Students see their reflections in author’s pages

Published 5:00 am Sunday, October 5, 2008

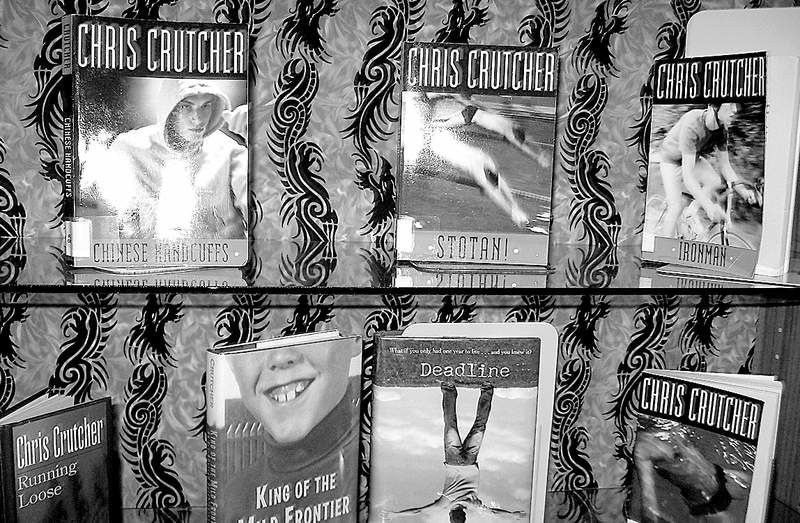

- Five of Chris Crutcher’s young-adult books were on an American Library Association list of the best books for young adults from 1966 to 2000.

STRASBURG, Va. — Here’s all you need to know about Chris Crutcher, whose young-adult fiction is set against a high school sports backdrop and is a hit with jocks and non-jocks alike, not to mention readers and supposed nonreaders:

During the morning sessions of an all-day appearance last week at Strasburg (Va.) High School, students approached Crutcher on three occasions and paused while tears welled in their eyes as they talked to him. That’s how much his books reflect their lives.

Although Crutcher, 62, has no children, he said that knack comes in part from years of working as a director of an alternative school and as a family therapist dealing with child abuse and neglect cases. And, as he says, “I can get back into my own adolescent head pretty quickly.”

He is listed eighth on the American Library Association’s list of most frequently challenged authors for 2007 — Mark Twain is third — for writing books with hard language and blunt themes such as abusive parents, molestation, racism, substance abuse, death, abortion and homosexuality.

His books are written in a descriptive, surprisingly funny and easily digestible style. Five of his works were on an ALA list of the best books for young adults from 1966 to 2000.

“Besides the Harry Potter books from when the kids are in younger grades,” said Katy Ferrell, who teaches a “reluctant readers” class at Strasburg, “I haven’t seen anything like this before.”

One could make the case that Crutcher has enhanced far more young lives sitting in Spokane, Wash., writing for strangers, than he did in years of working face-to-face with troubled kids. He said it’s a case of readers “bringing their own history to the story.”

“You feel like it’s about you,” said senior Cassandra Frye, a Virginia state discus champion, citing in particular Crutcher’s “Stotan,” about a swim team.

Junior Derek Buckley admitted he “wasn’t really into reading before this. But once I started reading these, I got into them. They’re really edgy. He tells a good story. You get attached to it.”

Crutcher, too, wasn’t really into reading when growing up in Cascade, Idaho, a splinter of a logging town. He would reword his older brother’s book reports to avoid reading the material himself. Not until he picked up Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” did he realize what he had been missing.

There are good guys and bad guys in Crutcher’s worlds, and a season or school year that provides a book-ended time frame. But his main objective is honesty. When he reached his 20s, Crutcher said, he realized his upbringing “sugarcoated” the world instead of preparing him for it. He wants young readers to be exposed to the kind of sticky life situations from which he was sheltered.

That sometimes gets him in trouble with censors, although a ban from adults is pretty much considered a seal of approval by young readers. In Strasburg, teacher Erin Hubbard’s English honors class, students read two of Crutcher’s books that were challenged or banned and then, in a series of projects, debated the merits of doing so.

All censorship does, Crutcher told the Strasburg students, is give adults and kids another reason to not talk to each other. He said he thinks identifying with one of his characters empowers readers and gives them the “insulation” they need to talk about their problems.

Crutcher likes to quote one of Pat Conroy’s lines from “The Prince of Tides”: “You can’t fix a broken childhood, but you can make the sucker float.”

“You’d get the argument all the time: Well, not all kids go through that,” Crutcher said about some of the wrenching lives his characters lead. “No, but all kids sit in a classroom with kids who have, and there’s a way to find compassion if you know what’s going on. If I know that that kid over there would rather show me his rage than his fear, then maybe I’ll have a little more compassion for his fear.”

Crutcher said he visits about 30 high schools a year and enjoys chatting with students. He said the talks help him keep his antennae up for teen dialogue. But when he gives talks at public libraries, he said, about 90 percent of his audience is adults who want to know where these stories were when they were kids, and who say they would have been helped by them.

“Boy, it takes them back,” Crutcher said. “High school is a pretty hard time. It’s developmentally a struggle. It’s meant to be.”