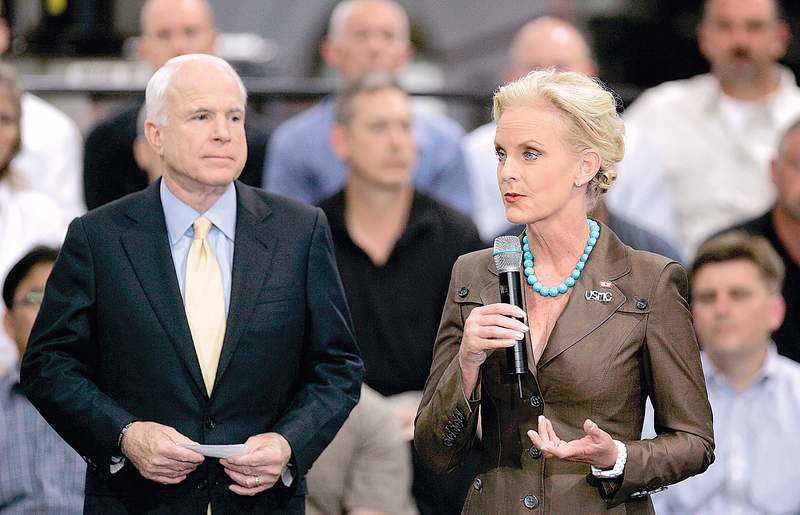

Cindy McCain plays supporting role as husband takes national spotlight

Published 5:00 am Thursday, July 24, 2008

- Cindy McCain introduces her husband during a campaign stop in Michigan earlier this month. The Arizona native overcame her fear of small planes (especially campaign ones) by learning to fly, but during her husband’s run for the White House, she has stood quietly to the side, feet firmly on the ground.

WASHINGTON — Cindy McCain might yearn to be invisible sometimes, or, at the very least, not surrounded by the Secret Service, photographers and gawking people. The scrutiny seems too much to bear. Something about that half-apologetic manner.

“I appreciate you disrupting your day,” she tells one administrator of a Harlem charter school during a June visit to New York, even though a visit by a potential first lady is a big coup for this little school.

“I’m sorry to interrupt your work,” she tells a class of frisky fourth-graders, who are thrilled to be interrupted.

Cindy McCain, 54, ethereally slender in a satiny taupe suit, half-stoops at a respectful distance to observe the children. She’s been a candidate’s wife for almost the entire course of her 28-year marriage. She looks perfect for the part.

That perfection is a theme that repeats itself in interviews with those who know her — this woman who hid her drug addiction from her husband for years, who fought her fear of campaigning via small planes by getting her pilot’s license without telling her husband. There’s a slight self-consciousness in her manner — some combination, perhaps, of guardedness and careful manners and the learned posture of a child dancer.

As she’s leaving, a girl asks for an autograph. She obliges, and a minor riot breaks out as the other children try to get their own and the teacher tells them, “You can photocopy it.” She slips out the door, having left her mark in the impermanence of No. 2 pencil: “Thanks for having me. Cindy McCain.”

• • •

Cindy Lou Hensley grew up an only child in an upper-class section of Phoenix. Her dad, Jim Hensley, founded what became a large Anheuser-Busch distributorship, and her mom, Marguerite, was a proper belle who emphasized impeccable manners. Today, her wealth may exceed $100 million. “She was the apple of her father’s eye,” says her friend of 22 years, Sharon Harper. Marguerite Hensley was “very protective of Cindy. I don’t think she got away with too much when she was in high school.”

The young Cindy rode horses and studied dance and went to public school. She became a junior rodeo queen. Even during the awkwardness of adolescence she had “perfect” grades and a “perfect” look, according to women who went to middle and high school with her. Robin Thurman remembers her from their Presbyterian church.

“She was always impeccably dressed and such a lady,” Thurman says. “I remember sitting in these metal chairs in a circle in Sunday school and just staring at her, going, ‘God, she’s gorgeous.’”

John McCain had much the same reaction at a party in Honolulu in 1979. He was working as a naval liaison to the Senate and, by some accounts, was separated from his wife, Carol Shepp, who’d raised their three children alone during her husband’s 512 years as a North Vietnamese prisoner of war. (Years later, John McCain would acknowledge what biographer Robert Timberg called “dalliances” after his return from war.)

Peter Lakeland, then a staff director on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, remembers how McCain, 42, walked across the ballroom like a “guided missile” toward the young blonde. Cindy, 24, was there with her parents. She’d earned a master’s degree and was teaching disabled children in Phoenix.

Lakeland says: “He had just come out of hell, and his marriage had fallen apart, and I think he really saw Cindy as a chance to really begin over again.” They married in 1980.

“You just can’t just help but love her, honey,” says John McCain’s 96-year-old irrepressible mother, Roberta. “I don’t see any chink in her armor, and I’m not biased.”

• • •

Cindy McCain is a careful, watchful person. She is “reserved,” friends say. She is “shy.” In stories she tells about herself, she comes across as trying so hard not to impose her problems on her husband and others that she can seem self-abnegating. She talks often about her unease in the spotlight and her hesitation over both of her husband’s presidential runs.

“Our married life began almost as quickly as our public life did,” she once told The Baltimore Sun, recalling how her husband ran for Congress shortly after their wedding. She has refused to become a Washington wife, however, and chose not to raise their children there.

During this campaign, Cindy McCain has done few large events on her own. She steers clear of policy. Her brother-in-law Joe McCain says she is a self-editor who recognizes that everything she says must be carefully framed lest it be taken out of context: “The best way to put it in context is to not say it.” In recent months, she has been choosy about her press, granting interviews to the Chicago Tribune and Vogue but not the Arizona Republic, to “Access Hollywood” but not USA Today. The McCains declined interview requests for this article.

Earlier this year, after a New York Times story raised questions about his relationship with a female lobbyist, John McCain called a press conference to deny the romance, with Cindy resolutely at his side. “My children and I not only trust my husband, but know that he would never do anything to not only disappoint our family, but disappoint the people of America,” she said. “He’s a man of great character.”

Staff and friends are exceedingly protective of Cindy McCain. They emphasize her strength but discuss her guardedly, as if she were fragile. Some of her friends said they needed the campaign’s permission before they could talk. Two of her closest friends were made available only under the condition that a press aide could listen in on the interviews.

On “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno” in April, she was poised and funny, but the anecdotes she recounted were unintentionally revealing of distance and secrets in the marriage.

She again shared the story of her addiction nearly 20 years ago to prescription painkillers, which she said her husband did not know about until after she’d kicked the habit. And she told about her husband’s 1986 Senate race, when she knew she’d be flying all over the state in a tiny plane. She was afraid, so she earned her pilot’s license and bought an airplane — all without ever telling him.

“She’s a problem solver,” says longtime friend Harper. “That is a strong way to get over fears.”

Harper uses the word “strong” or “strength” five times in an interview to describe her friend, invoking it to describe, for example, how she didn’t know about the addiction and how her friend “stepped up, made the change by herself.” Friend Lisa Keegan, an education adviser in both McCain presidential campaigns, recalls that Cindy McCain was “pretty private” about her 2004 stroke shortly after it happened. “I had the impression that Cindy was happy to talk about it after she’d conquered it, and not when it was frightening,” Keegan says. “She’s less inclined to want to be asking people to help her.”

Cindy McCain had several miscarriages before she gave birth to Meghan, now 23 and blogging about her dad’s campaign; Jack, 22, at the Naval Academy; and Jimmy, 20, a Marine who has served in Iraq. The couple also adopted Bridget, now 17.

While vacationing in Micronesia, she saw the appalling state of a hospital there. So in 1988 she founded the American Voluntary Medical Team, which sent doctors and nurses to the Third World. Around this time, John McCain was implicated in the Keating Five savings and loan scandal, though ultimately was cleared of any ethics violations.

As she tells it, the stress of this scandal, plus spinal surgeries for two ruptured discs and the pain of an enlarged uterus, all fed her addictive behavior. She has said she did not tell her husband about her growing problem, even as she was stealing painkillers from her medical organization. By 1992, she wrote later in Newsweek, she was taking 10 to 15 pills a day.

Close friend Betsey Bayless, a hospital executive and former Arizona secretary of state, says she detected nothing wrong at the time. “She told me many times that she wanted to be the perfect wife and mother,” Bayless says. “And she pretty much was … but, you know, she had to come to the realization that everything isn’t perfect. She wanted to be the best possible Mrs. John S. McCain as she could,” Joe McCain says. “I think she honestly felt that she did not want to be one of his problems.”

• • •

In 1994, after the Drug Enforcement Administration began looking into medication missing from her charity — and Cindy McCain’s recent addiction became front-page news in Arizona — Joe McCain says he saw the self-control fall away, briefly. He called the house in Phoenix to make her feel better, to tell her she was “decent” and “made out of real gold,” and she began to cry. She cried and cried and did not stop. Joe says it was “extremely painful” to hear.

She was never prosecuted. In a deal with federal authorities, she agreed to a number of terms, including community service. She has said she began attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

She closed her charity but continued charity work. Today, she works primarily with Operation Smile, a group that repairs cleft palates and other facial deformities worldwide, and Halo Trust, a nonprofit that performs land-mine removal in countries affected by war. She is currently traveling in Rwanda with the One campaign, which raises awareness about AIDS and global poverty. She also became chairwoman of her dad’s company in 2000.

Cindy McCain’s friends say she has a kind of cautious radar for people. She seems to see her role as the protector of her husband and children. “She’s told me many times that she’s the only one he trusts implicitly,” Bayless says.

At a June town-hall meeting in Philadelphia, while the senator talks, the wife sits quietly. Afterward, several women from the audience are in a rapture over Cindy McCain. She seems so classy, they say, and her hair is beautiful, and she’s a mom with children in the service, and she understands sacrifice and worry. And this might sound sexist, says Valerie Gaydos, 40, a businesswoman from central Pennsylvania, but she likes the way Cindy McCain seems so traditional, seems to support her man and her man’s dreams.

“She’s flawless, flawless,” Gaydos says.