters, shown in Pasadena, Calif., in 1971, and two colleagues converted a Teletype machine into a device that could relay a typewritten conversation through a phone line the first example of what became known as a TTY.

Sign language, lip reading and speech training helped James Marsters get through college and dental school and made it possible for him to succeed as an orthodontist. He could communicate very well face to face.

But for most of his first 40 years, the telephone was a barrier.

All of us in the family, whenever a call came for my dad, his son James Jr. said Friday, we picked up this handset attached to the phone so that we could listen in and relay to my father what the caller was saying.

Marsters and two deaf colleagues broke that barrier for themselves and tens of thousands of other hearing-impaired people in 1964 when they converted an old, bulky Teletype machine into a device that could relay a typewritten conversation through a telephone line. It was the first example of what became commonly known as a TTY and is now, in a greatly updated and compact version, called a text telephone.

Marsters died of natural causes at his home in Oakland, Calif., on July 28, his son said. He was 85.

A mutual acquaintance introduced Marsters to Robert Weitbrecht, a physicist at Stanford University, in 1964.

Weitbrecht came up with the idea of using an acoustic coupler now called a modem to connect two Teletype machines. The coupler changed electrical signals coming from one machine into tones sent through a phone wire; at the other end, the tones were changed back into electrical signals so that the message could be printed on the receiving machine.

Another tinkerer, Andrew Saks, an electrical engineer, was soon working in the garage as well. Marsters and Weitbrecht had gone to him for financing.

With the intention of building a network of TTY users, the three men began collecting and reconditioning discarded Teletype machines. They formed a company, Applied Communications Corp., to refurbish and donate TTYs. Marsters traveled around the country, educating the deaf community about the new technology, forming partnerships with other organizations and lobbying for support from government officials.

There were only 18 TTYs in operation in 1966, Karen Peltz Strauss, the author of A New Civil Right: Telecommunications Equality for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Americans, said in a telephone interview. By 2006, there were about 30,000 listings in the Blue Book, a national directory of TTY users.

Marsters, she said, got the ball rolling for future generations of people with hearing loss to achieve telecommunications equality.