Enrollment plummets at most Central Oregon public schools this year

Published 2:00 pm Saturday, February 6, 2021

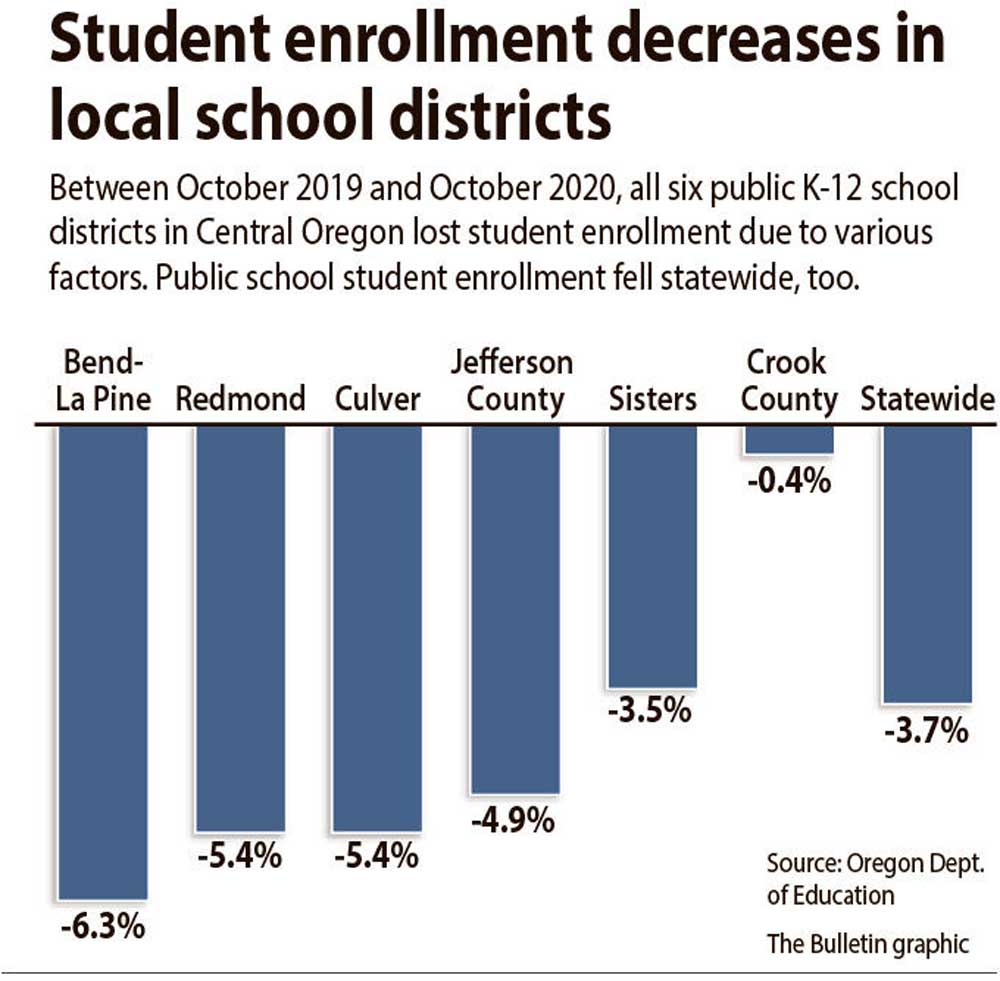

- Student enrollment decreases in local school districts

Enrollment in Central Oregon’s public school districts plummeted this school year. Bend-La Pine Schools and Redmond School District lost more than 1,500 students combined.

Meanwhile, enrollment in private and online charter schools skyrocketed, the number of local students being homeschooled has spiked, and many parents of younger children have opted to postpone starting school all together.

The overarching theme of this massive shift in enrollment is that many parents had no interest in traditional schooling during COVID-19, with distance learning, constantly changing re-opening plans and post-reopening safety concerns.

“We just wanted a school year where we didn’t have to be yanked around,” said Kristina Johnson, a Bend parent who moved her third grader from Lava Ridge Elementary to Bridge Charter Academy this fall. “We were (also) reasonably concerned about the risk of COVID transmission to us, and to our grandparents who moved next to us to be near kids.”

Between October 2019 and October 2020, all six Central Oregon K-12 school districts saw a drop in enrollment, according to state data released Thursday. The biggest drops, by percentage, happened at Bend-La Pine Schools, at 6.3%, and Redmond and Culver school districts, each with 5.4%.

Crook County School District had easily the smallest dip, only losing 0.4% of its student population, or 11 students. And since October, the Prineville-based school district has added 53 more students, according to Superintendent Sara Johnson.

Statewide, public school enrollment, including charter schools, fell by 3.73%.

Where did the students go?

Statewide and local education officials have various theories as to where public school students wound up.

One big culprit is homeschooling.

This school year, the High Desert Education Service District — a Redmond-based agency that, among many other educational duties, registers local families for homeschooling — saw a sharp increase of homeschoolers.

Since September, 803 local students signed up for homeschooling, compared to 131 last school year, service district spokesperson Linda Quon said.

Although High Desert ESD doesn’t ask parents why they choose to homeschool, it’s assumed that many did so to avoid public school distance learning, Quon wrote in an email.

Some local private schools also saw a population boom, as their smaller size allowed them to reopen faster than big public schools, where in-person learning has only resumed in the past few weeks.

Trinity Lutheran School in Bend saw a slight decrease in enrollment in September, as families weren’t sure if the K-12 private school would be fully in-person, said Head of School Gregg Pinick.

But all students were fully back by the start of the second semester on Jan. 19. In response, Trinity Lutheran’s enrollment jumped by 50 students that day — requiring the school to open second classrooms in kindergarten, first and second grades, Pinick said.

“The pandemic has really been an accelerator for our school,” he said.

Seven Peaks School and Cascades Academy each had to stop accepting new students this year due to increased demand.

Seven Peaks’ enrollment dramatically increased in September, with 56 new students, said Tracy Jenson, director of admissions.

Every classroom, from preschool through eighth grade, is filled to state-mandated social-distancing capacity. Some parents have even burst into tears trying to get their child in, Jenson said.

“It’s been the busiest enrollment experience I’ve ever experienced,” said Jenson, who’s led enrollment at Seven Peaks for three years. “I feel like I need to duplicate myself.”

Public charter schools — many of which specialized in online or home-based learning before COVID-19 forced traditional schools to do so — also saw a boom in enrollment in 2020.

Three of Oregon’s four largest public schools are now charters: Oregon Charter Academy, Oregon Virtual Academy and Baker Web Academy, which each added hundreds of students this school year.

One of those charter schools — Bridge Charter Academy, which has campuses in Bend and the rural Eugene suburb of Lowell — more than doubled its enrollment in 2020, from 367 students to 778. This was a mixed blessing, said Principal Ben Silebi.

“On one level, it was great to see enrollment going up … but it was a very terrible summer for our employees,” he said. “We had 12-hour-days trying to keep up with enrollment.”

Silebi said he believes Bridge Charter saw increased enrollment because it is better at teaching students at home compared to traditional school districts.

“We heard over and over from families that they wanted to get into a program that had some experience in that area, instead of a half-baked education,” he said.

And many families of young children, particularly kindergarteners, chose to wait to start school. Statewide, 28% of the public school enrollment decline came from kindergarten enrollment, said Jon Wiens, director of accountability and reporting for the Oregon Department of Education.

Charan Cline, superintendent of Redmond School District, confirmed there were big drops in kindergarten and first grade enrollment for his schools. And he doesn’t find that too concerning.

“It’s not necessarily damaging to a child to wait an extra year to wait until you start kindergarten,” Cline said. “I did that with my younger child. They’ll catch up.”

How does this affect public schools?

Financially, this COVID-19 enrollment dip shouldn’t hurt local schools too much — as long as a majority of these students return.

The state calculates school funding based on enrollment over a two year period. Funds are awarded based on the larger year. So most school districts will be funded based on their 2019-20 school year population, said Wiens.

Cline said he expects attendance to bounce back, at least partially, in September. But the influx of kindergarteners who waited a year — plus a new crop of kindergarteners — could create an enrollment bubble. That means school districts will have to serve one class of students much larger than the others for 13 years, he said.

“If we have 300-400 kids in a grade level, but there’s a year with 500 kids in a grade level, that causes us to shift staff all over the place,” Cline said.

And although some younger students who’ve stuck with traditional public schools have smaller class sizes, that doesn’t guarantee a better educational experience this year, Cline said.

“Distance learning is really weird,” he said. “Some (kindergarteners) are doing well with it, some are really not doing well.”