Ashland’s Shakespeare Festival ranks high among nation’s regional theaters

Published 5:00 am Sunday, July 16, 2006

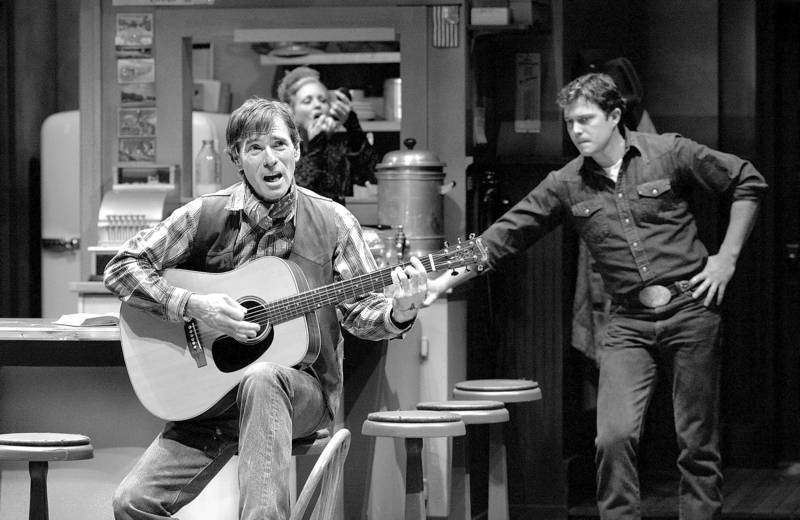

- Actor Mark Murphey plays the guitar in a scene from the festival's 2006 production of the William Inge play ”Bus Stop,” in the black box-style New Theater. Murphey, in his 25th season at the festival, is its longest tenured actor.

Oregon is a long way from Broadway.

But, luckily, Oregonians don’t have to travel far for great theater: A scant 180 miles away from Bend resides one of the premier regional theater companies in the country.

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland is, without a doubt, a glittering jewel. It boasts three state-of-the-art theaters, 11 plays, an eight-month season, a budget of more than $22 million and a talented stable of actors, directors and support staff.

It is, according to a Time Magazine article published in 2003, one of the nation’s top five regional theaters, bested only by Chicago’s Goodman Thea-ter.

You get the point.

But the praise is deserved. If you enjoy theater, the festival ought not to be missed. No detail is overlooked, from costumes and sets to special effects.

And, if you shudder at the thought of sitting through three hours of Shakespeare, you should know that only four of the festival’s plays are by the Bard. The rest of the bill consists of both contemporary works and well-worn classics.

Broadway is still this country’s pinnacle of theater, and that won’t change anytime soon. But there is plenty to feast your eyes upon in our own backyard.

A trip to Ashland

It takes roughly four hours to reach Ashland from Bend, as the most direct route is a picturesque two-lane highway that winds past Crater Lake on its way over the Cascades.

The town itself is located 13 miles south of Medford, astride Interstate 5. It has a population of 20,000 and is also home to Southern Oregon University.

Due to the demands of both the festival and the university, Ashland has a wealth of lodging options, from Shakespeare-themed inns and bed and breakfasts to the stately Ashland Springs Hotel, a nine-story downtown hotel that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

A list of lodging options can be found on the festival’s Web site, www.osfashland.org.

The festival’s theaters and the box office are also located in Ashland’s downtown, making them within easy walking distance of the many restaurants and bars that dot the downtown core. Also in downtown Ashland is the entrance to Lithia Park, a bucolic 100-acre greenway whose trees help form the backdrop for the festival’s open-air Elizabethan Stage.

Of the festival’s three theaters, the Elizabethan is the granddaddy. It was built in 1959, and patterned after London’s old Fortune Theatre. The Fortune existed when Shakespeare was alive, and is the only theater from the period whose dimensions are exactly known.

This tidbit is just one of many you can learn about on the festival’s Backstage Tour. It lasts roughly two hours, and is wildly fascinating. A festival actor takes you on the tour, and it includes a walk through the Elizabethan’s backstage and a stop in the dressing room complex underneath the stage.

The Elizabethan is as ornate as the era it’s named after. It has a thrust stage, balconies and numerous windows and doors in its superstructure that open to the audience.

The Elizabethan also has two vomitoriums. Before you jump to conclusions, vomitoriums were what Romans called the passages that allow spectators to enter a stadium. The term has been borrowed by the theater to describe an alley cut into the amphitheater that is solely used by actors to mount the stage from the front of the house. The festival actors call them ”voms” for short.

The Elizabethan used to open onto the street, but in 1992, the Allen Pavilion was completed. It is a three-tiered stadium-style amphitheater that provides seating for close to 1,200. It is named after Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who made a large donation for its construction.

Most of the festival’s Shakespeare plays are performed outside on the Elizabethan Stage. It annually opens three plays in June, which run through October. Playing on the stage this year are ”The Merry Wives of Windsor,” ”The Two Gentlemen of Verona” and ”Cyrano de Bergerac.”

”Cyrano,” of course, was not written by Shakespeare, but by the Frenchman Edmond Rostand, proving that the festival is not all Shakespeare, all the time.

Shakespeare, however, is the attraction for most of the actors who are members of the festival’s acting company, said Michael J. Hume, an actor in his 15th season with the festival.

”Shakespeare is why we all come here, I think, that outdoor bowl, was sort of the initial draw for everybody,” Hume said.

Some actors don’t like working in the Elizabethan because ”it’s a specific animal to tame,” said Hume. Because of the size of the theater, and the fact that the actors don’t wear microphones, they concentrate less on ”acting” and more on vocal projection.

It’s a challenge, Hume said, but one he loves.

”I love the Elizabethan, I really do,” said Hume. ”It really was the draw, going, ‘God, look at the size of that space,’ and ‘I could play out there?’”

Hume, 54, has not been cast in an Elizabethan play for four years, and misses the experience. He has appeared onstage in the theater as an understudy, but those were only to fill in because the principal couldn’t make the performance.

Repertory company

The festival is set up as a repertory company, so that each of its 88 actors performs multiple roles each season. An actor can be cast in as many as three plays, and also serve as an understudy for roles in other productions. Each actor signs a 10-month contract, and it’s the closest thing to job security in the world of acting.

”The only other thing is to be on a soap opera,” said Tyler Layton, an Alabama native who is in her sixth year with the festival.

Partly because of that security, Layton said the festival draws many talented actors, some who stay for years. The longest serving actor is Mark Murphey, who has been with the festival for 25 seasons.

There are other factors that attract actors, including the repertory format. Instead of performing a play eight times a week for a month, the festival’s actors perform eight times a week, but in different plays, which can run for months.

”I prefer it,” said Layton. ”It mixes it up a little bit.”

This season, Layton performs outdoors in ”The Merry Wives of Windsor,” and is one of the stars in ”Bus Stop,” a contemporary play being staged in the festival’s New Theatre.

The festival’s newest theater, hence the name, the New Theatre replaced the Black Swan Theater, which was an old gas station garage the festival had converted into a black box-style theater.

Opened in 2002, the New Theatre retained the black-box format. A black-box theater is intimate, featuring a stage surrounded on three sides by an audience that is never more than seven rows from the stage.

A vast improvement over the Black Swan, the New Theatre was built with up-to-date theater technology. For instance, the floor hides a multitude of trapdoors, its ceiling brims with hundreds of stage lights, and adjustable seating allows the stage to be configured in a variety of ways.

The theater is so quiet, ”You can sort of mumble your way through,” quipped Layton, who prefers acting in the New Theatre to the shouting she has to do in the spacious Elizabethan.

Growing up in Alabama, Layton, 38, said she didn’t have much exposure to Shakespeare. Instead, she was inspired to pick up acting after a childhood trip to Broadway with her parents. While she was earning a master of fine arts degree from the University of California, Irvine, however, a professor there turned her onto the Bard, and she ”fell in love with it.”

Performing Shakespeare can be a challenge, Layton said, but she likes acting at the festival, especially for the variety of roles it provides. And she likes the camaraderie the company affords.

Layton once dreamed of performing on Broadway, but is discouraged by the growing trend of casting Hollywood actors. The result is stars who don’t play off each other, but instead try to outshine each other.

”Whereas this place, these people have been working together for years,” Layton said. ”It’s a company. There are no stars at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.”

The Bowmer

The festival was founded in 1935 by Angus Bowmer, a teacher at the then-Southern Oregon Normal School who thought it would be fun to stage a production of the Shakespeare comedies ”Twelfth Night” and ”The Merchant of Venice” over the Fourth of July weekend.

Bowmer borrowed $400 from the city to produce the plays, which were staged on the site where the Elizabethan Stage now sits.

Ironically, the town’s fathers thought the festival was going to be a disaster, so they arranged a boxing match beforehand. The boxing match, however, lost money, while the festival was a success.

Each year, the festival grew, although it went on hiatus from 1941 to 1946, when Bowmer enlisted in the Army.

In 1960, the theater staged its first play by someone other than Shakespeare, John Webster’s ”The Duchess of Malfi.” Now, the majority of the festival’s plays are by playwrights other than Shakespeare. This year’s festival includes plays by William Inge, Oscar Wilde, Bridget Carpenter, David Edgar, Lynn Nottage, Francis Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

Many of these are staged on the festival’s 600-seat Angus Bowmer Theatre. It opened in 1970, and has a modified thrust stage, vomitoriums and an elaborate system of hydraulics for changing its sets. The Bowmer, as its called, is the festival’s busiest theater, as it’s home to as many as five concurrently running plays.

The Bowmer also allowed the festival to extend its season. Thanks to climate control, productions in the Bowmer open in February and can run until October.

It also traditionally hosts one Shakespeare play per season. This extra venue has helped the festival produce the entire Shakespeare canon three times and start its fourth cycle.

For the trivia buffs, the festival’s most produced play is ”Twelfth Night.” It has run in 15 of the festival’s 71 years.

New artistic director

Shakespeare will always be an integral part of the festival, but change is on the horizon. The festival’s artistic director, Libby Appel, has announced her retirement after the end of the 2007 season. Appel is just the third artistic director to serve with the festival since Bowmer’s retirement in 1971. He died in 1979.

The festival office hopes a new artistic director will be named in the coming months, but Hume isn’t worried. Change is always good, he said, but he doesn’t expect much of it.

”Any artistic director coming in, they have to realize they’re not gonna be able to create a revolution with it. They are being handed a baton that is basically a stewardship,” said Hume.

Maybe that will mean more plays by contemporary American playwrights, such as David Mamet and Sam Shepard, Hume said. Appel’s artistic sensibilities are more European, he added.

Whoever assumes the helm will inherit a treasure. It’s a well-oiled clock, Hume said, a place where ”everything is covered.”

”The cliche here is you can sneeze and there’s five boxes of Kleenex around,” he said.

Wealthier than most theater companies, yes. But the festival is also home to some of the best theater around.

”I’ll go see something on Broadway, then see it here, and it’s just night and day,” said Layton. ”It’s some of the best theater going on in this country.”