New normal for child care providers includes new illnesses, new growth and newfound appreciation

Published 5:00 am Thursday, January 12, 2023

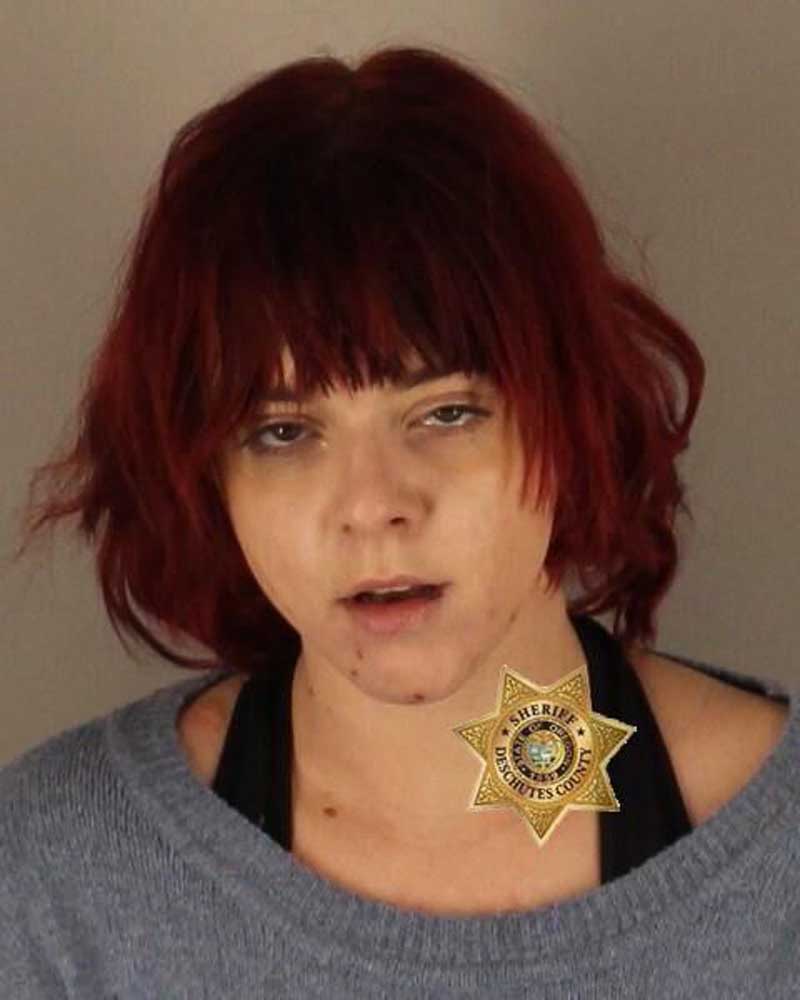

- Lisa Christensen, a teacher for children up to a year old at Bloom Children's Center in Bend, interacts with children at the center on Dec. 15. The pandemic has added work for the staff at center.

The pandemic presented two options for Stephanie Krause’s business: Close, or expand.

She chose the latter, growing her preschool into a larger number of small classrooms instead of remaining in the larger classrooms that would have — due to pandemic distancing requirements — forced her to hire more staff than she could afford.

But now, she and her staff at Bloom Children’s Center in Bend have found their new normal is more work than ever, Krause told The Bulletin.

“I think that early childhood educators … they’re having to do all the same jobs they used to and yet we’re still — especially this winter with all the incredible rates of illness that are around — there are extra things that we have to do all the time,” Krause said.

That workload has grown throughout the pandemic as child care providers have shuttered and the demand for care has persisted. For child care providers like Krause, the pandemic has created a host of new challenges and changes, from different behavior to different illnesses.

While COVID-19 is slightly less of a concern than it used to be at the outset of the pandemic, the impact that a year in isolation had on immune systems is still visible in Bloom classrooms.

On the mid-December day Krause spoke to The Bulletin, for example, half of the children her staff cares for were out sick, caught in a nationwide wave of illnesses like the flu and respiratory syncytial virus, also known as RSV.

“I just feel really sad for parents because I absolutely understand that many parents feel like their child is just almost never attending care,” Krause said.

The pandemic’s isolation has also had an impact on the development of the children Krause serves, she said. But, while K-12 teachers have reported behavior and attendance issues in students since the pandemic, early childhood educators have the advantage of working with children at a more flexible point in their development, despite most of their lives having been in the pandemic.

So while Krause and her staff might see a 2- or 3-year-old unable to recognize social cues or interact with a lot of other people because of the pandemic’s social isolation, “they learn that really quickly at this age.”

As in many parts of society since the pandemic began, more extensive cleaning and disinfecting have also become second nature for Krause and her staff.

Containing an illness among children is harder than in an adults. An office cubicle or an office separated by a hallway can help limit exposure among adults, Krause said.

“Whereas children are literally in each other’s spaces, on each other and on their caregivers, and so it’s just a different thing,” she said.

Krause counts at least one thing as a positive element of her new normal: An increased appreciation for the work of early childhood educators.

“What I feel that I’m experiencing is that the families that are grateful for care are more grateful for care than what I’d experienced historically,” Krause said. “They recognize how hard we’ve worked where, prior to the pandemic, I don’t know that that was in the light as much.”