Arthritis in young joints

Published 4:00 am Thursday, December 7, 2006

- Arthritis in young joints

Picture an individual with arthritis and it’s likely to be an older woman rubbing her sore hands, trying to get some relief from the pain and the stiffness. Chances are you wouldn’t picture 8-year-old Laurel Johnson snowboarding or 6-year-old Emily Brockman playing soccer with her brother on the front lawn.

Yet the two girls, both students at Highland Elementary at Kenwood in Bend, have had to battle juvenile forms of arthritis well before they could truly comprehend what was happening to their bodies.

”She has the eye thing, and I have the leg thing, but I think she also has the leg thing,” Laurel said in the school hallway last week.

”Yeah, I do have the leg thing, too,” Emily replied.

On Saturday, the two girls will serve as grand marshals of the Jingle Bell Run, a fundraising event to benefit the Arthritis Foundation and raise awareness about the disease. But it’s likely the mere presence at the race of two little girls with arthritis will say more about the impact of the condition than their words ever could.

”It’s not just a disease the elderly get; it’s a childhood disease,” says Toni Brockman, Emily’s mother. ”We just want to get the word out that it is something that kids get, too.”

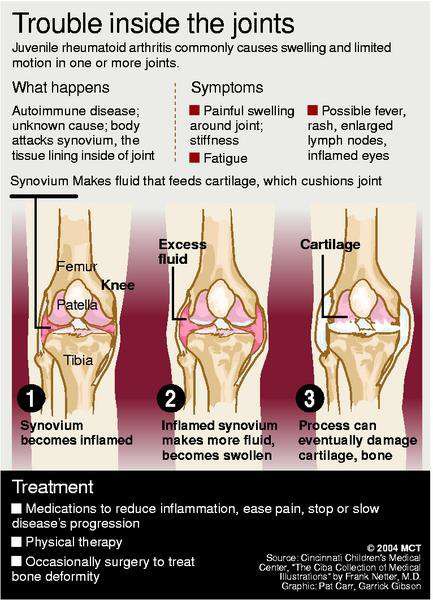

Juvenile arthritis is a term used to describe a variety of conditions involving inflammation of the joints and other symptoms. It affects some 300,000 children in the United States, occurring about as often as insulin-dependent, type 1 diabetes.

Despite the prevalence of juvenile arthritis, it can be a difficult condition to diagnose and treat. A lack of awareness of early warning signs, along with a shortage of specialists, means many children often go without a diagnosis for unacceptably long periods of time. And the longer treatment is delayed, the more potential there is for irreversible joint damage or other complications to occur.

Missed signals

The diagnosis is often missed or delayed because the symptoms are commonly attributed to other causes, such as growing pains, a fall or an athletic injury. And because the condition can take many forms, there is not a single set of symptoms to guide parents and doctors.

”It can range anywhere from a child having very high, unexplained fevers and rash with some joint pain, to someone who has just two or three swollen and inflamed joints and otherwise feels totally normal,” says Dr. Dan Fohrman, a rheumatologist at Bend Memorial Clinic. ”Young children may not have any pain whatsoever. And because we usually associate pain as the primary symptom of a problem, it can be very misleading.”

Often, particularly with very young children, the only sign that something is wrong is an unwillingness to use a particular joint.

”They’re not complaining of pain, they’re just saying I can’t bend it or straighten it,” he says. ”They don’t walk when they should be walking or they don’t want to straighten an arm.”

That’s how Michelle Johnson discovered Laurel’s arthritis. When Laurel was 18 months old, a neighbor pointed out that she walked a little stiffly.

”Right about the same time – I had not tied them together – she was waking up with very high fever, like 103, 104 fevers, screaming out,” Johnson says. ”Then the next day she’d be perfectly fine.”

While doctors initially told Johnson there was nothing wrong with Laurel, a year of visits to specialists ruled out other possibilities and finally settled on the diagnosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Despite having seen a television report on the condition only a month before her daughter was diagnosed, she had never considered her daughter might have arthritis.

”It had never crossed my mind,” she says. ”I was quite surprised and quite shocked, and I was also very frightened.”

Shortage of specialists

To complicate matters, there was no pediatric rheumatologist in Oregon when her daughter was first diagnosed. The Johnsons had to make several treks to Seattle to visit Dr. Daniel Kingsbury, the closest specialist to Bend at the time. Kingsbury has since relocated to Portland, leaving Central Oregon families a shorter but by no means convenient trip.

”It was very difficult, because it was driving over the mountains in the snow, living over here and trying to correspond and work with a doctor over there,” Johnson says.

According to the Arthritis Foundation, there is a nationwide shortage of pediatric rheumatologists, with only 200 of the specialists scattered among major cities throughout the U.S. The group has been lobbying Congress and the federal government to provide more support for pediatric rheumatology training programs and to create a loan repayment program to encourage specialists to enter the field.

Those efforts also include a push for greater research funding, which advocates argue lags behind spending for many other conditions.

Evolving field

Piggybacking on adult arthritis research, new treatments are being introduced on a regular basis.

”We have very good treatments that are now available, many of which weren’t available even five years ago,” Fohrman says. ”A significant number of these children will go into remission as they get older, usually in their late teens and into their early 20s. We don’t want to be overtreating children any more than we want to be undertreating them.”

Today’s arthritis treatments involve new biologic drugs and other medications that require specialized knowledge for effective administration and monitoring. That makes the involvement of a pediatric specialist even more important. By default, adult rheumatologists, such as Fohrman, as well as general pediatricians have overseen the care of children with juvenile arthritis locally under the guidance of a specialist from a distance. While the arrangement is not ideal, it helps to ensure the children can get more aggressive treatment when it’s required.

Laurel had to wear a leg brace when she was first diagnosed and endured a long series of steroid injections and other medications to treat the inflammation. She has not yet regained a full range of motion in her leg. While it doesn’t stop her from playing soccer or baseball or doing most other physical activities, there is a chance that she may never regain that mobility.

Emily was diagnosed within the last year after her parents noticed her leg had swollen. She was also diagnosed with an inflammation of the eye, something that often accompanies juvenile arthritis but has no outwardly visible symptoms. The Brockmans were advised to see an ophthalmologist after she had been diagnosed with juvenile arthritis.

”They found the inflammation in her eyes,” Brockman says. ”We felt kind of lucky that the knee swelled up because the eye thing, that can eventually lead to blindness if it’s not caught.”

Fohrman says the possible eye complications are important to catch and treat early because of the potential for long-term damage.

”It’s often the eye involvement that’s been far more of an issue into adulthood than the joints because the joints often go into remission,” he says.

Doctors will continue to monitor both girls to see whether their symptoms return and require additional treatment.

”It’s different with every kid,” Brockman says. ”The hope is that they grow out of it. A lot of times, it’s kind of ongoing and you just have to deal with it.”

Both girls are dealing with it very well, as evidenced by the fact that they are excited about serving as grand marshals for the race this year and that neither is content to just stand on the sidelines and wave.

”I’m going to do the race,” Laurel says. ”I’m going to do it with my friend.”

”Me too,” Emily adds.

Want to help fight juvenile arthritis? Organizers of the Jingle Bell Run are still looking for volunteers to help on race day, runners to participate in the event and donations for arthritis research and support. Contact: 503-245-5695 or 888-845-5695.