Tea time: Mint leaves have global following

Published 5:00 am Monday, September 24, 2007

- Tea time: Mint leaves have global following

CULVER — This year’s mint leaf harvest has all but ended, with most Central Oregon mint leaves dried and sent to processors for cleaning. Loren Roff, though, still has one field remaining, and it’s the last mint standing in the region, he said.

The Culver farmer grew about 120 acres of mint this year on five different fields, but this 30-acre field was damaged by a rain and hailstorm late last month and remains uncut. “It’s my poorest field this year,” he said. “It seemed like every time we got sunshine in the forecast, we would cut our field and it would rain.”

Farmers will cut, or swath their fields, and let the leaves dry for five to seven days before harvesting, Roff said.

If it rains during that time, the mint leaves become darker green in color.

“You don’t want it to rain on a (drying) tea leaf,” he said. “You want your leaf to be a nice, bright green in color.”

Most of the region’s mint crops have been shifted from being grown for oil — including essential oils, which require longer growing seasons and cost more to produce — to mint leaves for tea, according to agricultural officials who say the region’s mint leaves are sought after by tea companies in the United States and abroad.

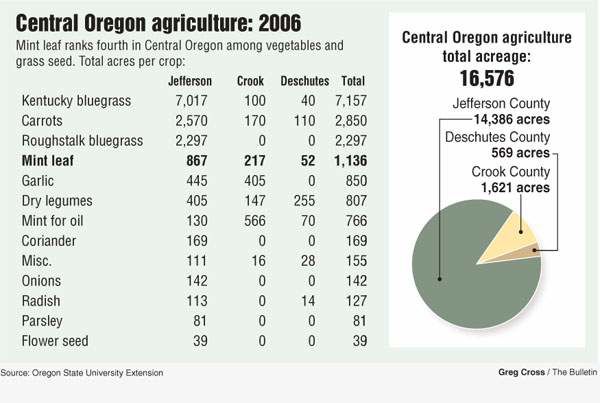

Farmers in Jefferson, Crook and Deschutes counties grew 1,136 acres of mint leaf for tea with a crop value of $1.3 million in 2006, according to the Oregon State University extension office.

Boulder, Colo.-based Celestial Seasonings buys roughly 400,000 pounds of Central Oregon mint leaf per year, said Mike Weber, managing partner at Madras-based Central Oregon Seed Inc.

For all intents and purposes, Celestial Seasonings (mint) tea is from Central Oregon, Weber said.

“We’ve had a full contract (with the company) for 10 years,” he said.

In total, Central Oregon Seeds processes and sells between 2 million and 2.5 million pounds of Central Oregon mint leaf per year. Its other domestic tea buyers include Tigard-based Stash Tea Co. and Portland-based Tazo teas, Weber said.

Celestial Seasonings scours the globe, including 35 countries in South America, Asia and Africa, looking for the best peppermint and spearmint teas, said Kay Wright, botanical purchasing director for the company.

Central Oregon provides the company with most of the mint leaves for peppermint and spearmint teas, she said.

“It’s the best mint in the world,” Wright said. “Nothing compares to domestic mint produced in the Pacific Northwest.”

The crop provides much-needed diversity for Culver farmer Roff, who needs as many crops as possible on his 750-acre farm to shield him from risk if one crop fails.

This year, his crops included wheat, carrot seed, garlic seed, alfalfa for hay, and Kentucky bluegrass seed, he said.

He can yield more on his mint leaf crop by “double-cutting,” which means cutting the same field twice, he said.

“Typically, the Americans will get the single-cut stuff because they like their tea strong and the double-cut goes overseas because they like a lighter tea,” Roff said.

But from the looks of this field, the second cutting will not be too lucrative, he said.

“It won’t make you rich,” Roff said.

Summer rains and a dry and cold winter cost Lynn Lundquist, a Powell Butte farmer and Crook County commissioner, about 10 percent of his mint leaf crop this year, he said.

“Production-wise, it was the poorest crop we’ve had in a long time,” he said.

Crook County farmers rely more upon crops like mint leaf and mint for oil because their higher elevation limits crop diversity. Other crops include hay, and livestock and grain crops.

The county is about 1,000 feet higher than Jefferson County, shortening its growing season by about a month, Lundquist said.

Within the last seven to eight years, mint leaf has become Lundquist’s “major crop,” he said.

“It’s the crop that replaced oil,” Lundquist said. “There are so few alternatives to grow because of weather conditions, particularly in Powell Butte.”