Sand Dunes

Published 4:00 am Friday, March 7, 2008

- Sand Dunes

The Christmas Valley Sand Dunes are a moving target.

If you went there in late March, which we did, and then planned a return visit in, say, a few thousand years, which we haven’t (something might come up), you might find they up and left. Blown away on the prevailing southwest wind.

Trending

True to form, a blustery breeze ruffled the ridges and sent extra-fine-gauge grit clicking into our pant legs. Bulletin colleague Andrew Moore and I were at the dunes because we’d heard they were out here and couldn’t quite figure out why. Plus, nearby Fort Rock is attractive this time of year if you like your weeds dried out and tumbling, your chicken broasted, piled with fries.

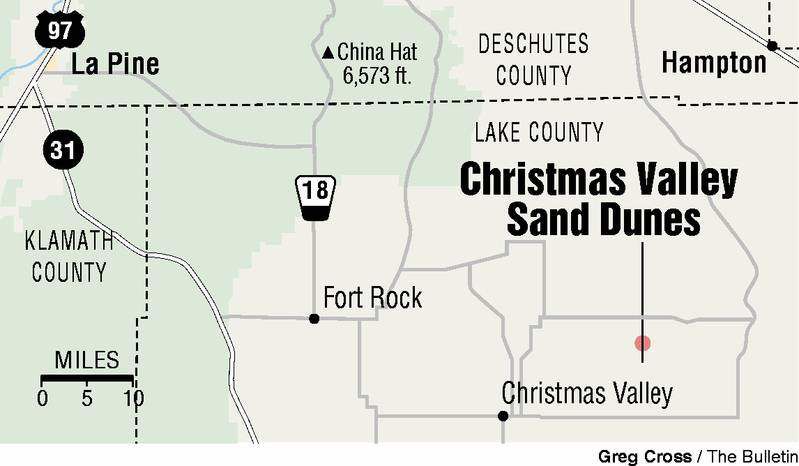

Sixteen miles outside the town of Christmas Valley, the sand dunes are the “largest inland shifting sand dune system in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest,” according to the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees this 11,000-acre geographic anomaly.

Like many BLM sites, there are no bathrooms, water, rangers, art galleries, fish cleaning stations or espresso stands out here. Just a few islands of squat, water-eschewing desert shrubs surrounded by acres of rippling round mounds of shifting sand, gently undulating to the horizon. And, during the warmer months, there are legions of off-highway vehicles, all glinting chrome, half-flat tires and throaty decibels tossing up rooster tales and etching their temporary signatures on the dunes.

We, however, found nothing but quiet. And despite the harsh realities of ever-present wind, sun and scant rainfall, the dunes offer a soft, pillowy, peaceful face to the world.

Caution: A walk on the dunes is an adventure in one-step-forward-half-step-back fitness.

The dunes are mostly pumice and ash from the eruption of Mount Mazama 7,000 years ago. A lot of it has blown in from adjacent Fossil Lake, an important paleontological site that dates back to the Pleistocene era.

Trending

And that sand appears to be headed northeast, where grow numerous ponderosa pine trees, far outside their comfort zone, miles from their accepted range.

The Lost Forest is just that, roughly 9,000 acres of pine in an area that’s all wrong for their survival. It’s the sand dunes that make all the difference. According to E.R. Jackman and R.A. Long in their regional classic, “The Oregon Desert,” the trees are part of a relic forest that dominated the High Desert at a time when massive lakes filled the basins. The drifting sand spread over a layer of compacted volcanic dust and acted as a mulch, which conserves precious moisture in an area of less than 10 inches annual rainfall.

“The water table in that area is quite high,” said Gretchen Burris of the BLM. “The ponderosa pines take advantage of that.”

What you see is a fairly typical area of mixed juniper and ponderosa congregated in a place 35 miles from the nearest pine forest. In the forest, vehicles are restricted to roads.

When in the area, a stop in Fort Rock is always on my agenda. And that always means a quick run through the store (there’s a new art gallery inside) and a more leisurely interlude at The Waterin’ Hole, the tiny burg’s unofficial city hall, town square and lunch counter extraordinaire.

From Bend, take U.S. Highway 97 south to state Highway 31, just south of La Pine. Head east on 31 through Silver Lake, then left at the Christmas Valley turnoff. Drive 14 miles to Christmas Valley, then turn right and go east on Christmas Valley Road for about eight miles. Turn north at the sign to the dunes and drive another eight miles. Turn right at the T and follow the gravel road east for about 10 miles. A high-clearance vehicle is recommended. Contact: BLM, 541-947-6239.

— Jim Witty