Teachers in region submit to AP audit

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 15, 2007

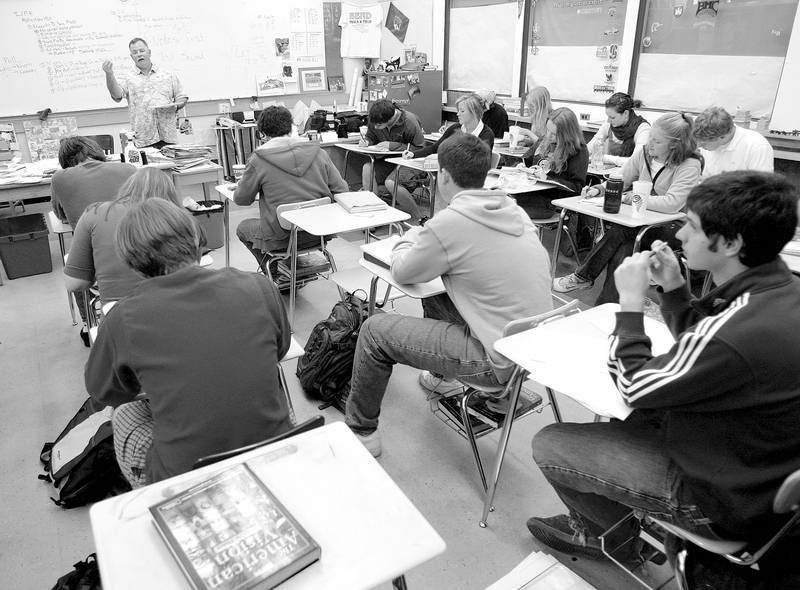

- Doug Brown, an Advanced Placement history teacher at Bend High School, talks about an upcoming test. The College Board, which runs the program, is asking AP teachers to do course audits to make sure their classes are meeting the standards of the AP label.

Like other Advanced Placement teachers throughout the nation, Nick Kezele has recently had to juggle grading tests and planning lectures with a big homework assignment of his own.

The AP phy-sics teacher at Madras High School estimated he has spent between 10 and 12 hours completing an AP course audit required by the College Board, the New York-based nonprofit agency that runs the Advanced Placement program and the SAT and PSAT tests. In doing so, Kezele had to sift through his course syllabus for the year for an online form the College Board will use to determine whether he is meeting the standards of the AP label.

The board decided to run its first audit in the AP program’s 51-year history to evaluate whether the courses are meeting AP standards. It’s seen exponential growth in the number of AP classes offered in the last 10 years: Between 1995 and 2005, the number of students in AP classes worldwide went from 504,000 to 1.2 million, said Tom Matts, director of the AP course audit for the College Board.

AP offerings are in-depth, college level courses taught in high school. Students who receive a passing grade on a cumulative AP test offered at the end of the year can earn college credit while still in high school. A passing grade is generally a 3, 4 or 5 on a 1-to-5 scale.

Given the burgeoning number of AP courses peppering student transcripts, college admissions staff began to wonder if the classes are really a good indicator of achievement.

”The admissions officers are wondering, ‘How have you modified that curriculum in order to accommodate this 142 percent increase in the number of students taking the courses?’” Matts said.

While it means more work for Kezele and his colleagues, some AP teachers in Central Oregon agree that such scrutiny is valid. In Central Oregon, the number of AP classes offered has increased over the years, as well.

”In the scope of things,” Kezele said, ”it’s one more thing to do and you’ve already got a full plate, but I think it’s perfectly reasonable for the AP folks to ask us so they can be ensured that they’re getting that curriculum.”

Once the audit is complete sometime this fall, colleges, parents and students will be able to check an online ledger to see if a particular teacher and course has met AP standards.

AP in Central Oregon

Bend-La Pine Schools, the region’s biggest district, has 64 AP classes on the district’s roster – 13 at Bend High School, 16 at Mountain View High School and 35 at Summit High School. While those have been approved by the district, that does not mean all the classes are offered all the time, Summit Principal Lynn Baker said.

In 2005-06, 485 total students, or 11.4 percent of students in grades nine through 12, enrolled in at least one AP course, said Vicki Van Buren, Bend-La Pine executive director of secondary programs. That year, the pass rate of the 305 students who took the exams was 55 percent. Worldwide, the passing rate was 59.6 percent, Matts said.

Other area school districts also participate in the AP program.

The Redmond School District offers five AP classes but plans to add several more in the fall, said Michael Bremont, assistant principal at Redmond High School. The school plans to add AP human geography and art history, and hopes to offer AP music theory to the course catalog if it can find a teacher.

”As we encourage kids to attend college, we want to offer courses that will prepare them for that,” Bremont said. ”There’s a lot of research regarding students’ success in college is based on the number of AP courses that they take.”

Last year, 118 Redmond students took at least one AP course, and of those students, 116 took the AP exam at the end of it, according to data from the Redmond School District. Of that 116, 71 students took more than one test and passed them all.

In Jefferson County, seven AP courses are offered at Madras High School, said Courtney Lupton-Turner, AP coordinator for the school.

”We’ve been developing our program through the years,” she said.

With intense competition to get into colleges, Lupton-Turner said she hopes students are taking AP courses for the right reasons.

Some students focus on the AP label because it looks good on transcripts, she said. But at $83, the AP placement tests can sometimes be a stretch.

”I think our AP courses are great,” she said, ”but there are other choices, too.”

If students want a challenge, they can participate in a dually enrolled program with Central Oregon Community College. They can also take part in extension programs from colleges, such as Portland State University and Oregon State University, she said.

What makes a class AP?

Advanced Placement teachers say their course work is college caliber, pushing students to excel to that level.

AP calculus teacher Denny Irby, a teacher at Redmond High School, estimates his students average about 10 hours per week outside of his class on homework.

”In a normal high school class, they might be expected to put in somewhere around two to three hours a week,” he said.

Their tests, geared toward the AP calculus exam at the end of the course, are different, too.

”It’s an hour and a half portion of the test that are essentially story problems, that are going beyond what you would normally see in math class, or even in a textbook because there are several parts to it – as many as four to five parts to a single problem,” Irby said.

Another thing that distinguishes AP calculus from other courses is the way that students must make connections between things they learned in the early part of the year and what they learned toward the end, Irby said.

Irby submitted his audit several weeks ago but has not heard back yet, he said.

Mike Miller, who teaches an AP chemistry class at Bend High School, describes his course as a university level introductory chemistry class. His list of topics includes structure, properties and states of matter, periodic properties of the elements, chemical reactions, equilibrium and kinetics.

The AP suggested topic list includes many of the same concepts – equilibrium, kinetics and structure of matter. The list also addresses thermodynamics, reaction types and an introduction to organic chemistry.

Miller said his students ideally would spend an hour and a half each night working on chemistry homework.

”In a regular class, they usually have enough work time to finish their work in class,” he said.

He quizzes students three times a week and expects them to keep up with their lab work.

Plus, the problems students must solve are more complex than those addressed in regular chemistry classes.

”Questions in AP are more likely to require an explanation rather than just an answer,” he said. ”They’re more likely to have to write an answer which shows that they understand the concept as opposed to choosing an answer from a list of multiple choice. And rather than multiple choice, the tests are open-ended problem solving, open-ended written answers to questions.”

As for Miller, he got some good news Monday: He received an e-mail saying his course passed muster with the AP board and will be on the roster of authorized AP classes slated to be released in November.

Doug Brown describes his AP Government and Politics class at Bend High School as longer, harder and more in-depth than a regular government class.

”It covers more than the sort of foundations that our government goes into,” he said. ”It’s just more detailed.”

Per AP requirements, Brown uses a college-level textbook in his class, called ”Government in America,” by George Edwards III. The book is on the College Board’s sample curricular requirements list for AP U.S. Government and Politics.

His students have read about the Constitution and Federalism in the Edwards text, but Brown also supplements his readings with news articles. Recent news articles assigned include stories about the Oregon’s ”kicker” law and Scooter Libby’s subpoena.

A sample curriculum requirement from the College Board Web site suggests incorporating current events into student reading lists.

Students in Brown’s class say they can, in most cases, see a clear distinction between AP and regular courses.

”Teachers treat you differently,” said Leah Lansdowne, 18. ”There’s a huge amount of respect between teachers and students.”

Leah, studying for a test with some of her classmates, said she hopes to take the AP test and receive college credit.

AP teachers have higher expectations of their students, said her classmate, senior Ben Brewer.

”They expect you’re here to learn as much as you can about the subject,” said Ben, 17.

Ben had heard about the audit and said it seemed fair.

”They should be able to keep track and make sure we’re not just sitting in here,” he said. ”But for the teacher, it could be an extra burden.”

Hard work

Kezele said he has few opportunities to veer from the AP guidelines in his physics class.

”The board specifies what topics must be covered in the class, so you’re pretty much required to cover those topics,” he said. ”They don’t have to be done in any particular manner, but there must be a minimum of 12 laboratory exercises that are student-centered and, as much as possible, inquiry-based.”

In a general physics class, Kezele – who has been teaching the AP version for nearly nine years – said he would have more freedom in how much time he allots for different topics. But AP teachers have the added pressure of teaching to the test. Last year, Kezele said three students took the test and all three passed. Normally, his classes range from 14 to 20 students.

Offering AP classes also takes a lot of time, work and money, Lupton-Turner said.

”It’s expensive,” she said. ”Textbooks are probably $100 each.”

A regular textbook costs around $60, said Lupton-Turner, who is also the talented and gifted specialist for the Jefferson County School District.

Plus, the district must purchase lab materials and workbooks and make sure enough students sign up to make the course worthwhile.

”In the past, what we did was develop in-house with the principal and the teachers, we’d come up with recommendations, a syllabus, a plan,” Lupton-Turner said, ”and then go through the steps to get it approved through the curriculum council and the school board.”

Teachers must also be qualified to teach AP courses, said Baker of Summit High School. He said the school typically offers 10 to 12 of its 35 AP-approved courses each semester.

AP teachers must attend training sessions offered by the College Board, he said. They must also have a license to teach upper-level classes.

”As far as the AP folks, I think they’re most concerned about having a teacher who has been trained in AP instruction and practices,” Baker said.

About the audit

The audit will serve several purposes, said Jennifer Topiel, a spokeswoman for the College Board.

”It will give teachers and administrators at schools clear guidelines for the curricular and resource requirements that should be in place,” she said.

For example, if a teacher is using a high school-level rather than a college-level textbook, the audit will give the teacher grounds to ask their district for more resources.

”The audit also helps colleges and universities better interpret high school courses marked ‘AP’ on a student’s transcript,” she said.

That way, colleges can ensure that students have completed a course at an expected standard.

Teachers have until June 1 to submit an electronic copy of the syllabus outlining the course of study their class will follow for the 2007-08 academic year.

According to the College Board Web site, ”The syllabi must provide clear and explicit evidence that the AP Course Audit requirements are included in their courses.”

Teachers must also fill out an online course-specific audit form, which asks about the units studied, content taught and course work assigned for each topic.

So far, about 46,000 teachers have submitted their syllabi for review. Of those that have been reviewed, about 82 percent have been approved on first review, said Matts from the College Board.

The agency expects to receive audits from about 130,000 AP teachers worldwide.

More than 600 college professors who either currently or have recently taught a college course in the same subject as an AP course reviewing the audits.

If a course is not accepted on first review, the board will send it back with feedback and ask the teacher to resubmit the audit. They get three opportunities to submit their syllabi, Matts said.

He said the College Board wants teachers to pass, and will tell them what they need to do to get there.

The College Board hopes to have an online ledger available by November that would list ”authorized” AP courses – those courses and teachers that have passed the audit.

Most area administrators agree the request for an audit is valid.

”I have to say, I do think it’s a good idea for the College Board to certify that the courses that carry a label of AP truly are advanced placement, because AP was a program that was started eons ago,” Van Buren said. ”The intent behind it was to teach college-level courses at high school, and there needed to be some type of certification process.”