Not for web

Published 9:00 pm Tuesday, December 19, 2023

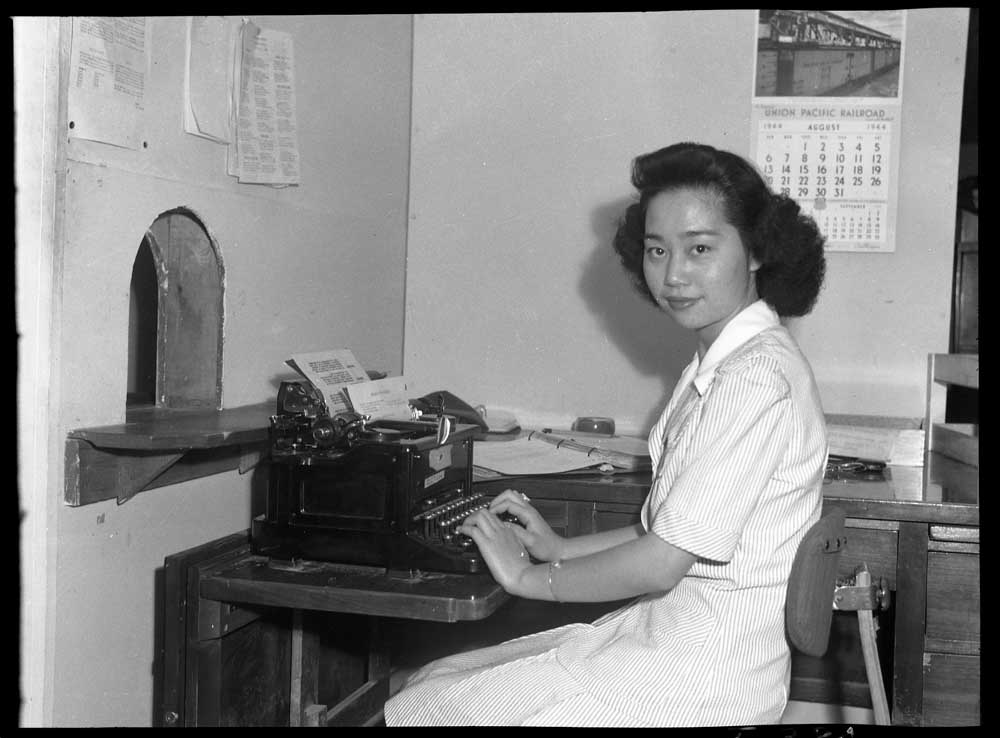

- Mitsuye Endo seated at her desk in the administrative office at the Central Utah Relocation Center.

Many Americans have heard of Fred Korematsu, the Oakland, California, welder who lost his Supreme Court challenge to the banishment and incarceration of Japanese American citizens. But few have heard of Mitsuye Endo. And yet it was Endo’s courageous Supreme Court victory — announced the same day as Korematsu’s defeat — that ended the country’s shameful program.

As we pass the anniversary of both decisions on Dec. 18, it is time to recognize Endo, who died in 2006, and her quiet determination to fight for justice. While Korematsu and other unsuccessful litigants ultimately received the Presidential Medal of Freedom — which they richly deserved — Endo, the lone woman among the Supreme Court litigants and the lone victor, has never received it. President Biden should end this injustice and honor Endo, who won her fight — against all odds, at great personal cost, and with far-reaching consequences.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s notorious Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, gave the military sweeping authority to impose restrictions in geographic areas of their choice — what one military official gleefully called “carte blanche.” FDR did not mention “Japanese” or “Japanese ancestry” in his order. He didn’t have to. Everybody knew it was a response to panicked agitation about Japanese American citizens and Japanese noncitizens on the West Coast. And there was a brazen economic reason. Growers resented Japanese success in agriculture.

Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, a virulent anti-Japanese racist and the military commander for Western states, imposed discriminatory curfews, expulsions from broad geographic areas and indefinite incarceration. Congress criminalized violations of his orders.

The first cases to reach the Supreme Court concerned DeWitt’s criminal curfews, which had led to the convictions of college student Gordon Hirabayashi and lawyer Minoru Yasui. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the discriminatory policy in 1943, ruling that the exigencies of war justified establishing a crime that applied only to American citizens of Japanese descent.

The next year, the court heard the Korematsu and Endo cases challenging the government’s forced expulsion and incarceration. Korematsu had tried to evade DeWitt’s harsh orders, even undergoing plastic surgery in an unsuccessful effort to disguise his ancestry. Once captured, however, he courageously took on the government.

Like Korematsu, Endo was an American citizen, just 21 at the time the executive order was issued. She was fired from her state office job, forced to leave her Sacramento home and incarcerated — all because her parents were from Japan. In July 1942, the shy young typist challenged the United States on this fraught wartime issue.

The federal government acknowledged that Endo posed no security risk but still refused to free her. The military, however, concerned about her litigation, offered to release her if she would agree not to return to California. Endo refused.

The court rejected Korematsu’s challenge to his forced expulsion, blithely stating that “hardships are part of war.” Today, the decision ranks with Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson as among the worst ever issued. But in Endo’s case, the court concluded that neither FDR’s executive order nor the congressional statute authorized the continuing imprisonment of a citizen, after almost three years, whose loyalty had been established.

Mitsuye Endo had won a historic victory. Even here, however, the Supreme Court acted cravenly. At least one justice, generally thought to be Felix Frankfurter, apparently tipped the government about the pending decision. The day before the court’s Endo announcement, the military announced the end to the banishment policy as well as the lifting of all restrictions on any individuals found loyal. When the Supreme Court announced the decision, it was anticlimactic. But Endo, the unassuming young woman who refused freedom to continue her battle, had been the catalyst for an end to the abominable policy.

All three branches of the federal government ultimately repudiated the anti-Japanese policy. In 1976, President Gerald Ford formally revoked FDR’s order, calling it “a sad day in American history.” In 1988, Congress passed a reparations bill. And, in the Supreme Court’s 2018 opinion upholding President Donald Trump’s travel ban, justices on both sides, bitterly divided on most issues, agreed that Korematsu was “gravely wrong the day it was decided.”

From 1998 to 2015, Presidential Medals of Freedom were awarded to Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi (posthumously), and Min Yasui (posthumously). Only Mitsuye Endo has never received the honor. It is high time to celebrate her contributions to justice and the rule of law.

Poet Amanda Gorman wrote, “There is always light / If only we’re brave enough to see it / If only we’re brave enough to be it.” Endo was brave enough to see the light — and brave enough to be the light. Her little-known saga is an enduring inspiration.