A Bend man has a place in history COVO: Helping ‘where others have failed’ A lifelong desire to help

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 13, 2008

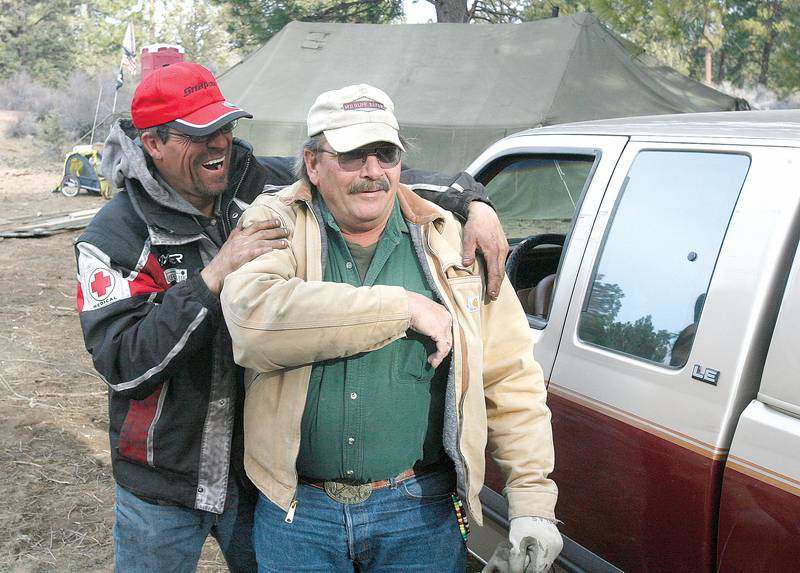

- Jeffrey St. Clair hugs Jim Gunn, co-founder of Central Oregon Veteran’s Outreach. Gunn was at a homeless camp recently to help clean up trash left over from the winter. Gunn has stepped down from his post at COVO, though he says he’ll return.

Jim Gunn drove his 1989 Ford Ranger into sparse woods near Bend last week.

Homeless men walked out of the woods as Gunn stepped out. He and a half-dozen men immediately started into the day’s work — cleaning the camp of trash.

Trending

Gunn, 57, was at the camp to help the men fulfill a promise to the property owner to keep the land clean. After throwing a few more items — a box springs ravaged by dogs, bags of trash — into a trailer that Gunn dropped off earlier, he hitched the load to his truck and drove to a local dump.

Gunn is the outreach director and co-founder of Central Oregon Veteran’s Outreach. For the last four years, he’s visited homeless camps — about 50 of them — around Bend. Some say he is the only man who can walk into any camp and immediately be trusted. The men and women in the camps count on him and the people Gunn brings to help them survive harsh conditions like this past winter.

“He saves lives,” said Mike Marshall Sr., 56, an Army vet who lives in the camp. “He saves lives, brings wood, food. We’ve managed to stay alive because of him.”

Gunn helps, in part, to pay back veterans groups like the Veterans of Foreign Wars for support he’s received from them, he said. He lives on the fixed income of a pension from his days in the Marines.

This past winter, though, got to Gunn, and he recently decided to step down from COVO. In one particularly gruesome incident, Gunn found a homeless man who was so sick, he’d been unable to leave his tent for days, even to go to the bathroom. Frostbitten, shot-through with gangrene and near death, the man was airlifted out of the camp. His legs were amputated at the knee.

“I guess I took the casualties this winter harder than I thought,” said Gunn, one day after he took an indefinite leave of absence from COVO.

Trending

Everyone at COVO thought Gunn needed a break, some time to ride horses, to be at home. Gunn hasn’t taken a break since he helped establish COVO in 2004, said Stu Steinberg, the group’s operations director.

Gunn would do things many would never do, Steinberg said.

“He got a call at midnight; guys say there’s some homeless chick that needs help,” he said. “Jim goes and gets her shelter, and she wasn’t even a vet.”

The camps

The camp Gunn visited last week must be hidden from view of nearby roads and homes, according to a new set of rules posted around the camp. A permanently parked RV is draped with a camouflage net.

It can take time to see the better-hidden tents and lean-tos among the trees, like eyes adjusting to the dark.

Gunn can, apparently, see in the dark.

“It’s gotten so I can see a tent a mile away in the woods,” he said.

Gunn seems to dominate whatever space he is in, but always quietly. At the COVO office, he sat behind a desk and flipped through mail. The envelopes were puny in his hands — scraped and rough — and he flipped back and forth between the bills. The baseball cap on his head doesn’t quite cover his graying hair.

“You know Babe the Blue Ox and Paul Bunyan?” asked Marshall, the vet. “That’s what he looks like, Paul Bunyan.”

When working outside with the homeless, he’s dressed in layers — flannel, T-shirt, vest, Carhart jacket — and he jokes easily with the homeless men in camps. He pats them on the back and asks each one, “Hey, man, how you doing?”

When he’s inside, at the office, he spoke quickly and jumped from topic to topic, as if in rush to get past pleasantries and back outside.

Gunn, a veteran who returned from Vietnam in late 1968, began trying to help homeless vets about four years ago. He and Kerry, who would become his wife, saw too many men on the side of the road, begging for money and food. Gunn began to give them money and ask them to talk with him, to explain how they ended up homeless.

“Homeless veterans are the great moral outrage of this country,” said Gunn.

He admitted paying for the conversations was a mistake, but those discussions showed him the way into the area’s camps. He began devoting his mornings, his days and his nights — about 50 hours each week — to helping the homeless vets. Colleagues estimate Gunn worked much more than that.

He began to visit the camps spread around Central Oregon and realized that he couldn’t walk away from any homeless people. He had to attend to their needs.

Jacob Calhoun, 24, who has lived at a camp for more than a year, remembered meeting Gunn while sleeping outside along a rocky outcropping somewhere near town.

Gunn introduced himself as being from COVO.

“I’m not a vet,” said Calhoun, when another of the men in his group who was a vet got food from the back of Gunn’s van.

“I don’t care,” snapped Gunn. “Get to the back of that van.”

Calhoun ate that day and now lives in a camp that Gunn helped him find.

Early on

Gunn’s maternal uncle was Wilson Rawls, the author of the famed children’s book, “Where the Red Fern Grows.” Rawls would often fly into Los Angeles for a reading or movie event when Gunn was growing up, but he never called on his sister — Gunn’s mother, Patricia — who held her brother in the highest esteem.

Each time that his mother found out, she cried. Her favorite brother had ignored her.

When Gunn was about 15 years old, living with his family in a remote section of the Mojave Desert in California, he decided he’d seen his mother cry enough. He wrote a letter to Uncle Doc Rawls.

“I wrote, ‘That’s the last time you make my momma cry. If you do that again, I will hunt you down,’” remembered Gunn.

A few months later, out of the brown desert landscape, a stretch limousine emerged. The driver stepped out and grandly announced that, “Mr. Wilson Rawls requests the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Gunn in Los Angeles.”

“That limo drove them to Los Angeles, and they spent time with Doc. Then it drove them the 250 miles back,” said Gunn, and he laughed.

The fight

Gunn’s colleagues around Central Oregon all speak of his devotion to fighting homelessness. He doesn’t do it with politics, a game he is not gifted at. When asked about his rank in the Marines, he replied, with as mischievous a laugh as he could muster, “When? It sort of went up and down.”

Gunn just arrives and works.

“(Jim) is the driver behind getting out to the camps and doing direct service to the homeless,” said Taffy Gleason, executive director of Bend’s Community Center. “He has saved the lives of at least a half-dozen people that would’ve died in those camps.”

He drives his own truck around the region, into the camps where not many people can or will go. The truck doesn’t always make it along the roads leading to the camps. Gunn ends up spending much of his own money on his work, said Corky Senecal, housing and emergency services manager at NeighborImpact.

“I’ve heard about how, in the winter, it’ll break down, and he’ll just crawl under the truck, in the snow, and start fixing it,” said Senecal.

The truck does hard service at Gunn’s hands. When the snow finally melted, he used it to try and grade the dirt lanes at one camp into something closer to roads.

Kerry Calhoun, 54, Jacob Calhoun’s father, spoke of a teeth-jarring experience holding onto the back of Gunn’s pickup, and standing on a sort of heavy rake as the trail became a road. The truck bounced and was jolted around the path — sometimes by ruts more than a foot deep.

“What that man wants, I give him,” said Calhoun.

Vets

Gunn and COVO are devoted to helping vets find health care, shelter, food and peace. When Gunn came back from Vietnam, he was homeless, wandering the country for three years living out of a van. His work now, he said, is devoted to making sure veterans aren’t left wandering.

Gunn became visibly frustrated when he spoke of the veterans coming home now. He’s already seen young veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars living alone in camps around Bend. Sitting in his truck, he gripped the steering wheel so hard that the vinyl squeaked.

“There are a lot of vets coming back to nothing,” he said between pauses and stares out at the homeless camp. “They’re still back in the desert in their mind and don’t feel like they belong to society.”

Eventually, Gunn moved with his former wife, Marie, to Crooked River Ranch in 2000. The couple raised paint horses. One day, Marie went on a ride. “And she didn’t come back,” said Gunn.

The horse Marie was riding bucked her off, then kicked her in the back of her head, crushing her skull. She was on life support for three day at St. Charles Bend.

“It was the worst three days of my life,” said Gunn.

At the end of those days, Gunn decided that it was time to have her doctors take her off life support. The representative at the hospital kept asking Gunn if he wanted to do it.

“You have to say, ‘Yes,’” said Gunn. “But I had a knot in my throat the size of a softball.”

Gunn could only nod. Eventually, the hospital representative said, “He said, ‘OK.’”

Seeing his depression, a few of Gunn’s neighbors broke into his house and took away his guns. He returned home, alone, and found a note from them.

The neighbors were worried that Gunn would turn a weapon on himself. “I appreciated it later,” he said. “At least they left a note.”

Gunn kept going to group sessions run by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Marie had “dragged” Gunn to his first meetings, which were designed to help vets with postraumatic stress disorder. But the meetings became Gunn’s brace after her death.

“They saved my life,” said Gunn, bluntly as always. Part of his work now, he said, is trying to pay back other vets for the help he received.

Gunn is married now to Kerry, and when he speaks on the phone with her — often from somewhere out in what passes for Central Oregon’s bush country — his voice softens.

The couple met while they were both working on a road construction crew and have been together for the last three years.

“She was the first heavy machine operator that I kissed and liked it,” said Gunn.

Rest

Gunn is not sure when he’ll start going to the camps again, though he’s sure that he will. But he hasn’t taken a break for four years, and he decided he needed the rest.

“I just got to get things together,” said Gunn.

Marshall, one of the homeless vets living in the camps around Bend, credited Gunn with bringing more help to camps. Others credit Gunn with opening the door to the camps, which can be full of people wary of the world outside their tents.

“Most importantly, he comes to us as a friend,” said Marshall. “He shows us people are out there who care.”

The Central Oregon Veteran’s Outreach program works with veterans in multiple ways.

Its members work on outreach, trying to find veterans in homeless camps.

“We’re able to help where others have failed,” said Stu Steinberg, operations director. He helps vets find benefits they are entitled to, or have been entitled to, for sometimes decades.

Steinberg estimates COVO has helped 12 veterans receive $379,000 in benefits in 2008’s first three months.

The program also runs a transitional home designed to gradually move veterans from the street to independent living.

COVO began in 2004 at a Vietnam Veterans of America meeting. Steinberg remembers Jim Gunn, the local chapter’s vice president, walking into the meeting and asking, “What the hell are we doing about the homeless vets?”

The group began to understand that part of its mission was to teach people what veterans need. At a public meeting about a proposed transitional home, Steinberg realized that not everyone understood what help veterans needed.

“A woman stood up and said, ‘I have supported the troops, and I’ve taken doughnuts to them,’” said Steinberg.

“I stood up and said, ‘So what. If you support vets, really support vets, we don’t need doughnuts. We need housing and sleeping bags.”

COVO’s “Home of the Brave” transitional housing has run on donations and a patchwork of grants. The group’s leaders hope a recent grant application will be approved. It would pay for all operation and mortgage costs. It would also free up money, Steinberg hopes, to hire a full-time case worker who would help the veterans stay on their rehabilitation plans.

He also said that COVO might be able to start funding coursework for veterans in the transitional housing program.

“I like to say, ‘We can do this,’” said Steinberg of helping homeless vets. “But it hurts; it hurts.”

— Patrick Cliff