Sludge remains in Indian city with a toxic history

Published 5:00 am Monday, July 7, 2008

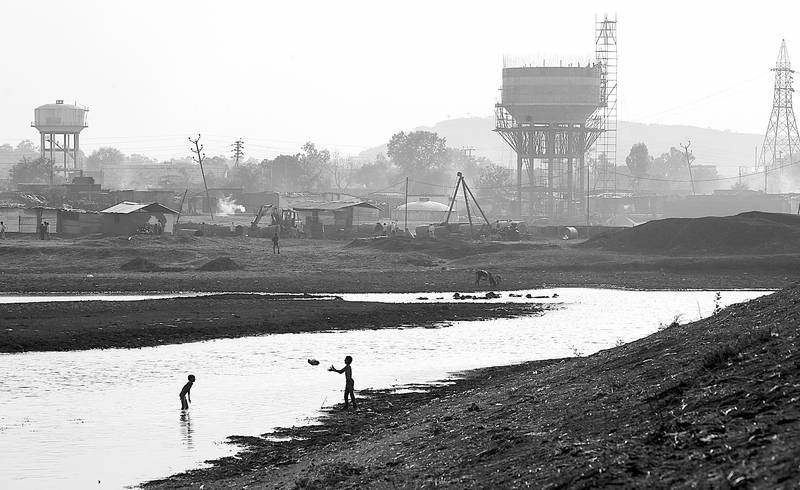

- Boys play in a pond that once served as a repository of chemical sludge from the old Union Carbide plant, background, in Bhopal, India. The pond was once sealed with concrete and plastic, but in the searing heat, the concrete cover eventually collapsed.

BHOPAL, India — Hundreds of tons of waste still languish inside a tin-roofed warehouse in a corner of the old grounds of the Union Carbide pesticide factory here, nearly a quarter-century after a poison gas leak killed thousands and turned this ancient city into a notorious symbol of industrial disaster.

The toxic remains have yet to be carted away. No one has examined to what extent, over more than two decades, they have seeped into the soil and water, except in desultory checks by a state environmental agency, which turned up pesticide residues in the neighborhood wells far exceeding permissible levels.

Nor has anyone bothered to address the concerns of those who have drunk that water and tended kitchen gardens on this soil, and who now present ailments from cleft palates to mental retardation among their children as evidence of a second generation of Bhopal victims, though it is impossible to say with any certainty what is the source of the afflictions.

Why it has taken so long to deal with the disaster is an epic tale of the ineffectiveness and seeming apathy of India’s bureaucracy and of the government’s failure to make the factory owners do anything about the mess they left. But the question of who will pay for the cleanup has assumed new urgency in a country that is increasingly keen to attract foreign investment.

It was here that on Dec. 3, 1984, a tank inside the factory released 40 tons of methyl isocyanate gas, killing those who inhaled it while they slept. At the time, it was called the world’s worst industrial accident. At least 3,000 people were killed immediately. Thousands more may have died later from the aftereffects, though the exact death toll remains unclear.

More than 500,000 people were declared to be affected by the gas and awarded compensation, an average of $550. Some victims say they have yet to receive any money. Efforts to extradite Warren Anderson, the chief executive of Union Carbide at the time, from the United States continue, though apparently with little energy behind them.

Advocates for those who live near the site continue to hound the company and their government. They chain themselves to the prime minister’s residence one day and dog shareholder meetings on another, refusing to let Bhopal become the tragedy that India forgot. They insist that Dow Chemical Co., which bought Union Carbide in 2001, also bought its liabilities and should pay for the cleanup.

“Had the toxic waste been cleaned up, the contaminated groundwater would not have happened,” says Mira Shiva, a doctor who leads the Voluntary Health Association, one of many groups pressing for Dow to take responsibility for the cleanup. “Dow was the first crime. The second crime was government negligence.”

Dow, based in Michigan, says it bears no responsibility to clean up a mess it did not make. “As there was never any ownership, there is no responsibility and no liability — for the Bhopal tragedy or its aftermath,” Scot Wheeler, a company spokesman, said in an e-mail message.

Beyond who will pay for the cleanup here, the question is why 425 tons of hazardous waste — some local advocates allege there is a great deal more, buried in the factory grounds — remain here 24 years after the leak.

There are many answers. The company was allowed to dump the land on the government before it was cleaned up. Lawsuits by advocacy groups are still winding their way through the courts. And a network of often lethargic, seemingly apathetic government agencies do not always coordinate with one another.