Derrick Cave

Published 4:00 am Friday, February 17, 2006

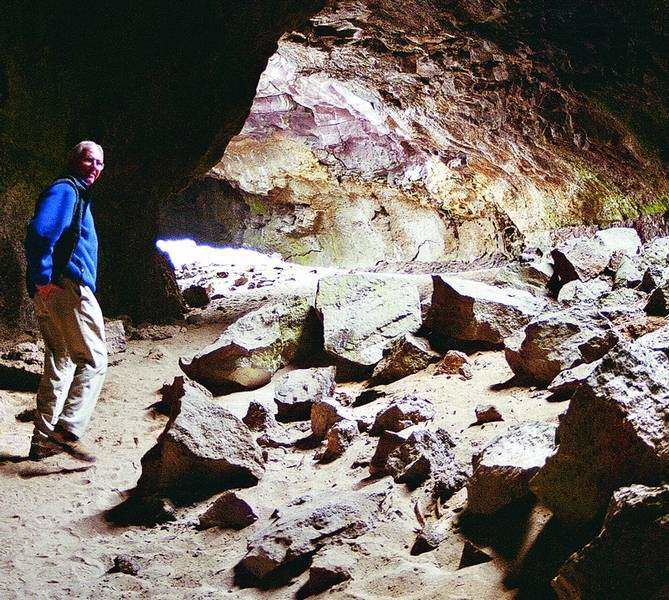

- Jeff Grimm, of Bend, explores Derrick Cave in April 2001. The lava tube is southeast of Bend.

Aside from the standard oohs and aahs big caves invariably elicit, what’s most impressive about this one is what’s not there.

Standing inside Derrick Cave, about 45 miles southeast of Bend, you have to imagine the raging river of super-heated liquid lava coursing through the 1,200-foot-long tube thousands of years ago.

It’s not hard to do. In this neck of the woods – on the northern edge of Fort Rock Valley – signs of volcanic activity are everywhere. But none is more dramatic than this lava tube through which the molten magma passed. What’s left is a large hole in the ground and a cavernous cylinder with a boulder-littered floor snaking away from the light.

It’s a good 15 or 20 degrees cooler inside the cave, and you don’t have to travel very far inside before you come upon ice underfoot. The slippery kind.

With blazing headlamps illuminating our way, we shuffle gingerly over the ice and pick our way over and around slick jumbles of smooth volcanic rock.

I’m fascinated by caves in the abstract, something just this side of terrified of them when I’m inside, breathing the musty-cool air and studying the clumps of rat midden and the cold, lifeless rocks bathed in weak rays of artificial light strewn randomly along the floor of the tube.

Each of those big rocks – boulders some of them – fell from the roof at intervals through the millennia, explains my caving partner, Jeff Grimm, a geology student. Each of those projectiles would squash a hapless subterranean intruder like a bug, I’m thinking, if the bug was unfortunate enough to be scuttling across the cave at the convergence of geologic and daylight-saving time.

Grimm recalls a recent hike during which a large boulder, dislodged up-slope, came tumbling down the mountainside in his general direction. He dove out of the way. The boulder missed him but the fall messed him up pretty good.

I’m thinking about that and all the people who win the lottery as the darkness pulls us inexorably forward. Finally, the unsure footing makes going any farther seem foolhardy, so we retreat, back around the corner to the sunlight streaming through a skylight opening in the roof and then the entrance.

According to ”Central Oregon Cave Book” by Charlie and Jo Larson, Derrick Cave was part of a river of lava that began at a vent at the northeast corner of Devil’s Garden, a 45-square-mile lava field on the northern edge of the Fort Rock Valley. Most of the lava that ended up in the garden passed through Derrick’s gut.

According to the authors, the main entrance to Derrick Cave and skylights probably resulted from collapses that occurred after all the lava drained out of the tube.

It’s essential to carry either flashlights or headlamps into the cave unless you plan on going only as far as the sand-floored main entrance area.

Back outside at the car, it’s less than a mile south on Road 23 to more dramatic evidence of the region’s explosive past. The blowout, a hill of volcanic debris that looms a few hundred feet above Devil’s Garden, is a cone from whence lava burbled and spat. It gives a good view of the surrounding countryside as does Green Mountain farther to the south. Both give new meaning to the term big air after the claustrophobic confines of the cave.

The road between Highway 20 and the Derrick Cave/Blowout area takes you around to the back side of Pine Mountain and through an improbable forest of lodgepole and ponderosa pines.

Fill up the gas tank before you explore Road 23 and, if you bring your dog, you might consider booties. The lava cuts up paws as well as shreds boot soles.

And check the weather conditions before you go.

-Jim Witty