Will Bend be a wildfire success story?

Published 5:45 am Saturday, January 18, 2025

- Laurence Le Mercier explains elements of the defensible space that she has created around her Bend home such as minimal vegetation and clear space between houses.

Less than two weeks after her California home was damaged and nearly lost in the Eaton fire burning in Los Angeles — one of a group of blazes fanned by hot winds and parched air responsible for destroying thousands of structures and killing at least 25 people — Bend resident Brenda Cullen had already begun thinking that her home in Bend would someday suffer the same fate, or worse.

“Thankfully, we have another place to go,” Cullen said at a Thursday meeting of the Project Wildfire Neighborhood Coalition, a group of community members and fire officials formed in 2023. Citing Central Oregon’s dry conditions and summer winds, she feared the pace at which the group was working to make neighborhoods across Bend less likely to burn was not fast enough.

Trending

“That’s not going to save Bend from something like what happened in LA … it’s really not a matter of looking out 10 years before something like this happens,” she said.

As Southern California burned, alarm bells filled the heads of Central Oregonians. Questions and concerns about whether Bend was prepared flooded city offices, prompting the city to publish a website with new evacuation and fire information. Meanwhile, the fire department was mobbed with more than 100 requests for free home inspections on ignition risk, nearly as many as the department received in all of 2024.

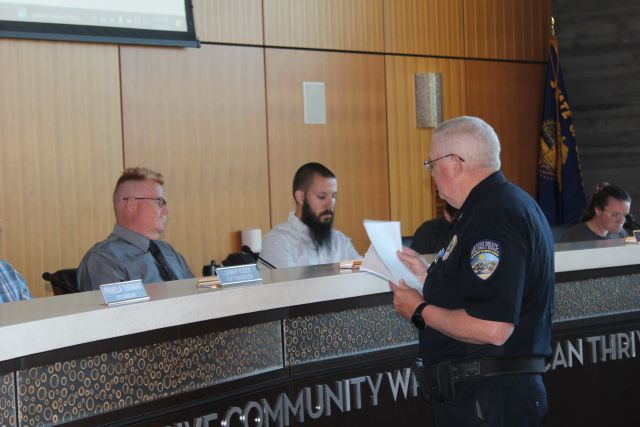

“I am now booked out ‘til May,” said Melissa Steele, fire inspector for the city of Bend, at the meeting.

Bend’s continued growth means more people than ever live on land where fire has been a regular — and necessary — occurrence for thousands of years. The fires are becoming more frequent and intense as climate change extends hot and dry seasons, making them difficult and costly to fight. Fire-minded residents are doing what they can to prepare and pushing the city government to look at new policies, hoping it may be enough to save homes and lives the next time a blaze burns toward Bend.

Steele said at the meeting she hopes actions now will turn Bend into a fire success story.

“Deschutes County has always had high fire risk,” Steele said. “It’s a shame this had to happen for people to open their eyes and know where they live. However, we’re taking it as an opportunity.”

Trending

“The city of Bend is behind, we’re behind on fire,” Steele added. “Anybody in the fire service will tell you that.”

A perfect storm

Like the winds that fueled the California fires, the new heightened awareness and hysteria over Bend’s vulnerability to destructive wildfire also came as a perfect storm, said Steele. On Jan. 7, the day the fires began the torrent, Oregon officials announced they had finalized a statewide wildfire hazard map that will be used to determine which properties must comply with pending building and landscape codes to protect against fire.

Across Oregon, 6% of properties are in the high hazard zone; in Deschutes County, the number is 40%.

Some residents are confused because the map, which was made with a computer model using data from historic fire patterns and a collaborative decision making process, sometimes draws the line separating medium and high hazard between next-door neighbors with seemingly the same susceptibility to fire. Some local fire officials are concerned that property owners with lower hazard ratings would be given a false sense of security, when in fact large wildfires can easily burn into more urban areas by chucking embers ahead of the flames, as happened in Los Angeles.

Similarly, the term WUI, or Wildland-Urban Interface, the zone where development mingles with burnable vegetation, has fallen out of favor with some.

“I don’t think you can really draw a line on a map and say ‘you’re in or you’re out’ in a place like Bend, or anywhere else in the county, where you have a mixture of wild areas and wildland fuels intermixed with neighborhoods no matter where you go in town,” said Ed Keith, who served as Deschutes County forester from 2012 to 2022.

Past research has shown that most wildfires that burn homes do so within a few thousand feet of the wildland interface zone, said Chris Dunn, a wildfire risk researcher and professor at Oregon State University who helped create the hazard map. But fires that penetrate deep into urban areas are becoming more commonplace, he said. Researchers are still trying to figure out the best ways to mitigate fires where the main fuel source turns from vegetation to buildings.

Dunn and a team of OSU staff will soon travel to Los Angeles to work on a post-fire analysis.

“We’re just kind of in awe,” he said.

Residents ask for review of codes

Still, homes next to the forest and in the High Desert would likely be the first to face a wildfire. As millions of acres burned across Oregon in 2024, smaller fires brushed with houses in Deschutes County, causing evacuations of major communities on three occasions.

One of the most destructive wildfires in Central Oregon history, the Awbrey Hall fire, burned more than 3,350 acres and took out 22 homes on the west side of Bend. Several fires since then have burned within a few miles of homes.

Robin Church and Laurence Le Mercier, who moved to different neighborhoods in the Summit West district in the last five years, are leading the effort to spread home protection practices like clearing vegetation hugging the house. They’ve received grants from Deschutes County to help with vegetation removal and participate in the Firewise USA program, which teaches people how to reduce risk of their homes burning in a wildfire. They’ve also been trained by Bend Fire & Rescue to be able to conduct wildfire assessments for their neighbors.

Despite the work, they still notice far too many trees, bushes and other flammable items like lawn chairs abutting homes in their neighborhoods. Because they often lie close together, a home is only as ready to face wildfire as the one next to it, they said. Ultimately, their goal is to connect all of the Summit West area as a wall of Firewise communities next to the forest.

Research shows Firewise practices reduce risk of homes burning, and to turn massively destructive fires into moderate ones.

But it’s not a guarantee homes won’t burn, Church said.

The city already has a code requiring landowners to reduce flammable vegetation on their properties. Church and Le Mercier believe rules around keeping up homes could be stricter. On Jan. 10, Church and Le Mercier wrote to the city council to “review and strengthen city ordinances, design guidelines, and policies related to wildfire hazard reduction and resiliency.” The letter called out wooden fencing as a particular vulnerability, encouraging the city to adopt new codes requiring non-combustible materials for fences near structures.

Getting out

While the Los Angeles fires seem to have spurred action for people protecting their homes, local emergency managers were also watching the fires with a close eye.

One major question for Bend residents is whether they would be able to leave the city in time. In Los Angeles, gridlocked traffic forced people to leave their cars and flee on foot.

That scenario saw 150,000 people attempting to evacuate quickly from a fast-moving fire, far more than would likely be on the move in Bend during a similar situation, said Carrie Karl, the city of Bend’s director of emergency management.

A major evacuation in Bend could mean 20,000 to 30,000 people leaving within a few hours. Bend’s main collector and arterial streets, which would be used to leave the city, see anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 cars each day, according to traffic counts.

“We build the routes to manage day-to-day traffic,” Karl said. “There isn’t anything in the code that says you’re building routes to manage an evacuation-level effort.”

Unlike a tsunami, which always comes from one direction, wildfire, especially in Bend, can approach from any direction. That means some of the evacuation planning must happen after the wildfire begins, Karl said.

The key is coordination between agencies, she said. Emergency managers follow plans but also keep constant coordination should new problems arise. And they have other strategies, like turning a two-lane road into a one-way funnel route, while setting up a separate route for engines headed toward the fire, Karl said.

The Deschutes County Sheriff’s Office is the lead agency for coordinating evacuations and issuing alerts for Bend and surrounding cities. The county is divided up into a handful of evacuation zones, which emergency managers use to issue alerts to cell phones, containing information on where to evacuate.

During a wildfire, evacuating before receiving the alert is never a bad idea, Karl said.

In the wake of the fires, some are worried the newest planned developments in Bend won’t come with proper getaway routes. New master-planned developments must meet the city’s fire code, which ensures emergency vehicles can properly access the area, but no development code creates standards for evacuation, said Collin Stephens, the city’s community development director.

“I’m not saying we shouldn’t, we just don’t. We don’t study evacuation,” Stephens said during a Bend Planning Commission meeting Monday. “It’s just not part of the fabric of our land-use decision making criteria. Maybe that’s something that not only Bend but other jurisdictions should be doing, and looking for direction from the state on something like that.”

As the commission recommended approval of a new 371-unit development in south Bend with two egress roads for the neighborhood, commissioner Bob Gressens echoed concerns from neighbors in the area.

“I would put a big flaming red flag next to that,” said Commissioner Bob Gressens. “What’s happening to the south of us should be a wake-up call that we revisit these existing codes.”

Growth puts pressure on fire safety

Some residents are more concerned that Bend’s growth is putting people in the path of fire. The city will need to add tens of thousands of housing units in the next few decades to accommodate growth needs, and where they will go will be a major question.

The city’s last urban growth boundary expansion was finalized in 2016, adding more than 2,000 acres to the city. The expansion was whittled down significantly from original plans, with wildfire being one of the considerations.

Since then, the city has added several hundred more acres — room for thousands of housing units — through special growth boundary additions. State law required the Stephens Road Tract, a 261-acres parcel on the edge of southeast Bend, to include wildfire mitigation. Consideration of wildfire risk was not a required consideration when the city selected Caldera Ranch, a planned 700 home development near Caldera High School, as the site of a rapid urban growth boundary expansion approved through the legislature. Brian Rankin, the city’s long-range planner, said wildfire will be a factor as the city begins planning for its next comprehensive expansion.

Ray Miao, a board member with the Deschutes Rural Fire Protection District and president of the Woodside Ranch Homeowners Association in Southeast Bend, said recent expansions and planned developments in east Bend will put neighborhoods in harm’s way.

“We can’t keep building into the desert and expect not to burn,” Miao said.

“As long as cities keep growing and doing the things they do, you’re taking down trees and putting up houses. And they’re even denser than the trees ever were,” he said during the wildfire meeting.

Because of the state’s land use system designed to curb sprawl and direct growth inward, Oregon homes are less vulnerable to burning in wildfires than in other states like California, said Dunn, the OSU wildfire researcher.

“Bend is sort of pressuring that a little bit,” he said.

More Information

Visit the city of Bend’s new wildfire preparedness website at https://www.bendoregon.gov/government/departments/fire-rescue/emergency-preparedness/wildfire-preparedness-faqs