Taking mapping to a new level

Published 4:00 am Monday, March 7, 2011

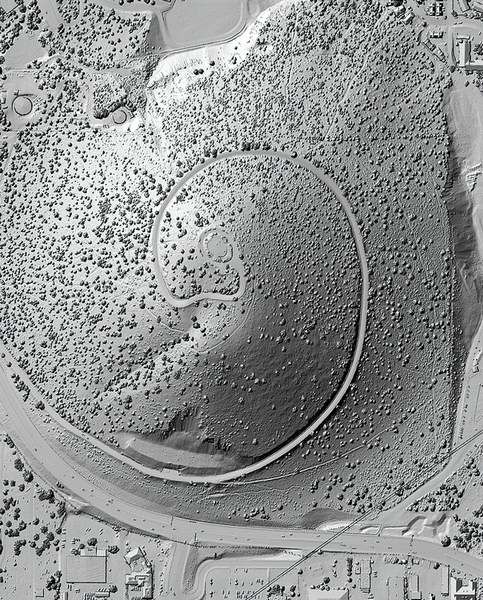

- A lidar image of Pilot Butte in Bend provides precise details of the topography, as well as the vegetation on the butte and nearby cars, houses and even traffic lights.

The image of Pilot Butte, created from about 20 million precise measurements, identifies every tree and shrub on the Bend landmark, the houses nearby and the cars driving along U.S. Highway 20 around the base.

And it’s just one fraction of a map that staff with the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries are piecing together of 2 million acres of the Deschutes Basin. The effort is part of a statewide project to use a relatively new technology called Light Detection and Range — or lidar — to discover more about Oregon’s topography, using the information to plan timber projects, help identify volcanic hazards and more.

“Lidar allows us to make very attractive and informative and just plain cool maps,” said Ian Madin, chief scientist with the state geology department. “So we’re trying to pass some of what we see every day on our computer screens to the general public.”

Last week, the agency released a map that people could buy — either in digital or paper form — that reveals the details of a stretch from Lava Butte to the city of Bend. A CD-ROM of the map is $15, a 3-foot-by-5-foot paper copy is $40, and a laminated version is $60.

Lidar is a technique used to gather many data points, about 100,000 per second, that are used to create maps accurate to within a couple of inches, Madin said. A plane flies over an area, equipped with a laser range finder that sends out pulses of light to the ground below. It measures the distance to the ground, and combines that with the altitude of the plane to come up with a data set of billions of elevation points.

Since 2007, the geology department has been generating these maps and putting them online — completed areas include the Willamette Valley and coastal Oregon. The funds for the project come from other government agencies interested in the data, so the locations of projects depend on what is funded.

“We collect this data where there’s an interest in it, accompanied by money,” Madin said.

About a year ago, the agency started the $1.7-million effort to map the Deschutes Basin, with funding mostly from the U.S. Forest Service, he said, but also from the U.S. Geological Survey, lottery funds through the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Oregon State Parks and a geothermal company.

The results for the entire basin should be available in three to four months, he said, on a Web map viewer on the department’s website. At that point, people can click on an area to see the detailed images of houses, trees, streets, geological faults, streams, river channels and more.

“It provides us with an exceedingly detailed and accurate map,” Madin said.

Many uses

For many people, the lidar maps could just be a pretty picture or a way to explore the features of their neighborhood, Madin said. Or, once the maps are up on the Web viewer, people could print out a section they planned to hike and use it as a regular map.

Or, cities could use the maps to identify all the buildings, street intersections, traffic lights, streams and drainage ditches, he said.

“Everybody needs a good map,” Madin said.

In other areas where the maps are completed, people have used the lidar images to map earthquake faults and landslides, as well as create more accurate maps of floodplains, Madin said. Images also have been used to identify volcano hazards on Mount Hood, and determine where along a river there are enough trees to provide the needed shade for fish.

“We’re just still learning how to extract useful information from it,” Madin said, noting that he is currently working to locate ATV trails in the Ochoco National Forest north of Prineville.

Forest study

Staff with the Deschutes National Forest are kind of leading the way in using lidar technologies for forestry purposes, he said, and trying to gauge the number and size of trees in the forest.

Mike Simpson, an ecologist with the Forest Service, agreed that there are still applications for lidar maps that foresters and others are exploring.

“To some extent, we’re just starting to scratch the surface of what we can use it for,” Simpson said.

So far, with some of the first maps of the Deschutes Basin in the Sisters area, Forest Service staff are using lidar images to identify big trees within the area of its Popper vegetation management project. The agency has to survey for mosses and fungi in areas that have old-growth characteristics, he said, so spotting the big trees on the map helps staff key in on sites that need to be surveyed.

And as part of the new Deschutes Skyline Collaborative project, which will involve projects to reduce the potential wildfire fuels on 100,000 acres to the west of Bend and Sisters, lidar will play a role in helping to calculate how fires would behave before and after the treatments, he said.

“The timing is just perfect,” he said.

Volcano study

The USGS is funding several lidar mapping projects of volcanoes with stimulus money, said Julie Donnelly-Nolan, a geologist with the federal agency’s Volcano Science Center in Menlo Park, Calif. — including sections of Newberry Volcano.

There, one of the ideas is to use the precise elevation changes visible on lidar maps to model the effects of something like the eruption of a little cinder cone, she said. Past lava flows from eruptions in Newberry have reached the area that’s now Bend, she said, so scientists want to know where lava might head if there were a future eruption.

Donnelly-Nolan also is trying to determine the story of Newberry Caldera — what erupted when, and where the flows went — so studying the different topographical features on the lidar maps could help her study large areas without walking it all, she said.

Watershed study

The statewide lidar program also received $500,000 in lottery funds for the 2009-11 biennium, as well as funds in the previous biennium, said Ashley Seim, GIS and website specialist with the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board. The information allows people to see precisely where streambeds or watersheds are, she said, plan future paths for streams as part of restoration projects, and even study the vegetation growing along waterways.

The Upper Deschutes Watershed Council has used lidar images in Sisters, said Ryan Houston, the organization’s executive director. Whychus Creek runs through town, and the lidar images help show where the creek’s floodplain overlaps with houses, and where potential restoration work could help prevent possible property damage.

“We used it as a way to talk about that issue, and plan how we work upstream and downstream of the city, so we can make it better,” Houston said.

On the Web

The Web viewer for the completed images, which includes sections of the Willamette Valley and Oregon Coast and will include parts of the Three Sisters and Deschutes Basin area by this summer, is at www.oregon geology.org/sub/lidardata viewer/index.htm.

For more information about the state’s lidar project, visit www.oregongeology.org/sub/projects/olc/default.htm.