Safety concerns linger over camping and baby bottles

Published 5:00 am Thursday, March 20, 2008

- Safety concerns linger over camping and baby bottles

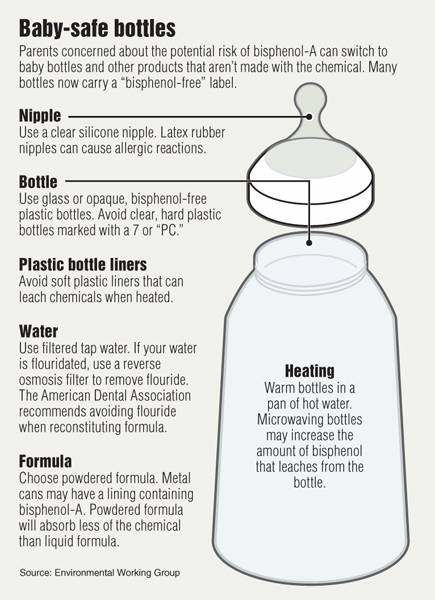

A pair of new studies released this year about the safety of clear polycarbonate plastic bottles has only served to further cloud the picture. The reports found that plastic baby bottles and the popular Nalgene brand water bottles can leach the chemical bisphenol-A when heated.

The findings renewed debate about the safety of the plastic bottles for both adults and children, but regulators and scientists have been unable to agree about the true risks involved. As the debate rages on in academic circles, many consumers are taking no chances, opting to err on the side of caution despite the inconvenience.

In January, researchers, led by University of Cincinnati pharmacology professor Scott Belcher, found that both new and used Nalgene water bottles released the chemical 55 times more rapidly when exposed to boiling water. Many hikers, climbers and backcountry skiers fill such bottles with boiling water during the winter to keep water from freezing.

“Inspired by questions from the climbing community, we went directly to tests based on how consumers use these plastic water bottles and showed that the only big difference in exposure levels revolved around liquid temperature,” Belcher said. “Bottles used for up to nine years released the same amount of BPA as new bottles.”

Belcher gathered used water bottles from members of a local climbing gym, then purchased new bottles from an outdoor store. The bottles were subjected to seven days of testing designed to simulate normal usage during backpacking, mountaineering and other outdoor activities.

When filled with water at room temperature, the bottles released the chemicals at a rate of 0.2 to 0.8 nanograms per hour. After the researchers poured boiling water into the bottles, rates of release increased to 8 to 32 nanograms per hour.

Then in February, dozens of environmental health organizations came together to release the Baby’s Toxic Bottle report, showing that plastic bottles made by Avent, Dr. Brown’s, Evenflo and Disney released 5 to 8 nanograms of bisphenol-A per milliliter of water when heated. The groups called for an immediate moratorium on the use of bisphenol-A in baby bottles.

The findings added to a long list of studies questioning the safety of the clear plastic. Previous research suggested the use of harsh detergents in cleaning plastic bottles could cause the chemical to leach. Last year, an Environment California Research and Policy Center report caused a stir, leading many parents to dump their plastic baby bottles and switch to glass.

Some outdoor stores, including Patagonia outlets and the Mountain Equipment Co-op chain in Canada, pulled all Nalgene products off their shelves pending a more definitive answer about the risks.

“Scientists are still trying to figure out how these endocrine disruptors … collectively impact human health,” Belcher said. “But a growing body of scientific evidence suggests it might be at the cost of your health.”

Risk or no risk?

Part of the reason for the controversy is that scientists can’t agree on how to establish the risk. Scientists have traditionally checked for toxicity by giving laboratory animals huge doses of the compound in question. If a toxic effect was found, they would test progressively lower doses until the effect went away. Then they could set a recommended exposure amount well below that level to provide a margin of safety.

Based on that methodology, the Environmental Protection Agency and the European Food Safety Authority have set the safe intake level at 50 micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s well above the amounts of bisphenol-A released in the Nalgene bottle and baby bottle studies.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, 93 percent of Americans have bisphenol-A in their urine. But the researchers said typical human intake of bisphenol-A was about 50 nanograms per kilogram of body weight. That’s one million times below the levels where no adverse effects were observed in animal studies.

Some bisphenol-A researchers, most notably University of Missouri professors Frederick vom Saal and Wade Welshons, have proposed that the chemical may have effects at lower doses that don’t appear with higher doses. If true, it would render the traditional methodology for establishing the toxicity of a substance obsolete.

It was vom Saal’s laboratory that conducted the research for the Baby’s Toxic Bottle report.

Controversy continues

The concept of a low-dose effect, however, is controversial and its applicability when moving from laboratory animals to humans, even more so. A number of studies with laboratory rats and mice found that exposure to low doses of bisphenol-A had hormone-like effects, impacting reproductive organs and immune function.

In January, the European Food Safety Authority rejected the low-dose argument, saying that findings in rodents could not be accurately applied to humans.

“New studies have shown significant differences between human and rodents, such as the fact that people metabolize and excrete BPA from their system far more quickly than rodents,” the agency said in a statement on BPA safety.

The Chapel Hill Bisphenol-A Expert Panel, consisting of 38 scientists including vom Saal, Walshon and Belcher, published a consensus statement last year supporting the notion of a low-dose effect of bisphenol-A. Those researchers concluded there was cause for concern but cited the need for further study on the true impact in humans.

“There is a large body of scientific evidence demonstrating the harmful effects of very small amounts of BPA in laboratory and small animal studies but little clinical evidence related to humans,” Belcher said. “There is a very strong suspicion in the scientific community, however, that this chemical has harmful effects.”

Plastics industry officials, however, complained that the panel was stacked with researchers supporting the low-dose hypothesis. They point instead to the findings of the National Toxicology Program’s Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction, which concluded there was a minimal risk of harm.

“These conclusions are from a very credible, highly qualified group of independent scientists with no conflicts of interest operating in an open and transparent review process,” said Steven Hentges, executive director of the Polycarbonate/BPA Global Group for the American Chemistry Council.

Their findings, he said, “provide strong reassurance to consumers that they are not at risk from use of products made from bisphenol-A.”

A bit of confusion

The debate has done little to relieve confusion for consumers. Each new report on baby bottles has spurred another wave of parents dumping their plastic bottles.

In some areas of the country, the popularity of glass baby bottles has cleared out store shelves. Some manufacturers have begun to label their plastic bottles made from other substances as BPA-free. Many outdoor enthusiasts have turned to metal water bottles or opaque plastic bottles that aren’t made from polycarbonate plastic.

Nicole Tucker, a midwife with Motherwise Community Birth Center in Bend, said many parents she talks to are not taking any chances — whether the plastic bottle is bisphenol-free or not — and are turning to the more expensive glass bottles their mothers once used.

“They believe it’s worth that extra investment. It’s not many more dollars to buy the Gerber glass bottles,” she said. “I think (BPA-free) sippy cups are where most people are finding difficulties. You just can’t find those in the grocery store.”

Some parents have found a middle ground, relying on plastic bottles and cups but limiting their exposure to hot water. “There are some people who use the plastic sippy cups who say, ‘I can’t deal with my car being sticky from juice boxes,’” Tucker said. “They use the plastic sippy cups, but they never put them in a dishwasher.”