Too many shoulders to cry on

Published 5:00 am Saturday, May 3, 2008

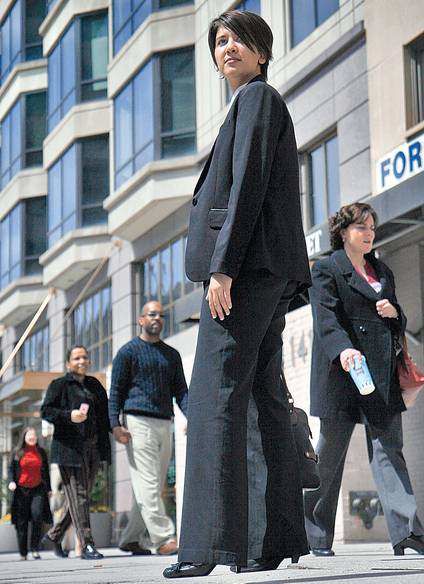

- Shadee Malaklou plans to trim the list of nearly 1,300 friends she accumulated on Facebook as an undergrad at Duke University. Never before has it been so easy to keep up with so many people with whom you otherwise would have lost contact.

WASHINGTON — Shadee Malaklou has lots of friends. A whole lot — 1,295, according to her latest Facebook count. But whom exactly can she count on?

Malaklou, 22, acknowledges that if she ran into some of her “friends” on the street, she might not remember their names. When she went to Duke, where “I was quote unquote popular,” social life was so competitive that sometimes invitations were based only on online determinations of how hot a person was, and whether her “friends” were cool.

Now that she is working at a Washington nonprofit, Malaklou is planning on pruning her “friends” as a rite of spring cleaning, defriending people who have come to mean little to her.

She does stay Facebook friends, however, with professors who might be good for letters of recommendation to graduate school.

“The biggest value-added is that it helps maintain relationships — somewhat superficial but not worth getting rid of,” she says.

The word “friend” has long covered a broad range of relationships — roommates, Army buddies, pals from the last law firm, old neighbors, teammates, people you used to smoke dope with in back of your high school, people you see once a year at the Gold Cup, scuba instructors and carpool members, along with fellow gun collectors, Britney fans and cancer victims. The Oxford English Dictionary traces “freondum” back to “Beowulf” in 1018, and “to be frended” to 1387.

But MySpace and all the hundreds of other social networking Web sites, including Flickr and Twitter and Bebo, have caused us to think afresh about the boundaries and intensities of these relationships.

Never before in history has it been so easy to keep up with so many people with whom you otherwise would have lost contact. These new electronic meshes are more than mere improvements over alumni magazines, holiday cards with pictures of families and those horrible letters about their lives, Rolodexes, yearbooks, organizational newsletters, and birth and death notices in the newspaper.

Summer friendships, for example, have been transformed. The ritual of meeting again at the beach after a long winter was once marked by hours of catching up. Not today. Networked people who haven’t seen each other in forever already know about the new boyfriend, and what happened to the old one — in very great detail. They also know about the old school and the new job. They have known, every day, no matter where in the world they roamed, the instant that emotional change occurred. Now, after the initial squeals and swaying hugs, conversations pick up in mid-sentence. It’s a mind-meld uncanny to watch.

This is a world of “participatory surveillance,” says Anders Albrechtslund, of Denmark’s Aalborg University, in the online journal First Monday.

Real online friends watch over each other — mutually, voluntarily and enthusiastically, in ways that can be endearing.

Others have referred to it as “empowering exhibitionism,” Albrechtslund says.

Call it Friends Next.

You can pick your friends, but …

Life was once so simple. “I’ll be there for you, when the rain starts to pour,” went the “Friends” theme. “I’ll be there for you, ’cause you’re there for me, too.”

Today, when you join a social network, the first thing you start questioning is if you really want to embrace every “friend” request. Such promiscuity’s downside quickly becomes obvious. Do you really want every petitioner — no matter how unclear his identity or intent — to see your revealing personal information? Much less those pictures of Ashley, Courtney and Jason from last Saturday night?

There’s this girl at school “who won’t even say ‘hi’ in the hallway,” says a 16-year-old junior at a Washington, D.C., high school who desires anonymity for fear of social ostracism. The aloof girl keeps asking to be a virtual “friend” on Facebook, arguably the most sophisticated popular site, no matter how often the answer is no.

This junior struggles with the relationship dilemma. “Why would I want to be ‘friends’ with this person? I occasionally smile at her. I guess it’s kind of really impersonal to me, if she’s not even going to say ‘hi.’” The high-schooler says she’s “selective in acceptance of friends” — she has “only” 131 on Facebook. But if she had a relationship blow up, on the shoulders of how many could she cry?

“Probably like 20,” she says.

For two decades, online social networks have been touted as one of the finest flowerings of our new era. But what is the strength of ties so weak as to barely exist? Who will lend you lunch money? Who will bail you out of jail? Who’s got your back?

A remote Wyoming cattle ranch was home to Internet pioneer John Perry Barlow when he was a boy in the ’50s. In the ’80s, when he encountered the first settlers of online communities such as the Well, he felt like he was back in the small towns he once knew. He reveled in the throngs “gossiping, complaining … comforting and harassing each other, bartering, engaging in religion … beginning and ending love affairs, praying for one another’s sick kids,” he once wrote. “There was, it seemed, about everything one might find going on in a small town, save dragging Main or making out on the back roads.”

He has since developed a more jaundiced view of the Internet’s utopian promise to dissolve barriers between people — “the reason I got involved in that stuff” in the first place, he says.

Barlow hoped for “a distinctly 19th-century understanding of what community was. Where it was not just bail you out of jail, but stand behind you with a loaded gun — the Wyoming version.” Instead, he sees people collecting and displaying enormous numbers of “friends” on MySpace, “for the same reason that elk grow antlers, I expect.”

Some encounters can be novel and strange. Jessica Smith, 23, remembers the time someone she’d never heard of from Vassar tried to friend her. It happened when Smith was an undergraduate at George Washington University and had just started dating her boyfriend, Peter. Turned out, the stranger was Peter’s ex.

“There was nothing friendly about this,” she says. “She only wanted to know about me.” When Smith didn’t fall for this probe — like it was the ex’s business how cute she might be, or clever — “a friend of hers friended me. Like that would trick me — ‘Ooo, a new friend from Vassar!’ It was weird. Really creepy.” Before social networks, “she wouldn’t have called me or written me a letter.”

Stitched together

We’re inventing Friends Next every day.

“For most people, when they thought of their close friends, it was people with whom they would share personal things,” says Sherry Turkle, a sociologist and psychologist at MIT who has studied online social networks from their beginnings. “What’s changing now is that people who are not in the other person’s physical life meet in this very new kind of space. It is leaving room for new hybrid forms.”

The weirdness of Friends Next is that it comes at you like a melodrama: “Is he married yet?” “Is he still straight?” “She’s changed her religious views to ‘rain dancing’? I thought she had a cross tattooed on her hip.”

“Facebook is more about entertainment than work,” says Nicholas Christakis, a physician and sociologist who studies social networks at Harvard. “Instead of watching soap operas, they’re watching soap operas of people they sort of know.”

“It sucks you in,” says Mary Washington’s Clark. “The public conversations — it’s digital eavesdropping.”

Losing friends in this new world is as fraught as making them. “Real world friendships are not usually intentionally ended,” says Rebecca Adams, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. “Folks just let things naturally cool off. On Facebook, decisive action has to be taken.” Defriending cements that a friendship is over.

The best soap operas occur when a couple breaks up. Change your profile from “In a Relationship” to “Single” — or even more ominously, “It’s Complicated” — and little press releases blast out to all your gossip-hound “friends.” Massive e-mailing and tongue-wagging ensues.

It’s futile to try to erase latent traces of Friends Next. “The digital trails of an online friendship — true or not — really do last forever,” Albrechtslund says. Its evidence is stored on servers indefinitely, beyond the control of the persons involved.

The real thing

So in Friends Next, what matters? Is being good company enough? Is trust a key ingredient? Or loyalty? Or self-sacrifice?

“Go through your phone book, call people and ask them to drive you to the airport,” Jay Leno once said. “The ones who will drive you are your true friends. The rest aren’t bad people; they’re just acquaintances.”

“It’s the friends you can call up at 4 a.m. that matter,” said Marlene Dietrich.

While Facebook will allow you as many as 5,000 “friends,” enduring realities impose far more significant limits.

No matter how thick your soup of constant communication, sooner or later you may have to decide who will be your bridesmaid.

No matter how easily you can get Facebook on your iPhone, sooner or later, you may have to decide who will be the godfather of your child.

And no matter how extensive your profile, it is certain that someday, someone is going to have to decide who will be your pallbearers.

Worlds colliding

You know all those separate lives you lead? When you’re not being the FTC lawyer or the hair-metal band freak, you’re the wife of a glassblower and mother of two who likes to spend every vacation she can on the black-sand beaches of Dominica?

Forget about keeping those lives neatly partitioned in Friends Next.

“It’s the post-modern nightmare — to have all of your selves collide,” says Rebecca Adams, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, who edits Personal Relationships, the journal of the International Association for Relationship Research.

In villages of the agrarian age, you wouldn’t even have developed those various personalities. In Friends Next, you can’t escape them. “If you really welcome all of your friends from all of the different aspects of your life and they interact with each other and communicate in ways that everyone can read,” Adams says, “you get held accountable for the person you are in all of these groups, instead of just one of them.”

This became clear in 2003, on an early site called Friendster. Two 16-year-old students approached a young San Francisco teacher with two questions: Why do you do drugs, and why are you friends with pedophiles? So reports danah boyd, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California at Berkeley who has become renowned for her research into online social networks, and who insists on rendering her name without capital letters.

The teacher’s profile was nothing extraordinary or controversial. Her picture showed her hiking. But she had a lot of friends who were devotees of Burning Man — the annual weeklong festival in the Nevada desert that attracts tens of thousands of people experimenting with community, artwork, self-expression, self-reliance, absurdity and clothing-optional revelry.

“The drug reference came not from her profile but from those of her friends, some of whom had signaled drug use (and attendance at Burning Man, which for the students amounted to the same thing),” boyd writes. “Friends also brought her the pedophilia connection — in this case via the profile of a male friend who, for his part, had included an in-joke involving a self-portrait in a Catholic schoolgirl outfit and testimonials about his love of young girls. The students were not in on this joke.”

In Friends Next, all your lives and circles of relationships are collapsed. Extreme cases of friend mash-ups resemble the barroom scene in “Star Wars.”

— By Joel Garreau