Not for web

Published 9:00 pm Friday, December 1, 2023

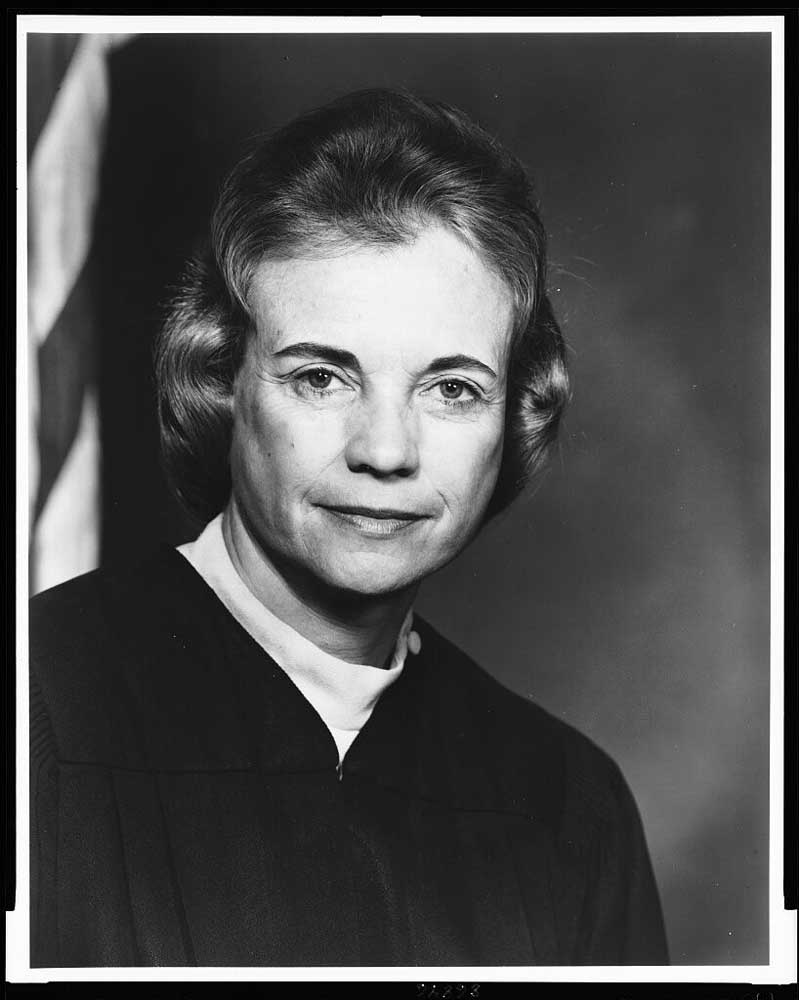

- Sandra Day O'Connor in 1995.

When Sandra Day O’Connor first arrived at the Supreme Court in the fall of 1981, she found it to be a cold place. The other justices were not entirely welcoming to the first woman in their midst. At her first lunch with the justices, half of them did not show up. At her investiture, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger paraded the newly robed O’Connor down the court’s front steps, exclaiming to reporters, “You’ve never seen me with a better-looking justice.” She smiled gamely; she was used to this sort of thing.

Over the course of her long ascent from ranch girl to the first female justice on the Supreme Court, she had come to understand that self-restraint and civility would make her more, not less, powerful.

As a new justice, O’Connor soon bonded with Lewis F. Powell Jr., a courtly gentleman who enjoyed dancing the fox trot with her at Washington social events. She felt a bit cold-shouldered by her fellow Arizonan, Justice (and later Chief Justice) William H. Rehnquist, who, unbeknownst to the other justices, had proposed marriage to his law school classmate and moot court partner Sandra Day in 1952. (The other justices knew only that the two had “gone to the movies.” Still, when O’Connor came on the bench, Harry A. Blackmun teased Rehnquist, “Now, no fooling around.”)

O’Connor, who died Friday at age 93, had a strong ego, and she could be, to use her word, “bossy.” She relished putting together majorities in close cases; her husband, John, wrote in his diary that it made her feel “like she was in the catbird seat.” But she never showed off, and she knew when to let others take the glory. She was initially assigned the majority opinion in U.S. v. Virginia, the landmark case giving women the right to attend Virginia Military Institute and other formerly all-male public institutions of higher learning. In an act of self-abnegation unusual among justices, she demurred. “I think this should be Ruth’s case,” O’Connor said, because Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who had come to the court 12 years after O’Connor, had devoted her career to women’s rights. “I loved her for that,” recalled Ginsburg.

O’Connor’s law clerks were sometimes intimidated by her no-nonsense approach to work and life, but most of them came to revere her. “She was actually modeling a balanced life,” said Lisa Kern Griffin, now a Duke Law School professor. “Make time for your family. Take care of yourself. Experience the outdoors and get some exercise. Have a sense of the wider culture. Enjoy lively dinner parties and a varied circle of friends. Never be above taking care of people. It was really unusual. We were getting not just an apprenticeship in law but an apprenticeship in life.”

A Supreme Court law clerk can get easily swept up in the rivalries between the justices. Antonin Scalia could be caustic, once writing that O’Connor’s opinion in an abortion case “cannot be taken seriously.” But whenever one of her clerks tried to snipe back at Scalia with a clever line in a draft opinion, O’Connor cut it out. She never carried grudges; she moved on. Her worst criticism of anyone, her husband noted in his diary, was: “He has a pretty high opinion of himself.”

But when she chose to make a stand, she could be direct. As majority leader of the Arizona state Senate in the early 1970s, she confronted a lawmaker named Tom Goodwin for being a drunk. He snarled, “If you were a man, I’d punch you in the nose.” O’Connor responded, “If you were a man, you could.”

O’Connor, who cast the decisive vote in 330 cases over 24-plus years on the court and wrote the controlling opinions on major social issues such as abortion and affirmative action, understood that power and influence should be wielded with good humor and decency. When Clarence Thomas arrived at the court in 1991, he felt lonely and isolated — “hammered,” as he put it, by his confirmation hearings. After the court’s conferences, O’Connor began walking with him back to his chambers, saying, “You should come to lunch.” Thomas sulkily resisted. But “one day,” he recalled, “she looks at me, ‘Now, Clarence, you need to come to lunch!’” Thomas laughed as he recalled the scene. “So then I said, ‘Yes, ma’am!’” Thomas soon learned that O’Connor made all the justices come to lunch. “She was the glue,” said Thomas. “The reason this place was civil was Sandra Day O’Connor.”