Alzheimer’s doctors increasingly worried over younger Hispanics

Published 5:00 am Tuesday, October 21, 2008

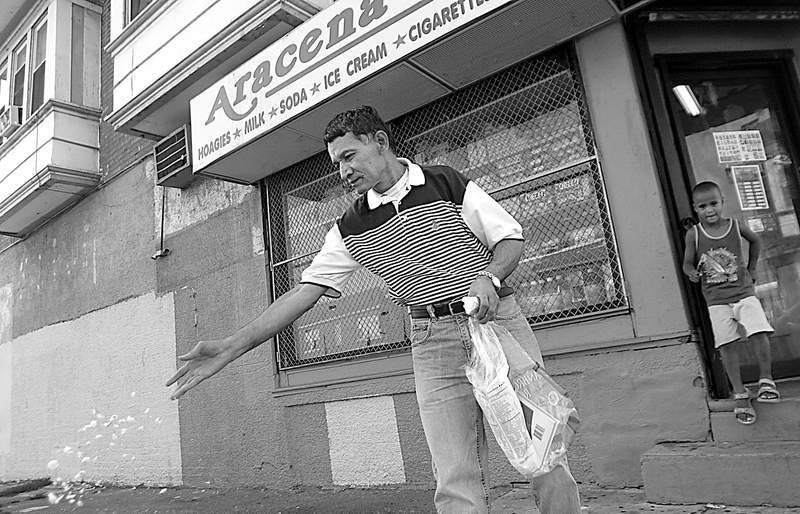

- Antonio Vasquez, 63, moved in with his daughter when he learned he had Alzheimer’s. He had lost his job at a bakery because he kept burning cookies, and he became lost going to job interviews. Scientists are trying to identify factors that may set Latinos apart when it comes to Alzheimer’s risks.

PHILADELPHIA — Antonio Vasquez was just 60 when Alzheimer’s disease derailed him.

He lost his job at a Queens, N.Y., bakery because he kept burning chocolate chip cookies, forgetting he had put them in the oven. Then he got lost going to job interviews, walking his neighborhood in circles.

Teresa Mojica, of Philadelphia, was 59 when she got Alzheimer’s, making her so argumentative and delusional that she sometimes hits her husband. And Ida Lawrence was 57 when she started misplacing things and making mistakes in her Boston dental school job.

Besides being young Alzheimer’s patients — most Americans who develop it are at least 65, and it becomes more common among people in their 70s or 80s — the three are Hispanic, a group that Alzheimer’s doctors are increasingly concerned about, and not just because it is the country’s largest, fastest-growing minority.

Risk factors

Studies suggest that many Hispanics may have more risk factors for developing dementia than other groups, and a significant number appear to be getting Alzheimer’s earlier. And surveys indicate that Latinos, less likely to see doctors because of financial and language barriers, more often mistake dementia symptoms for normal aging, delaying diagnosis.

“This is the tip of the iceberg of a huge public health challenge,” said Yanira Cruz, president of the National Hispanic Council on Aging. “We really need to do more research in this population to really understand why is it that we’re developing these conditions much earlier.”

It is not that Hispanics are more genetically predisposed to Alzheimer’s, say experts, who say the diversity of ethnicities that make up Hispanics or Latinos make a genetic explanation unlikely.

Rather, experts say several factors, many linked to low income or cultural dislocation, may put Hispanics at greater risk for dementia, including higher rates of diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, stroke and possibly hypertension.

Less education may make Hispanic immigrants more vulnerable to those medical conditions and to dementia itself, because, scientists say, education may increase the brain’s plasticity or ability to compensate for symptoms. And some researchers cite as risk factors stress from financial hardship or cultural adjustment.

The Alzheimer’s Association says that about 200,000 Latinos in the United States have Alzheimer’s, but that, by 2050, based on Census Bureau figures and a study of Alzheimer’s prevalence, the number could reach 1.3 million. (It predicts that the general population of Alzheimer’s patients will grow to 16 million in the same period, from 5 million now.)

“We are concerned that the Latino population may have the highest amount of risk factors and prevalence, in comparison to the other cultures,” said Maria Carrillo, the association’s director of medical and scientific relations.

The response

In response, Alzheimer’s and Hispanic organizations have started health fairs and support groups. Some Alzheimer’s centers have opened clinics in Latino neighborhoods.

“There’s some taboos” about Alzheimer’s, said Liany Arroyo, director of the Institute for Hispanic Health at the National Council of La Raza, which surveyed Latinos. “Folks did not necessarily understand what it was.”

Scientists are searching for what sets Latinos apart. Dr. Rafael Lantigua, a professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University Medical School, said, “There’s no gene at this point that we can say this is just for Latinos.” Lantigua added that one gene that increased Alzheimer’s risk was less prevalent in Latinos than non-Hispanic whites.

Kala Mehta, an assistant professor in the geriatrics division at the University of California, San Francisco, analyzed autopsies from 3,000 Alzheimer’s patients, finding “similar neuropathology” among Latinos, whites and African-Americans.

And Mary Sano, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, found that different ethnic groups shared behavioral symptoms, like repeating sentences and uncooperativeness.

But researchers say they have seen disparities in the timing of the illness and its severity when diagnosed.