Book review: He snuck in a suit and left with millions in diamonds

Published 9:00 pm Thursday, June 27, 2024

- books-jobb

Who among us hasn’t imagined committing the perfect heist? Ethics aside, such a crime would involve no violence, leave no one so much as injured, be carried out alone and provide a significant enough payout to never be repeated.

When Arthur Barry slipped into the Plaza Hotel suite of Woolworth heiress Jessie Donahue and stockbroker James Donahue in Manhattan in 1925, such criminal perfection was his. It was late afternoon. The stockbroker was out. The Woolworth heiress was in her bath happily chatting with her masseuse, the bathroom door ajar. Barry, alone and dressed in a tailored suit and silk gloves, walked out minutes later unheard and unseen. In his pockets: $700,000 of jewelry, a haul worth a staggering $10 million in today’s dollars.

The moment had a kind of beauty: The victims were untouched, the jewels insured, the take potentially life-altering for a 28-year-old with little education.

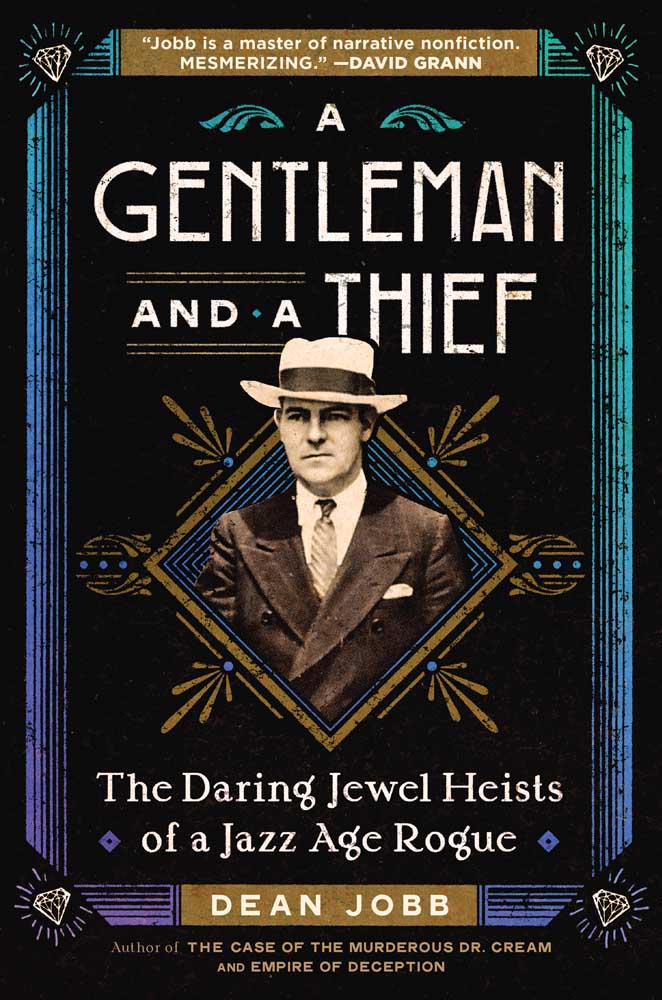

Yet Barry’s crime was flawed for one Hope Diamond-size reason: This was no one-time event upon which he blasted into that higher orbit. He had done it many times before, and he would do it many times again; over and over, in fact, pocketing untold millions. All for what larger purpose? None. And what did he do with his life, buoyed by such riches? Not much. This is a problem for “A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue,” by Dean Jobb, because for all the flickering diamonds and worsted suits, for all the references to Barry as a prince or aristocrat of thieves, it’s the story of a dissolute, empty and shallow life, too much of it spent in prison, that wears thin pretty fast.

Jobb, a veteran writer of true crime, tries his best. The chapters are short, the energy propulsive, the research prodigious. But if this aspires to be a big book, there’s not much big here. Those references feel facile, both too much and too little. Were there really more Arthur Barrys in the Roaring Twenties than, say, today? Were his crimes really specific to the times? Jobb never says. And Barry the man, especially during the 10-year height of his crime spree, remains a cipher, an empty suit, a literary type rather than a real character — a figure bereft of purpose, ideas and compelling pathos. From one leafy, hedge-rowed suburb to another, from Westchester County to Long Island, the “second-story man,” as burglars of his ilk came to be known, would find a ladder while the residents — he called them “clients” — were either gathered at the dining table or in bed asleep, clamber through a window, pilfer jewels from dresser tops or drawers, and slip out the way he came. Barry’s crimes were audacious, but not brilliant in planning or difficulty. Nor was he Robin Hood. He fenced his purloined treasures for pennies on the dollar (still a lot of money) and then would blow it all — sometimes $15,000 (in 1925 money) in a single night — gambling and drinking. Perfect crime after perfect crime, millions of dollars’ worth of rings and pearls and bracelets and cuff links in break-in after break-in. The first few are marvels. The gall of this man! The nerves of steel! The natty suit! The feckless rich people and police! But even with some slight variations, they quickly become numbingly repetitious.

Barry had just entered his 30s when the inevitable happened: The police caught up to him, and then it was the long, dreary slammer for decades, interrupted by a violent breakout in which guards were killed and Barry hid out in the country for three years. Eventually, he was caught and returned to prison. His ever-loyal wife, penniless in his absence and largely shunned from society, visited him. Waited for him. Tragedy ensued: By the time of his release his wife was dead, and he was a man diminished, finding redemption in, at last, ordinary life.