Summer brings COVID-19 uptick

Published 2:26 pm Friday, July 28, 2023

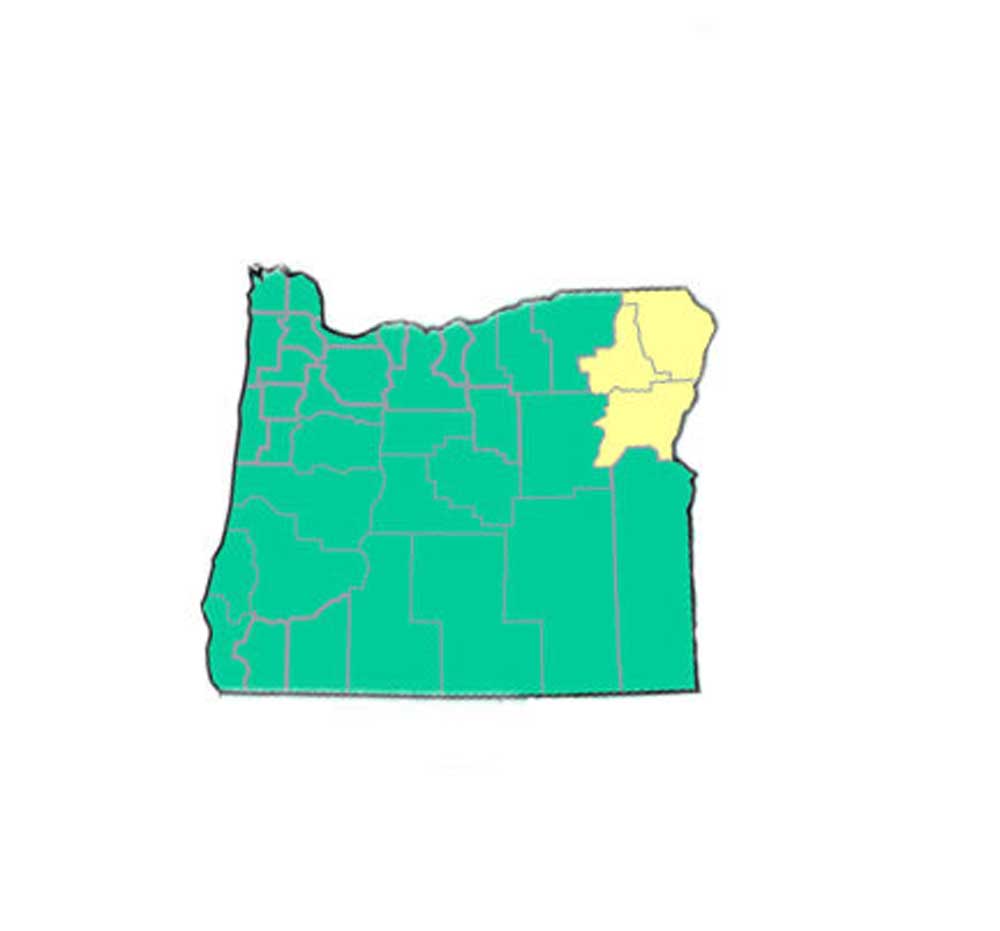

- All but three Oregon counties had a low per-capita COVID-19 new hospital-admission rate for the week ending July 22. Baker, Union and Wallowa counties had medium per-capita rates that week, according to the CDC.

Summer has brought an uptick in coronavirus transmission, but experts say it is still too early to tell whether the upswing represents a significant public health concern.

The U.S. recorded a 12% increase in new COVID-19 hospital admissions for the week that ended July 22 compared with the previous seven-day period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Still, hospitalizations remain near a record low for the pandemic.

Hospitalizations are rising fastest in the South, Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states. California, so far, has fared better.

For Oregon, CDC data shows Wallowa, Union and Baker counties with a medium rate of new hospitalizations ending the week of July 22, between 10 and 19.9 per 100,000 people. The agency reported Oregon’s other 33 counties at the low rate, less than 10 admissions per capita.

“There’s no doubt compared to our (lowest points), or the stability that we’ve enjoyed, that there’s a slight increase in test positivity,” Dr. Mark Ghaly, secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency, told The Times in an interview.

“And the question is going to be: How sick do people really get, now that we’ve had a degree of immunity?” he said.

The extent of the increase in transmission is difficult to quantify. Official case counts are now largely unreliable due to the proliferation of at-home testing and reduced data reporting.

Experts and officials say it’s not surprising that a summer coronavirus uptick has arrived, given seasonal patterns in recent years.

Travel has also roared back from pandemic-era lows. The Transportation Security Administration recently said that, nationally, June 30 was the busiest day ever for the agency’s operations, exceeding the previous record set on the Sunday after Thanksgiving in 2019.

And as vacations and conferences return, with most people having shed masks, chances for infection have increased.

Timing also plays a role. Most people are well removed from their last COVID-19 booster shot and, given that the most recent coronavirus uptick occurred last winter, it’s probably been months since many were exposed to significant circulation of the virus.

“This comes at a time when people’s collective immunity is waning,” said University of California, San Francisco, infectious-disease expert Dr. Peter Chin-Hong. “So it’s kind of like the force field is weaker, so to speak.”

The U.S. reported 8,035 COVID-19 hospital admissions for the week that ended July 22, the most recent for which data are available. That’s slightly up from the pandemic record low of 6,294, which was set during the week that ended June 24.

The national hospital peak came the week that ended Jan. 15, 2022, during the height of the first omicron surge. In just that seven-day period, there were 150,674 COVID-19 hospital admissions.

In 2022, COVID was L.A. County’s third-leading cause of death, behind heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. But “based on death numbers to date,” the county Department of Public Health said in a statement, “we anticipate a significant decrease in the ranking of COVID-19 this year.”

“Looking at the current patterns we are seeing between cases, hospitalizations and deaths provides evidence that built-up immunity, through vaccination and prior infections, is likely leading to greater resilience against severe illness,” county Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said in a statement. “With vaccines and therapeutics remaining effective against the circulating strains of COVID-19, we can take comfort knowing that COVID is now something we can manage.”

That deaths haven’t started to increase nationally could be explained either by the traditional lag or, more optimistically, by lower mortality rates, Chin-Hong said. It could end up being the case, he said, that while COVID-19 patients might still seek emergency room care, fewer will need to be admitted into the hospital and far fewer still will die.

However, it remains possible COVID-19 could pose a larger problem in the winter, Chin-Hong said.

Officials say people should still take prudent steps to avoid infection, such as avoiding sick people and getting tested if you have COVID symptoms. Keeping a mask handy so you can wear it if needed — for instance, if you’re unlucky enough to sit on a plane next to coughing people spraying droplets in your face — would also be a good idea.

The rise in viral transmission will increase the risk of people being exposed to someone who is contagious. Chin-Hong said he’s heard of a number of people who have never had COVID-19 before who are getting it now.

“If you have more people transmitting stuff around — and particularly if few people are testing — then people who haven’t gotten it before will continue to get it,” he said. “Many people will do well, but some of those people, statistically speaking, won’t.”

Aside from the chance of serious illness, some people may go on to develop long COVID — the umbrella term for a long list of symptoms that can endure months or years after an infection.

Now that Paxlovid, an anti-COVID oral drug that can be taken after infection, has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, higher-risk people can talk to their health care providers about getting Paxlovid in advance of, say, an overseas trip if they think it’ll be hard to obtain the drug later. That would enable people to take the pills quickly should they test positive for the coronavirus, Chin-Hong said.

It can be helpful to have the Paxlovid conversation in advance of becoming sick with COVID-19, Chin-Hong said. That way, patients can talk with their regular health care providers about the possibility of interactions with other drugs they are taking.

The FDA says Paxlovid significantly reduces the percentage of people with COVID-related hospitalization or death from any cause.

People who come down with COVID symptoms or test positive for the virus should isolate for at least five days after their symptoms begin or after they first test positive, whichever comes first, health officials say.

According to the L.A. County Department of Public Health, COVID patients can generally exit isolation after the fifth day, provided their symptoms are mild and improving and they don’t have a fever. The agency does recommend, however, that people wait until they test negative if exiting isolation before 10 days are up.

County health officials also suggest wearing a mask when near other people for 10 days after the onset of symptoms or their first positive test. But they also say residents can stop masking after the fifth day if they meet the criteria to end isolation and have two negative COVID-19 test results in a row, taken at least a day apart.

Isolation and mask wearing can generally end after the 10th day, without the need of a negative test result. But people who still have a fever should stay isolated for at least a day after the fever ends. People who are immune-compromised or have severe COVID-19 should speak with a doctor about when they can be around others.