Jails across Oregon struggle to treat substance use disorders amid funding challenges and medical staff shortages.

Published 5:45 am Sunday, November 26, 2023

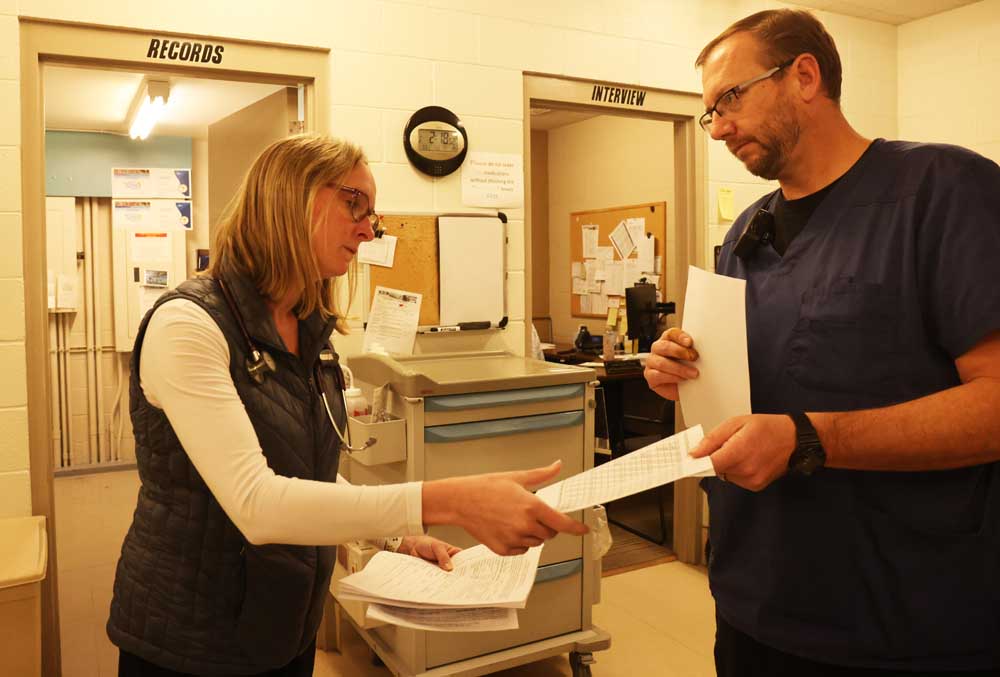

- Eden R. Aldrich, Deschutes County Sheriff's Office nurse practitioner and medical director, left, works with Jonathan Handschuch, a corrections nurse at the Deschutes County Jail in Bend.

Erick Kelly had one month remaining in his sentence for theft at Deer Ridge Correctional Institution in Madras, when a member of the medical staff offered him suboxone, a once-a-month injection prescribed to treat opioid addiction.

Most everyone in his family struggled with substance abuse, and for the first time in the isolation of a 23-hour prison lockdown, Kelly grieved over his father’s death triggered by drugs and alcohol. He wanted to be more present in his own son’s life and decided to get sober.

Trending

Kelly was at first reluctant to accept the suboxone injection.

Now, he fully credits the medication he received at Deer Ridge with saving his life. Only a small percentage of Oregon’s prisoners have similar treatment opportunities, and these programs are typically restricted to inmates nearing their release date, like Kelly.

Despite mounting pressure from Oregon legislators Rep. Maxine Dexter, (D-Portland) and Rep. Pam Marsh (D-Ashland) and a federal court ruling that determined correctional facilities cannot deny access to medications used to treat addictions, less than half of Oregon’s jails and prisons provide drug treatment programs due to budget gaps and shortages in qualified medical professionals.

Research shows Oregon ranks among one of the worst states for substance use and mental health problems, while it’s simultaneously the lowest in health care access for the state’s residents, according to a 2022 report from Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission. These circumstances are often exacerbated within correctional facilities. It’s estimated that anywhere between 50% to 70% of all adults in-custody could benefit from a combination of behavioral health and substance use treatment.

“I would say that everyone who experiences addiction needs some form of mental health treatment. You can take away the substance all day long and we still have issues to address,” said Heather Daugherty, an outreach coordinator at Ideal Option.

“Trauma is the gateway drug.”

Trending

Deschutes County Jail

Deschutes County Jail partnered in June with Ideal Option, a national addiction treatment provider that offers medications and behavioral health services. Ideal Option’s partnership with the jail is funded by Measure 110, and thus far, has helped treat 49 adults at the jail, Daughtery said.

Medically-assisted treatment, like methadone or buprenorphine, historically, has not been widely available in correctional facilities. These medications, some of which have been used since the ’60s, function by blocking opioid receptors in the brain, can lessen physiological cravings and prevent the euphoric effects of opioids like heroin and fentanyl.

While these medications are FDA-approved and widely recognized as the gold standard for the treatment of addiction, they are themselves opioids and can be misused.

Treating jail inmates for addiction in Oregon is a facility-by-facility decision, one that is largely dependent on that county’s resources.

Drug overdose deaths are soaring in Central Oregon

Around half of Oregon’s 36 jails self-report temporarily providing medications that can alleviate the risk of fatal seizures, or ease the severe symptoms that can last over a week into withdrawl.

The anxiety, nausea, vomiting, cold sweats, diarrhea and body aches can be so excruciatingly painful that it’s not uncommon for those detoxing to have suicidal ideation, said Michael Shults, a Deschutes County Jail captain.

Many jails will also allow an inmate to continue accessing medication if they have a prescription prior to incarceration.

A federal court ruled in 2018 that a jail’s blanket prohibition of medically assisted treatment violated the Americans with Disabilities Act and was inconsistent with inmates’ constitutional right to health care. Fearing potential lawsuits, more and more correctional facilities have since allowed inmates to access treatment. Still, only a handful of states have passed legislation requiring jails and prisons to offer these medications. Oregon is not one of them.

The assertion that adults in-custody have a legal right to substance use treatment while in jail is a relatively new concept, at least in Oregon, said Tara Herivel, an attorney that specializes in representing prisoners in medical malpractice lawsuits.

“I’ve never had a client in a jail setting who got any kind of treatment, or a case where somebody was asserting that they had a right to drug treatment and that they were being deprived of it. But they sure should, because that would absolutely fit,” Herivel said.

Kelly said he never received withdrawal or opioid treatment medications while booked in an Oregon jail. There are also no statutes that outline a process for adults in-custody to pursue a review of their health care needs if they believe a jail is not adequately addressing them, according to the recent report from Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission.

“When I was detoxing off fentanyl, I was sick in jail for 21 days. I couldn’t move out of bed,” Kelly said. “They wouldn’t even give me ibuprofen.”

The new partnership comes at a time when overdose fatalities are spiking across Central Oregon and officials are concerned over the emergence of xylazine, a tranquilizer meant for animals like horses or cattle. Xylazine, also known as “tranq,” surpasses fentanyl in potency, is resistant to Narcan and can cause visible open flesh wounds across the body.

From 2019 to 2022, unintentional opioid overdose deaths rose 241% across the state, according to the most recent data from the Oregon Health Authority. That same data shows that 18 Oregonians died every day from opioid overdoses in 2022.

While Oregon’s effort to decriminalize illicit drugs was meant to divert those with substance use disorder away from the criminal justice system, it’s not uncommon for people to be arrested for offenses adjacent to their addiction, like theft or drunk driving. As the state’s opioid crisis worsens, jails are tasked with remedying mental illness.

“The majority of what I do on a daily basis is mental health,” said Eden Aldrich, the medical director for the Deschutes County Sheriff’s Office. “Anxiety, depression, bipolar [disorder], schizophrenia and psychosis; and much of it is exacerbated by substance use, especially in our severely mentally ill.”

The consequences of not receiving behavioral health and substance use treatment can be fatal, too. Over 300 people died while in-custody of an Oregon or Washington jail from 2008 to 2018, according to an OPB investigation. Among cases where the cause of death is known, almost half were attributed to suicides. Three people died as a result of dehydration during withdrawal, an outcome that can be prevented by providing gatorade or other electrolytes.

“When you’re in jail, you’re feeling so alone and scared,” said Shawnda Jennings, a peer outreach specialist at Ideal Option. “You feel that no one’s there for you. A lot of times people are suicidal. It’s a fight for people’s lives,”

As more illicit drugs are smuggled into correctional facilities during intake procedures, these medications could play a role in limiting overdose deaths.

In January, six adults at Deschutes County Jail were resuscitated with Narcan after overdosing on fentanyl. Kelly said he witnessed one of his best friends die from an overdose in-custody after jail staff denied his request to go to a hospital. Kelly knows around 20 people that have died from drug-related causes.

“I didn’t care who I hurt, I didn’t care what was going to happen. I was going to use drugs no matter what,” Kelly said. “Even though I overdosed so many times, I still didn’t think that I would ever die, and sometimes I didn’t care.”

Funding challenges

Regardless of their conviction status, an adult will lose their medicare coverage within 24 hours of entering a jail. Many medical professionals describe this sudden interruption of coverage as needlessly rash and redundant, as it hinders high-risk adults from accessing consistent care and shifts the burden of high medical costs onto the jail.

How has Measure 110 changed drug treatment in Deschutes County?

“We’re detoxing people, and finally, for the first time, they’re clear headed. They’re needing treatment for their hypertension, or their mental illness or their diabetes that they didn’t even know they had. But yet we’re giving them no resources,” said Aldrich. “Their medicare, medicaid, VA benefits have all been suspended. Why are we taking medical benefits away from people who are innocent until proven guilty?”

And without health care coverage, treatment can become wildly inaccessible. While a daily buprenorphine prescription may cost the jail a few dollars a pill, a monthly buprenorphine injection known as Sublocade costs $1,500 per vial.

For some, injections tend to be preferred over daily medications, Jennings said. If someone is tempted to relapse, simply skipping a day or two of their pills can be enough to eliminate the opioid receptor-blocking effects of the medication. However, with an injection, there’s a built-in failsafe.

The medicine is gradually released throughout the body over a month, and it becomes more challenging for individuals to relapse.

Ideal Option is one of the six service providers across Deschutes County that received $11.5 million in Measure 110 funding for substance use treatment, housing and harm reduction programs. Ideal Option was granted around $1.17 million.

Shortages of health care professionals

Despite Bend’s rapid growth in recent years, Deschutes County Jail faces budget restrictions and shortages in the qualified medical staff that are crucial to support these treatment programs. Droves of nurses retired following the COVID-19 pandemic, Aldrich said, and it’s hard for the jail to compete with the salaries offered by St. Charles Bend.

“We’re down six nurses. There’s only four nurses right now that are taking care of the most vulnerable people in society,” Aldrich said. “We see dozens of patients a day [and] do several hundred sick call visits a month. My nurses work twice as hard as I do.”

Without drug court in Deschutes County, where do people go now?

Other jails aren’t so lucky as to have a medical professional on-site at all times, and it’s this lack of health care infrastructure that prevents many smaller jails from offering treatment. One small jail in southern Oregon has a retired nurse that volunteers a couple days a week, said Bridget Budbill, a senior policy analyst at Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission.

“I think treatment programs will help our whole correctional system. We are one of the few jails that have started up a [medically assisted treatment program] in our state. I know the other jail managers are struggling to do that,” said Capt. Shults. “Jails should be expensive. We’re dealing with the most vulnerable people.”

Daugherty, almost 12 years sober herself, is determined to introduce treatment programs into county jails and state prisons across Oregon.

“My goal is to hit every single county jail,” Daugherty said, laughing. “You can’t tell me no. I’m just gonna go to every single one. I’ll do it off the clock.”

Reintroducing legislation

Rep. Maxine Dexter, herself a pulmonary and critical care physician, plans to reintroduce a bill in 2024 or 2025 that would require that behavioral health and medically assisted treatment be made available to all eligible inmates in state prisons. For Dexter, this legislation will help ensure that Oregon fulfills its responsibility to provide adults in-custody with their constitutionally protected right to healthcare.

Her bill, HB 2890, received unanimous support in the House Judiciary Committee in 2023, but failed due to a lack of funding.

“Some of the data that we received showed that only 9% of people who qualified for substance use disorder treatment in prisons were able to receive it,” Dexter said.

Rep. Pam Marsh sponsored House Bill 3391, legislation that would have strengthened health care standards and expanded oversight inspections in jails. That bill died, too, when it didn’t get scheduled for a work session.

Now, former inmate Erick Kelly and the lives of his family are no longer dictated by substance abuse. His mother is nine years sober and his sister recently entered detox.

“Substance use disorder is a chronic disease, and we should be obliged to treat any chronic disease for people in our custody when we take away their rights to care for themselves,” Dexter said. “It is upon us to care for them. Somehow we see substance use disorder as different. And that needs to change.”

Oregon lawmakers prep to tackle drug addiction in 2024 session