Dr. William House invented device to restore hearing

Published 4:00 am Sunday, December 16, 2012

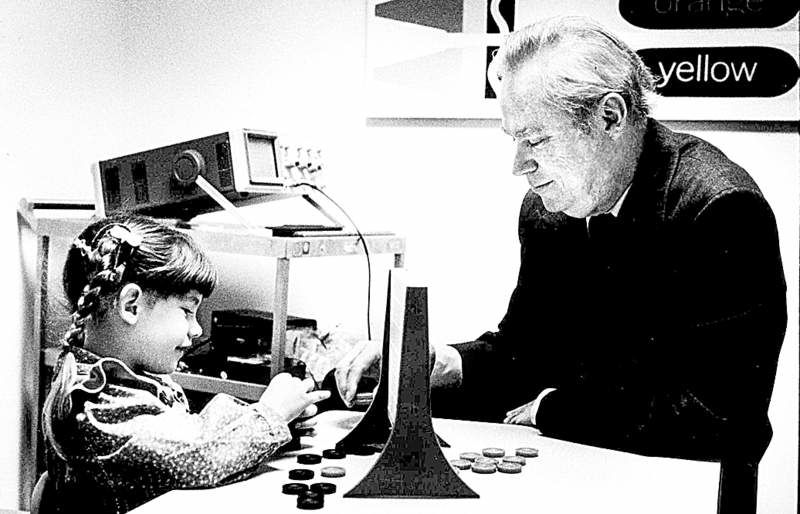

- Dr. William House, seen in 1984, was instrumental in developing the cochlear implant to restore hearing to the deaf.

Dr. William House, a medical researcher who braved skepticism to invent the cochlear implant, an electronic device considered to be the first to restore a human sense, died on Dec. 7 at his home in Aurora, Ore. He was 89.

The cause was metastatic melanoma, his daughter, Karen House, said.

Trending

House pushed against conventional thinking throughout his career. Over the objections of some, he introduced the surgical microscope to ear surgery. Tackling a form of vertigo that doctors had believed was psychosomatic, he developed a surgical procedure that enabled the first American in space to travel to the moon. Peering at the bones of the inner ear, he found enrapturing beauty.

Even after his ear-implant device had largely been supplanted by more sophisticated, and more expensive, devices, House remained convinced of his own version’s utility and advocated that it be used to help the world’s poor.

Today, more than 200,000 people in the world have inner-ear implants, a third of them in the United States. A majority of young deaf children receive them, and most people with the implants learn to understand speech with no visual help.

Hearing aids amplify sound to help the hearing-impaired. But many deaf people cannot hear at all because sound cannot be transmitted to their brains, however much it is amplified. This is because the delicate hair cells that line the cochlea, the liquid-filled spiral cavity of the inner ear, are damaged. When healthy, these hairs — more than 15,000 altogether — translate mechanical vibrations produced by sound into electrical signals and deliver them to the auditory nerve.

House’s cochlear implant electronically translated sound into mechanical vibrations. His initial device, implanted in 1961, was eventually rejected by the body. But after refining its materials, he created a long-lasting version and implanted it in 1969.

More than a decade would pass before the Food and Drug Administration approved the cochlear implant, but when it did, in 1984, Mark Novitch, the agency’s deputy commissioner, said, “For the first time a device can, to a degree, replace an organ of the human senses.”

Trending

One of House’s early implant patients, from an experimental trial, wrote to him in 1981 saying, “I no longer live in a world of soundless movement and voiceless faces.”

But for 27 years, House had faced stern opposition while he was developing the device. Doctors and scientists said it would not work, or not work very well, calling it a cruel hoax on people desperate to hear. Some said he was motivated by the prospect of financial gain. Some criticized him for experimenting on human subjects. Some advocates for the deaf said the device deprived its users of the dignity of their deafness without fully integrating them into the hearing world.

Even when the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology endorsed implants in 1977, it specifically denounced House’s version. It recommended more complicated versions, which were then under development and later became the standard.

But his work is broadly viewed as having sped the development of implants and enlarged understanding of the inner ear. Jack Urban, an aerospace engineer, helped develop the surgical microscope as well as mechanical and electronic aspects of the House implant.

Karl White, founding director of the National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management, said in an interview that it would have taken a decade longer to invent the cochlear implant without House’s contributions. He called him “a giant in the field.”

After embracing the use of the microscope in ear surgery, House developed procedures — radical for their time — for removing tumors from the back portion of the brain without causing facial paralysis; they cut the death rate from the surgery to less than 1 percent from 40 percent.

He also developed the first surgical treatment for Meniere’s disease, which involves debilitating vertigo and had been viewed as a psychosomatic condition. His procedure cured the astronaut Alan Shepard of the disease, clearing him to command the Apollo 14 mission to the moon in 1971. In 1961, Shepard had become the first American launched into space.

In presenting House with an award in 1995, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation said, “He has developed more new concepts in otology than almost any other single person in history.”

House never made any money on the implant. He never sought a patent on any of his inventions, he said, because he did not want to restrict other researchers.