CEC debts rise while upkeep costs lag

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 8, 2007

- CEC debts rise while upkeep costs lag

Redmond-based Central Electric Cooperative saw $6.2 million vanish overnight last month, when it restated its 2005 earnings from a $600,000 gain to a $5.6 million loss.

The announcement was the latest change for a company that fired three top officials in the last year and watched its debt grow by a third since 2001.

State records also show the cooperative spent the least on system maintenance per customer of any cooperative in Oregon and saw its inspection program deemed unacceptable by the state in two straight audits.

Neither current CEO Dave Markham nor any of the current board members responded to repeated questions about the company’s finances, subsidiaries or the firings – although in an e-mail passed along by Member Services Director Jim Crowell, Markham pointed to National Rural Utilities Cooperative Finance Corporation records that CEC ranked in the top 14 percent for fewest outages among cooperatives nationwide.

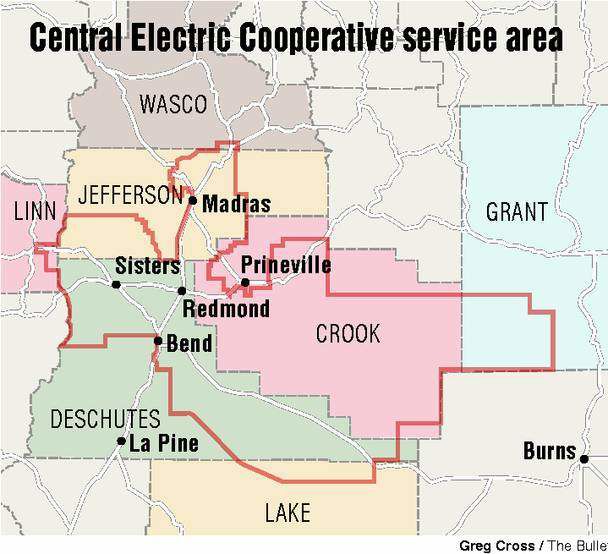

The news comes during a time of rapid growth for Central Oregon’s second-largest electric utility. The cooperative has seen its membership increase by nearly a third over the past decade and is poised to see more growth in the form of high-priced resorts such as Brasada Ranch in Powell Butte. The member-owned cooperative – operating much like a nonprofit company – powers more than 30,000 homes and businesses in some of Central Oregon’s fastest-growing cities. The co-op’s service area stretches from the north side of Bend to Madras, where it powers the new Deer Ridge Correctional Institution, east past Prineville into Grant County and west through Sisters and Hoodoo Mountain Resort.

Crowell directed questions about the earnings adjustment to former CEO Al Gonzalez, who did not reply to five telephone requests for comment left over three weeks.

But at the company’s annual meeting March 9, Gonzalez dismissed the earnings restatement as a ”book entry.” According to Gonzalez, the assets of an Internet company CEC started in 2001 and then dissolved in 2005 were worth much less than CEC’s officers originally believed.

”That is not cash, that is a book entry,” Gonzalez said, of the loss of value. Gonzalez retired as CEO last year and now works as the company’s power supply manager.

But just because the loss was on paper doesn’t mean it won’t cost the company, said CEC member Shane Morgan, who unsuccessfully ran for the company’s board of directors last month. Morgan said he ran for the board after seeing the company’s debt increase and other financial indicators worsen over the past few years.

”Sure it’s a book loss, but it shows you’ve got some serious depreciation on your assets,” said Morgan, a Prineville accountant. ”It just leaves more questions.”

Such as, why did a power cooperative take the risky move of starting an Internet business in the first place?

”I don’t know enough about all of it to say if it’s good or bad,” Morgan said. ”But why are we in subsidiaries and is that the right thing for the co-op to be doing? Typically that’s left for investors who have substantial capital.”

Former CEC Line Supervisor Bob Hoar, who oversaw construction and maintenance, told The Bulletin the company hasn’t spent enough money upgrading its system. While the company’s outage rates have been lower than the national average since at least 2004, a maintenance backlog could create bigger problems in the future, including more outages or higher rates, said Hoar, who spent 27 years at the company.

”If the subsidiaries are not successful, if they can’t make good on their loans or guarantees, the net effect may increase fees to CEC’s customers,” Hoar said.

‘An opportunity’

While company officials would not answer questions about their subsidiaries, Gonzalez explained his business plan to a few hundred members at a meeting in March.

CEC, Gonzalez said, wanted a new source of income to offset rate hikes set to begin in 2011 from the federal Bonneville Power Administration, which provides most of CEC’s power. Bonneville plans to introduce a tiered rate structure, according to an agency spokesman, which will limit the amount of low-cost power available to utilities like CEC. Gonzalez estimated the change in rate structure could cost the cooperative about $3 million each year in higher rates.

Rather than increasing the rates of CEC members, the answer, then-CEO Gonzalez decided, was to diversify.

In 2001, CEC made its first foray outside its core power transmission business. The company bought a $50,000 fuel cell from IdaTech, with help from a $25,000 grant from the Bonneville Power Administration. The cells could save the company the cost and trouble of maintaining power lines to distant parts of its service area, he said.

”The idea was if we had somebody way up the river, instead of maintaining power lines for mile after mile after mile, maybe we could place a distributed generation fuel cell there and serve four or five members there,” Gonzalez said.

Many of the high-tech generators were fueled by propane so, Gonzalez said, the company decided to get into that business as well, to insulate itself against propane price spikes.

”We thought they’ll run the price up,” Gonzalez said. ”The board felt it was important to be in the propane business.”

That company, CoEnergy, distributes propane in Central Oregon and the Willamette Valley, according to Gonzalez and the company’s Web site. According to Gonzalez, that company is in the black now, five years after it was founded.

”That’s a success story for us,” he said.The Bulletin could not verify his statements about the subsidiaries, which are private.

CEC continued to launch new ventures that year, starting a long-haul broadband Internet company, called NoaNet of Oregon, and a local Internet provider, Quantum Communications.

In 2005, CEC dissolved NoaNet, which was originally launched as a nonprofit. Gonzalez blamed the company’s failure on slow decision making and said for-profit firms discriminated against it.

”They said we’re for-profit companies, we don’t know what a cooperative is,” Gonzalez said. ”We don’t know you, we don’t like you, we don’t trust you.”

NoaNet was reincarnated as the for-profit LS Networks, but neither that company nor Quantum Communications is profitable, Gonzalez said.

In all, Central Electric has borrowed about $16 million to start its three subsidiaries and spent $1.5 million more to pay interest on that debt, he said. In comparison, the company earned $39.7 million in revenues in 2006. CEC’s long-term debt has increased by 35 percent since 2001, according to CEC’s annual reports, to about $73 million.

It was unclear from Gonzalez’s speech whether those figures represented CEC’s total spending and liabilities in relation to the subsidiaries. When asked, Crowell told The Bulletin that Gonzalez, who still oversees the subsidiaries, was the only person who could answer those questions. When asked how to reach Gonzalez on March 12, Crowell responded with the following e-mail:

”If Al’s number is not in the phone book (I don’t have one of the newer ones), then I can’t help you. We have an iron-clad rule against giving out the home phone number or home address of ANY employee. A utility in Philadelphia did one time and the person who obtained the address went over to the residence and killed five people.”

The Bulletin did not ask for Gonzalez’s home address or phone number. After The Bulletin asked again to speak with Gonzalez, Crowell, again answered by e-mail:

”The only way I know that Al can be reached is to call the general number, 389-1980. A customer service representative will then plug you in to either him or his secretary/assistant.”

Gonzalez earned $35,000 in 2005, in addition to his $306,000 salary, to oversee the subsidiaries, according to the company’s tax return for that year. CEC’s 2006 return was unavailable, Crowell said.

Not keeping up

The cooperative’s increasing debt hasn’t come at the expense of the company’s core operations, CEO Markham said, at the company’s annual meeting.

”Since starting the (subsidiaries) we have invested more than $78 million in construction, upgrade and maintenance of the electric system,” Markham said.

But a former employee who oversaw the company’s maintenance disputed the assertion that CEC has spent enough money maintaining the system. Line Supervisor Hoar left the company in January, after 27 years. The company declined to comment on why Hoar left, but a letter from CEC provided by Hoar says he was fired for job performance ”that has fallen far below that which is expected at CEC.”

Hoar maintains he was terminated because he demanded that CEC increase its maintenance budget. He has a labor complaint pending with the state Bureau of Labor and Industries. Since last summer, the company’s CFO, Bob Bingham, and its longest-tenured lineman, Paul Yancey, also left the company. Both told The Bulletin they were fired.

”I voiced my concern that CEC’s investment into operations and maintenance was being compromised by our ongoing investments into the subsidiary companies,” Hoar said. ”All of us that had our hands on that electrical system every day were concerned that we were not keeping up with the infrastructure of CEC.”

Markham did not respond to requests to detail how the $78 million in ”construction, upgrade and maintenance” was spent. When asked, Crowell responded by e-mail.

”In regard to your call yesterday about his annual meeting message to the membership, I asked him about that and he has e-mailed me the text of the quote you alluded to yesterday,” Crowell wrote. ”It reads: ‘Since starting the subsidiaries, we have invested more than $78 million on construction, upgrades, and maintenance of the electric system.’”

When The Bulletin again asked Crowell to break down the $78 million by year, category or project, he wrote that the money ”would cover new lines/poles, etc. needed to serve new accounts; upgrading of existing lines/poles, etc. to serve both new and old accounts, and maintenance of the full gamut of equipment across the entire system.”

Last summer, three current and former CEC employees sent an anonymous letter to CEC’s board of directors, voicing similar concerns about the company’s maintenance spending and the financial impact of its subsidiaries. Hoar was not one of those employees.

In an Aug. 1, 2006, letter to CEC Attorney Martin Hansen and board members, the employees’ attorney, Roxanne Farra, wrote that they were concerned CEC wasn’t allocating ”adequate funding for system upkeep/maintenance … to replace old and worn equipment; and recruit and retain qualified personnel.”

CEC and Gonzalez responded by suing the then-anonymous employees for defamation. After a judge ordered Farra to name her clients, CEC dropped the other defendants and focused a $600,000 lawsuit on former operations manager Jeff Spencer. Spencer told The Bulletin he was fired in November, but declined multiple requests to comment on the letter or lawsuit.

Caution

While CEC officials say its system is in good condition, a state safety audit found the company’s inspection program ”unacceptable.” The most recent safety audit by the state Public Utilities Commission found 49 mostly minor violations in the CEC’s lines near Alfalfa, but state officials issued a ”caution” notice to the company’s inspection program for failing to identify such a large number of violations.

”The detailed Facility Inspection performed in the identified areas failed to identify a significant number of (safety) violations, in a wide variety of categories,” the report issued Feb 27 reads. ”Given the fact that CEC had inspected this area relatively recently, the number of (safety) violations remaining is unacceptable.”

A 2005 safety audit did not include a caution notice, but inspectors made the same judgment that the number of violations – more than 60 – was ”unacceptable.” The state does not regulate the finances of electric cooperatives, according to a PUC spokesman.

Crowell did not respond to questions about the company’s inspection program. But in an e-mail, Crowell wrote that the majority of 49 safety violations found by state inspectors were minor – and weren’t the company’s fault.

”Almost all of these citations deal with clearance or attachment issues by local communication companies (telephone, cable) which are allowed, by Oregon statute, to affix their lines to our poles,” Crowell wrote. ”We have ongoing suits against some of these companies for unauthorized placement of their lines without proper notification and/or fee payments to us for the use of our poles.

Last year, CEC spent $10,560 less on maintenance than it did in 1997, state Public Utility Commission records show. CEC spent $1,784,071 on maintenance in 1997, compared to $1,773,511 last year according to the company’s annual reports.

While the company’s spending declined, over that time costs for electrical materials have skyrocketed, Markham said, in his annual meeting speech.

State records for 2005, the most recent year available, show that CEC spent the least, by far, on maintenance per account than any of the state’s electric co-ops. The company spent $61.53 on maintenance for each of its 28,293 members that year. The next lowest cooperative, Salem Electric, spent $102.27 per member. The state average was $203 per account, more than three times what CEC spent.

Bill Kopacz, general manager of Midstate Electric Cooperative, based in La Pine, said his company spent $2.8 million on maintenance – more than twice as much as CEC – despite having a third fewer customers, according to state figures.

”Our costs should not be higher than CEC’s,” Kopacz said. ”I don’t think our maintenance costs are higher or lower than the average.”

But CEC spokesman Crowell said that data actually is an indicator that his cooperative’s system is in good shape.

”Low maintenance expenditures are a sign of a well-built electric system if the average hours of outages-per-customer are low,” Crowell wrote, in a statement about the company’s maintenance spending.

CEC reported just 1.1 hours of power outage per customer in 2004, 1.85 hours in 2005 and 1.3 hours per customer in 2006, placing the cooperative in the top third of cooperatives nationally.

One of CEC’s biggest customers, Hoodoo Mountain Resort President Chuck Shepard, said the company’s service has generally been good.

”When power goes out they’re very responsive for the most part,” Shepard said. ”We wish there would be some improvements to the lines going out, but I know they’re not necessarily in control of all of that.”

Kopacz declined to comment on the condition of CEC’s electrical system. In general though, deferring maintenance can lead to expensive problems that only surface three to five years later, he said.

”If you had a decrease of maintenance, you’re going to have a decrease in your reliability and you’re going to have more unexplained outages due to equipment failure,” Kopacz said. ”If that does occur than you could have a greater maintenance cost or expenses in the future due to upgrading or replacing of equipment that failed or wasn’t properly maintained.

”You can get by for a short period of time,” Kopacz continued. ”Then you’re asking for poor reliability after that.”