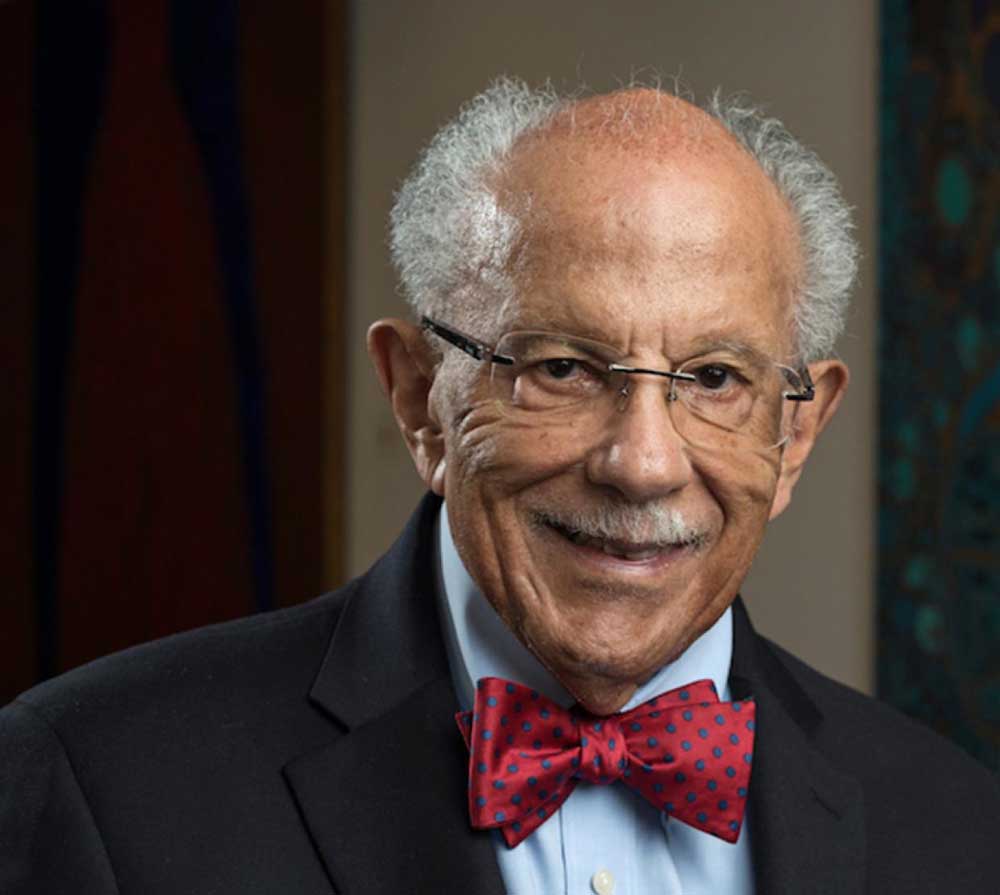

OSU grad who shared Nobel Prize for work on climate change dies at 88

- Warren M. Washington

Published 10:04 am Monday, November 11, 2024

Warren M. Washington, a distinguished alumni of Oregon State University who helped develop one of the first computer models that forecast climate change scenarios and who later contributed to an international research effort that shared the Nobel Peace Prize, died Oct. 18 at his home in Denver. He was 88.

The death was announced by his family and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, where Washington had worked for more than five decades. No cause was noted.

As the warming effects of fossil fuels became increasingly clear, Washington emerged as a prominent voice in efforts to curb human-caused emissions and adjust government policymaking to address climate issues. He advised five White House administrations — some receptive to his research and others less so — and traveled the globe to gather data on climate shifts.

He also carried a historical role as one of the groundbreaking Black scientists in climate-related studies during the 1960s and ’70s when the field was beginning to recognize the potential for rapid changes from greenhouses gases.

“Keep in mind that we’re the first generation that actually sees climate change in human history,” Washington told Business Insider in 2019. “Most climate change has been us going in and out of ice ages over thousands of years. Now we’re seeing things happen over tens of years.”

Washington was studying at Oregon State University in the mid-1950s when he was first inspired to pursue climate science as a student in the College of Science, according to an OSU statement.

Physics professor Fred Decker offered him a weekend job operating a weather radar on top of Marys Peak, OSU said.

This hands-on experience, combined with his education in physics, set the trajectory for Washington’s pioneering work in climate modeling and established the roots of his future achievements in climate science.

OSU is also where he first encountered a computer. The ALWAC mainframe system had paper tape and operated with a series of detailed commands. “You had to be very literal,” he recalled in an oral history with the university.

The computing power, while slow and tedious at the time, showed him the potential for building and analyzing datasets and historical trends. About a decade later in 1964 — working at the National Center for Atmospheric Research — he and a colleague, Akira Kasahara, began work on computerized representations of Earth’s atmosphere. The model gave a hint of the possibilities of using computers to predict the consequences of fossil fuel emissions.

“The early models were simple atmosphere models. Then we added oceans. Then we added sea ice. Then we added land surface vegetation,” he said in an interview for HistoryMakers, a project in which notable Black Americans discuss their life and work.

As technology improved, the enhanced computer modeling reinforced Washington’s belief that rising levels of carbon-based emissions in the atmosphere were driving accelerated changes in climate, including melting glaciers, warming seas and disruption of ecosystems.

“With every successive assessment, the evidence of humankind-caused climate change has become stronger and the science has become stronger,” he wrote in his 2007 autobiography, “Odyssey in Climate Modeling, Global Warming, and Advising Five Presidents.”

Washington’s research also was part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a U.N. study and advisory panel, which shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with former Vice President Al Gore.

“Whereas in the 1980s global warming seemed to be merely an interesting hypothesis, the 1990s produced firmer evidence in its support,” the Nobel Committee wrote in its announcement of the Peace Prize. “In the last few years, the connections have become even clearer and the consequences still more apparent.”

Washington’s studies met with differing receptions in the White House, however. He found support under administrations including President Barack Obama and President Bill Clinton, whose vice president was Gore.

Yet other White House teams questioned Washington’s efforts to elevate climate change on the political agenda. Some of the most sweeping skepticism came from John Sununu, a former New Hampshire governor and Republican who became chief of staff for President George H.W. Bush.

Sununu, who had a doctorate in mechanical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wanted to run the models on his personal computer at the White House. He pressed Washington and his team to make a version that operated with a Compaq desktop.

Sununu incorrectly theorized that the climate models failed to fully account for how oceans can regulate atmospheric temperature, Washington recalled. The dispute came to head during a White House meeting in 1990 with Sununu that included Washington’s colleague Daniel Albritton, the head of the chemistry program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Both Albritton and I said he was wrong,” Washington wrote in an account. Then added: “I think Albritton was more polite.”

In 2016, Washington joined more than 800 scientists in an open letter to President-elect Donald Trump appealing for his administration to back climate change research and alliances.

Trump instead withdrew from the global Paris agreement to reduce greenhouse gases. President Joe Biden rejoined the pact, but Trump’s victory in the 2024 presidential race has revived fears of another U.S. pullout and other moves to undercut climate science.

“Publicly acknowledge that climate change is a real, human-caused, and urgent threat,” said the 2016 letter. “If not, you will become the only government leader in the world to deny climate science.”

Warren Morton Washington was born in Portland, Oregon, on Aug. 28, 1936. His mother was a nurse, and his father worked as a Pullman porter on the Union Pacific Railroad — and helped kindle his son’s interest in science.

On clear nights, they would study the stars and galaxies with a telescope set up on the sidewalk in front of their house, Washington said in a 2015 oral history. At school, he became absorbed in projects of discovery such as investigating how sulfur levels in chicken feed influenced the shades of yellow in egg yolks.

He also served as vice president of the Junior NAACP, giving him a glimpse into the emerging civil rights movement even as he sometimes confronted racism in his own neighborhood. In his autobiography, Washington described his father sitting on the porch with a handgun to “show his defiance” to unfriendly neighbors when they moved into a mostly White area.

At Oregon State University, he received a bachelor’s degree in physics in 1958 and a master’s degree in general sciences in 1960. Four years later, he finished his doctorate in meteorology at Penn State. He already had a job secured at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado.

He became the center’s senior scientist in 1975. A textbook he coauthored with Claire Parkinson, “An Introduction to Three-Dimensional Climate Modeling” (1986), remains one of the standard reference works in the field.

Washington’s awards include the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, widely regarded as the top honor in environment-related work, along with fellow climate scientist Michael Mann in 2019. Obama presented Washington with the National Medal of Science in 2010.

His marriage to LaRae Herring ended in divorce. In 1979, he married Joan Ann Hunt, who died in 1987. Survivors include his wife of 31 years, Mary (née Curtis) Washington; three daughters from his first marriage; and 10 grandchildren.

Apart from the science of climate change, Washington said he saw his mission as part diplomat and ethicist.

“We need to kind of get the countries of the world to agree, instead of just pointing fingers, you know,” he said. “People in China saying, ‘Well you guys caused this problem starting back in 1850 in Europe and the U.S. and we were underdeveloped, and we weren’t putting much CO2 in the atmosphere. Now it’s our turn.’”