52 years later, Oregon’s oldest half marathon is still going strong

Published 12:00 am Monday, May 21, 2018

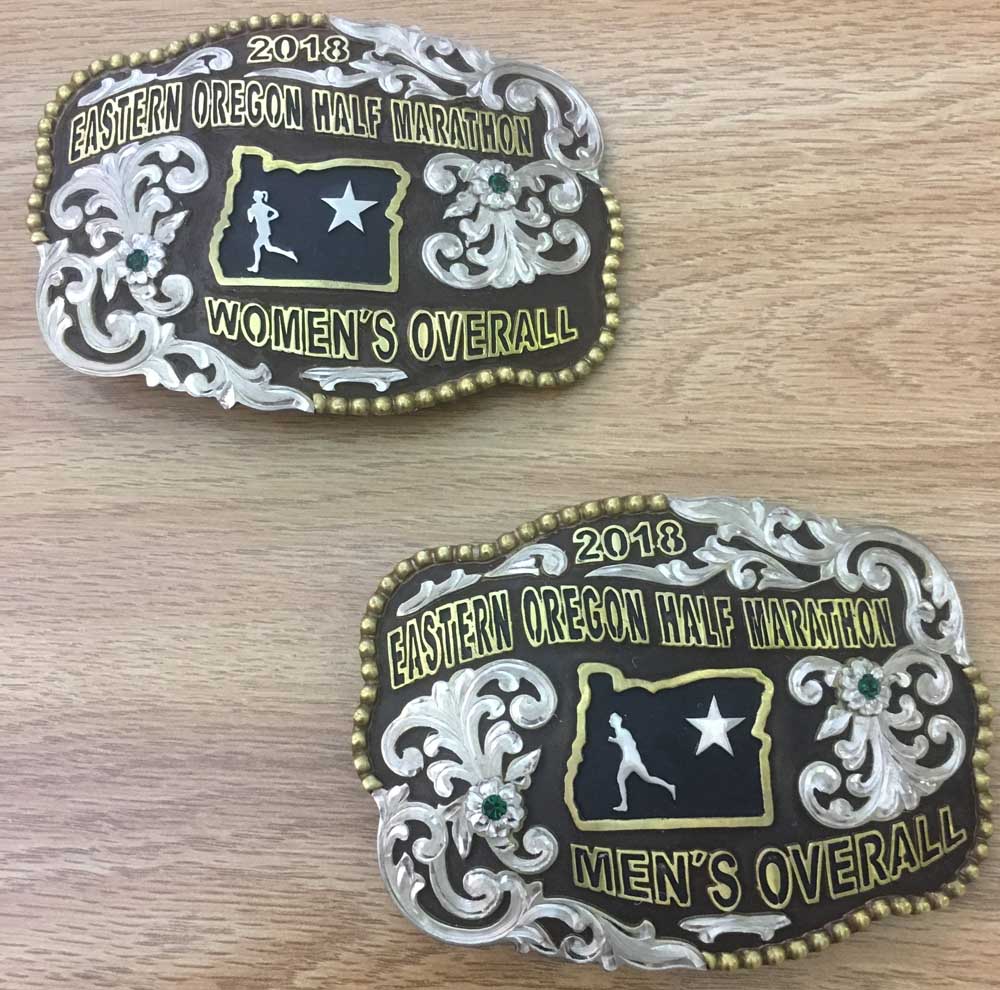

- Belt buckles that will be awarded to the men's and women's winners of the Eastern Oregon Half Marathon on Saturday. (Submitted photo)

PRINEVILLE — Back in 1965, Lyle Rilling was not much of a runner. Neither was Tom Nash, then the school superintendent in Spray, who that spring challenged Rilling to a race from their tiny farming town to Service Creek, an even tinier community about 13 miles down the highway.

For that matter, there were not many runners at all in Wheeler County in the 1960s.

“In those days, if you were out running on the road, people would stop and say, what’s wrong? Can I help you?” said Rilling, now 77, who retired to Prineville after 33 years as a school administrator. “Today, you see runners all the time. But in those days, especially in that rural country, they’d ask, did the horse throw you off? They just didn’t see anyone running on the road.”

On that spring morning in 1965, as Rilling and Nash raced to Service Creek, they could have used the help of a passing motorist.

“We bet breakfast, but (by the end) we didn’t feel like eating, I can tell you that,” Rilling recalled. “We were both sick. Legs were swollen up, bloody, because back in those days the shoes we wore were nothing but Converse basketball shoes. It was pretty rough.”

They finished the run together after more than two hours, then soaked their aching legs in the John Day River, which runs along Highway 19, as they waited for Nash’s wife to pick them up. Despite the shinsplints and lost toenails, Rilling decided he wanted to try the run again. And next time, he wanted to invite more people.

The first official Eastern Oregon Half Marathon, which was sponsored by the Spray School student body and attracted five runners, was run in spring 1966. The distance between Spray and Service Creek along the two-lane highway that flanks the river just happened to match the 13.1-mile length of a half marathon, an event that was only beginning to emerge in the mid-1960s.

(The oldest continually run half marathon in the United States, according to halfmarathons.net, is the Lincoln Presidential Half Marathon in Springfield, Illinois, which was run for the first time in 1964.)

By the third year, the format of the Spray race had taken its current shape: The race would be run on the Saturday of Memorial Day weekend in conjunction with the Spray Rodeo. The direction of the run was reversed from Rilling and Nash’s original route, so runners would start in Service Creek and finish in Spray in time for the rodeo parade.

Within a few years, the race had developed a bit of a reputation among Oregon runners. For one thing, it was fast: Most of the entrants were young men who ran for their high school or college track teams (according to early results sheets, the “senior division” included runners 26 and older). With so few road races of comparable distances held in the Northwest, many competitors made the most of the race to Spray: John Woodward beat out a field of 17 runners with a time of 1 hour, 7 minutes and 55 seconds in 1969, and Gary Purpura, who won the race five times between 1968 and 1980, set the still-standing course record of 1:06:34 in 1975. (To put that time into context, the fastest half marathon recorded anywhere in the world in 1975 was run by West Germany’s Paul Angenvoorth in 1:05:08.)

But the race was just as well-known for being wild. As is still the case today, most runners traveled from outside the area to compete, but Spray’s remote location — about an 80-mile drive northeast from Prineville — and lack of lodging led most entrants to leave for the race in the middle of the night or camp out in Spray or Service Creek the night before. According to a 1973 article in the (Eugene) Register-Guard, the Spray Rodeo Association allowed runners to stay in the Grange Hall for free the night before the race, so long as they did not mind sharing the space with dozens of rowdy rodeo cowboys who had no intention of sleeping the night before their events. (The runner interviewed by the Register-Guard did mind.)

“You kind of have to make a weekend out of it,” said John Wagner, a Prineville resident now in his second year as race director. “It’s not a race where you wake up in the morning, go downtown and run, and you’re home for lunch. It’s really a full-day deal.”

Peter Hatton would often make the trip from Bend with his dad, Raymond Hatton, who won the race four times between 1970 and 1974.

“We’d go over there the night before and stay in a motel in Fossil (more than 30 miles west of Spray), and watch my dad race,” said Hatton, who was a teenager at the time. “Typically, there weren’t too many competitors back then, but it was always a wild time in Spray that afternoon. We were told it was best not to camp in Spray if you wanted a full night’s sleep. I don’t know if that’s changed or not.”

There were also natural hazards for runners and spectators to be wary of, namely rattlesnakes.

“The course winds along the John Day River, and there were times you had to watch where you stepped,” Hatton recalled. “There were rattlesnakes on the side of the road, and sometimes on the pavement. They liked the hot pavement.”

Hatton said his father, a longtime Central Oregon Community College professor and noted author on the history, geography and climate of Oregon who died in 2015, became close friends with many of the repeat runners, including Purpura, and the race was a place where they could count on seeing each other every year.

Purpura, who lives in Portland, said the race is a rare opportunity for runners like him to take in an event like the Spray Rodeo.

“It’s an odd mix, but everybody seems to get along fine,” Purpura said, noting that in 1980 he tried for the “daily double” — winning the Eastern Oregon Half, and then entering the rodeo’s wild horse race (an event in which a team attempts to saddle a wild horse and have one member ride one full lap around the ring).

“I’m thankful to be able to be here talking to you,” Purpura said. “I didn’t know what I was getting into — those 2-year-old horses, they don’t want anyone around them or on them. I got bucked off so fast, I was on the ground before the horse’s hooves were on the ground. I didn’t want to get on him that time, but I had to, and I went off just as fast again.”

Rilling said the Eastern Oregon Half was perfectly timed to take advantage of the running and jogging craze of the 1970s. The race hit 100 entrants for the first time in 1975, the year Purpura broke the course record. The all-time participation record of 245 runners was set in 1978, and four-time women’s winner Rhonda Burnett set the women’s course record of 1:22:49 in 1980.

As more and more races have popped up in Oregon, the Eastern Oregon Half has lost some of its notoriety. The race drew at least 100 runners nearly every year between 1980 and 2000, but it has rarely broken the century mark since then (108 raced in the half, 5K and 10K in 2017). Of the top 10 fastest times in race history, the most recent was run by Bend’s Don Stearns in 1993. On the women’s side, the most recent top-10 time was run by Laura Nelson in 1999.

But a few loyal runners keep coming back year after year.

Purpura first entered the race in 1968 as a student at Eastern Oregon College (now University). He had missed most of track season after contracting mononucleosis but felt better by late May, so a friend suggested he get back into competition at the half marathon in Spray. He hitched a ride from La Grande and has rarely missed the race ever since, even though he stopped entering other races about 15 years ago.

“Last year I could have asked for some embalming fluid after I was finished, I was in rough shape,” said Purpura, who plans to compete in the 10K distance at the 2018 race, which will be held this Saturday. “The people there really make the difference. It’s something special for them, while in Portland, they have a race every weekend. But in Spray it’s just once a year, so the people come out and cheer.”

Tim Vandervlugt, who won the race in 1996 and 2000, even took part in 2011 — despite the fact that he was deployed to Iraq at the time. The race director was friends with John Qualls, a Heppner native who was stationed at Joint Base Balad (now Balad Air Base) with Vandervlugt. So they decided to put together a “shadow race,” in which servicemen could run a 13.1-mile race on the base. Eastern Oregon Half organizers sent over race T-shirts and finishers medals, just like the ones handed out back home.

“We ended up getting 16 people,” said Vandervlugt, now 53 and living in La Grande. “Balad is a pretty big base, and we were able to create some loops. It worked out pretty good.”

In 2012, he returned to Oregon and won the race in 1:19:04. His teenage daughter Maia won the 5K last year, and Vandervlugt said he intends to improve on last year’s third-place finish this time around.

The race still does have a certain draw for some runners, even those who are not longtime participants. Charlie Ban, the 2017 winner, had come to Sunriver for a work conference and decided to trek up to Spray at the last minute.

‘I have a lot of nostalgia for that weekend in Oregon, and a lot of it revolves around my trip to Spray,” said Ban, who lives near Washington, D.C., and runs a website focused on local running news. “I don’t think I would have rather done anything else that weekend.”

Ban said he was taken aback by the race course after reading that there is a rise of only 12 feet between the start and the finish. (True, but runners face an immediate 150-foot drop at the start, so the rest of the course is a slow incline to the finish in Spray.) But aside from that, Ban said the rest of the weekend was so much fun that he has spent the past year telling his friends in Oregon and Washington state to check it out for themselves.

“If a race lasts that long, it has to have some substance, and that substance is competent race direction and a strong tradition,” Ban said. “The fact that I got to see the rodeo parade and go to the rodeo afterwards was just outstanding. It really gave me a sense for the community that I couldn’t have gotten any other way, and it felt like I was part of something pretty big for the town of Spray.”

—Reporter: 541-383-0305, vjacobsen@bendbulletin.com