Augusto Odone defied doctors for son Lorenzo

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 2, 2008

- Augusto Odone, right, made his mark with “Lorenzo’s Oil,” a compound that helped curtail his son’s disease. For more than a quarter century, he took pride in proving doctors wrong by enabling his son to survive adrenoleukodystrophy.

WASHINGTON — Shortly before his birthday in May, Lorenzo Odone — the inspiration for the 1992 movie “Lorenzo’s Oil” — came down with something. The objective sign that something was wrong came from the machines and monitors that surrounded his bed in suburban Fairfax, Va.

But Lorenzo’s father, Augusto, knew something was wrong even without the machines.

For nearly a quarter-century, Augusto had had his son fed through a tube. For more than 20 of those years, Lorenzo had not spoken a word. To casual visitors, Lorenzo seemed completely unresponsive, a victim of the terrible neurological disease that robbed him of his voice and hearing, and control over his body.

Augusto had watched over his son, first with his wife, Michaela, who died in 2000, and then on his own. Augusto had read thousands of stories to his boy, played hundreds of songs and stroked his hair in the long, dark hours before dawn. In the bond between father and son Augusto knew something was wrong. He debated whether to call an ambulance.

“I am very suspicious of doctors in general,” he said. “Every time we brought Lorenzo to a hospital, he would get so many other diseases.”

That thinking had characterized Augusto’s entire battle against his son’s disorder. For better and worse, the Odones had always marched to their own drummer. Call them stubborn, but if Lorenzo was still alive at 30, it was only because they had often rejected sober medical advice.

For two days and two nights, Augusto hovered by his son’s bedside, a 75-year-old man with serious medical problems of his own.

But Lorenzo’s vital signs deteriorated and Augusto finally called an ambulance. By the time it arrived, Lorenzo was dead. It was one day after his 30th birthday. The cause of death was ultimately not the neurological disease that had claimed so much of his life, but a lung infection, possibly caused by a stray food particle that entered his windpipe. Lorenzo died of aspiration pneumonia.

“I loved him so much, but at the end I screwed up, in the sense I didn’t call the ambulance in time,” Augusto Odone said, his voice breaking.

A long life

Friends and well-wishers urged Augusto not to beat up on himself: When Lorenzo was a boy, a neurologist predicted he would die within two years. That he had lived to 30 was an astounding achievement, the result of his parents’ determination. Whether Lorenzo was really able to hear and understand what was being said to him, for years the family had a former teacher of Lorenzo’s visit him every week to read aloud letters sent to him from children all over the world who had seen “Lorenzo’s Oil.” Whenever the weather allowed, Augusto would take Lorenzo out into the sunshine. Nurses attended to Lorenzo 24 hours a day. Augusto ministered to his son, taking as reward minute signs of brightness in his son’s eyes, or a flicker across his face.

Augusto’s actions stemmed from extraordinary love, but there was also something more.

For more than a quarter-century, Augusto has taken particular pride in proving doctors wrong.

Augusto came to Washington in 1969 to work for the World Bank. In 1978, he and his second wife, Michaela, had Lorenzo. One day, as Michaela read a story to her son, in bed with a cold, he said: “Mummy, I cannot hear you anymore. Can you raise your voice?”

Hearing specialists said nothing was wrong with his ears and referred him to a neurologist.

“He said, ‘I’m not sure’ — doctors are never sure — ‘but I just read an article about this very rare disease called ALD,’” Augusto recalled.

The neurologist suggested Hugo Moser, a neurologist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore who was studying adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a genetic disorder.

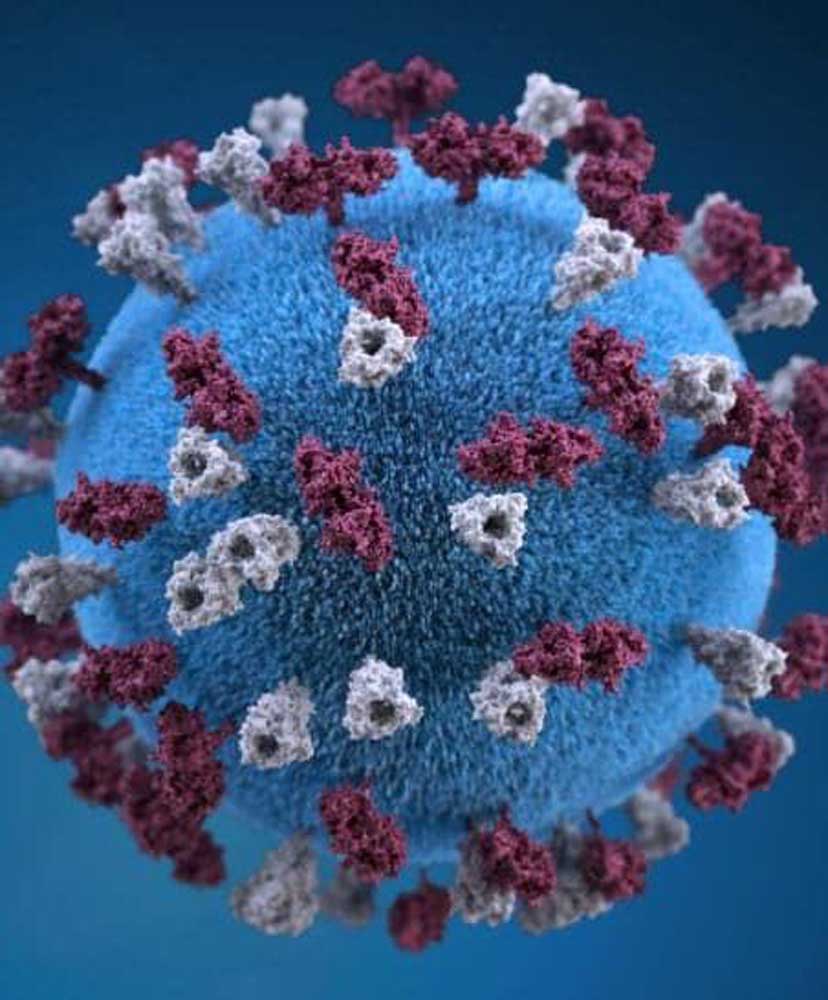

The blood test gave Augusto the empirical evidence he wanted: Lorenzo had ALD. The disease damages the myelin sheaths that house neurons, or nerve cells in the brain. This triggers an autoimmune response that eventually ravages the mind and body.

Augusto rebelled at the idea that complex science must be left to scientists; he began researching the disease himself. Poring over academic journals in the library in those pre-Internet days, Augusto studied some 200 articles

Augusto asked his wife’s sister to be his first guinea pig. She swallowed Augusto’s concoction — and lived.

Augusto began giving the concoction to his son. He kept meticulous records.

“One problem with medical research is that doctors think they know everything,” Augusto said. “In fact, they know very little, maybe only 5 percent.”

When Augusto took his results to Moser, the neurologist agreed to conduct a scientific test evaluating the effect of Lorenzo’s oil on boys known to be at high risk for ALD. He and his colleagues eventually showed that the treatment could freeze the disease in its tracks.