Thornberry’s story

Published 5:00 am Saturday, March 19, 2011

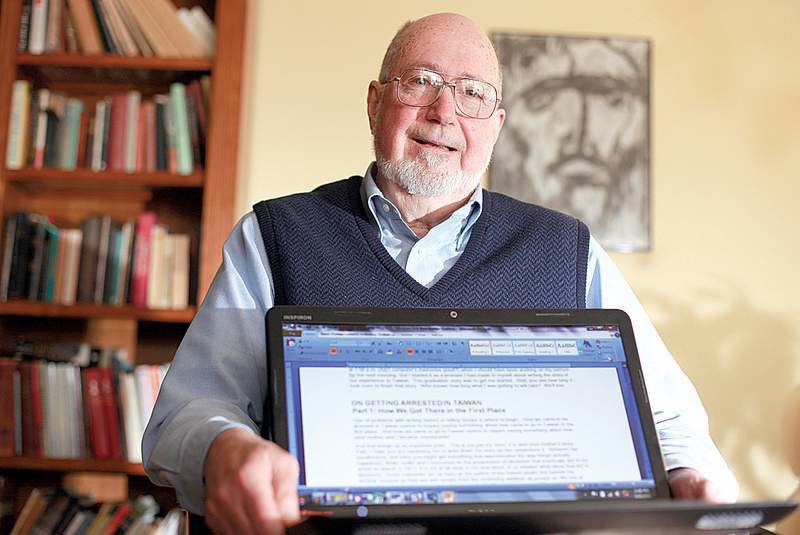

- Milo Thornberry holds his laptop computer showing the first of 16 letters he sent to his children in August 2002 which became the basis for his recently released book “Fireproof Moth: A Missionary in Taiwan's White Terror.” His daughter had encouraged him to write about his experiences in Taiwan which led to the arrest of himself and his wife on March 2 1971. The book chronicles Thornberry's role in helping human rights advocate and future presidential candidate Peng Ming-min escape from Taiwan in 1970.

Milo Thornberry never intended to tell anyone outside his close circle about his life in Taiwan, let alone share it in a book.

The 73-year-old Bend resident, a retired Methodist pastor, said he told only a few people about his past, which is worthy of a spy thriller: smuggling cash to families of political prisoners, slipping victim names to Amnesty International, and orchestrating the escape of an internationally known scholar and democracy activist.

Thornberry feared for friends who remained. They could be arrested for having associated with him, he said, or worse.

But change has come to the island where he risked so much as a missionary in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Not only is Thornberry now free to tell his tale, he said he feels it’s an obligation.

“I’d like for Americans to know a little bit more about this history,” he said. “My role is only a couple of sentences in this struggle in Taiwan.”

Last month, publisher Sunbury Press released “Fireproof Moth: A Missionary in Taiwan’s White Terror.” The nonfiction work chronicles Thornberry’s journey to becoming a missionary in Taiwan for five years with his then-wife, Judith Thomas. It describes his growing awareness of the oppressive political regime there and how his activities led to his arrest and expulsion from the country in 1971, an event that made the front page of The Washington Post.

And it reveals how he helped secret democracy activist Peng Ming-min out of Taiwan. Peng’s disappearance was of such political importance at that time that recently declassified federal documents show that Henry Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, and Chinese Premier Chou En-lai discussed it when the two met in Beijing in 1971.

Taiwanese politics

The Taiwan Thornberry writes of in “Fireproof Moth” is not the democratic one that exists today.

Taiwan reverted to Chinese rule at the close of World War II. When Communists took over China in 1949, roughly 2 million people fled to the island of Taiwan, according to the U.S. State Department website. Nationalist Party leader Chiang Kai-shek established a “provisional” Republic of China capital in Taipei. And politicians in both Beijing and Taipei maintained that they were the real leaders of China.

The Nationalist Party regime in Taipei, as the non-Communist government, was aligned with the world’s democracies. Yet it imposed martial law on Taiwanese citizens in 1947 — and maintained it for 40 years.

Taiwanese journalist James Wang, who has lived in Washington, D.C., since 1978 and written several books on Taiwanese politics, said those who voiced opposing political opinions were arrested. Sometimes they just disappeared. There were no elections and no freedom of assembly, speech or press.

The Nationalist Party claimed it maintained martial law because the Communists could overrun the island at any time, Wang said. Party leaders promised they would end the state of emergency once they again assumed control on the mainland.

Thornberry and his wife arrived in this environment in 1967. Moving in academic circles, they soon befriended Peng, a professor who had served a 15-month prison sentence for writing a pamphlet that called for a new constitution and an independent Taiwan.

Thornberry said the ignorance he and his wife had enjoyed soon disappeared. They learned that the families of political prisoners suffered, as they were pushed out of jobs and housing. In accordance with their faith, he said, they began trying to help.

Coordinating with Peng and others, Thornberry arranged for journalists and other visitors to meet with citizens unsatisfied with the Taiwanese government. They raised money for the families of political prisoners.

The most daring act, Thornberry said, was helping Peng escape.

Peng, educated in Paris and Montreal and at one time a student of Kissinger’s in a Harvard symposium, became known on the international stage as a scholar of international law. After his release from prison, he was placed under house arrest, although he regularly snuck out in the middle of the night. “Fireproof Moth” tells of how by 1970 Peng believed the Nationalist Party’s tolerance of him was wearing thin.

Thornberry said he planned Peng’s escape, using an altered Japanese passport and an elaborate disguise to allow him to board an airplane out of the country. Peng flew to Japan, and then shortly after that to Sweden. En route, he tore up the fake passport and sought amnesty when he arrived in Stockholm.

About a year later, Peng was teaching at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor despite the Taiwanese government’s pleas that he be denied entry to the U.S., according to the same March 1971 story in The Washington Post that detailed the arrest of the Thornberrys.

The Thornberrys were placed under house arrest in March 1971. The charge, armed soldiers told them, was activities unfriendly to the state. Coincidentally, Thornberry said, The Washington Post reporter was due to call them that day. When he did, Thornberry’s then-wife was able to tell him of their arrest before soldiers yanked the phone away.

They were expelled from the country days later.

Thornberry believes the government didn’t know of his role in Peng’s escape. The couple’s activities and connections, he said, had caught up with them.

Writing his story

Martial law in Taiwan was not lifted until 1987. The island then took its first steps toward political liberalization.

In 1996, Taiwan residents for the first time voted for a president. Peng was one of the four presidential candidates.He did not win.

Thornberry returned to Taiwan for the first time in 2003, when he and others were honored in a ceremony for their contributions to Taiwan.

“That meant a lot to me,” Thornberry said, his voice cracking with emotion.

But it wasn’t until 2008 that Thornberry decided to write “Fireproof Moth.”

That year he again returned to Taiwan to participate in a panel. It was then that he met Wang, also there for the panel, who in his own work in Washington, D.C., had come across Thornberry’s name in recently declassified documents in the National Archives. He gave Thornberry a copy.

“Milo is really a low-key person,” Wang said. “When we spoke, he didn’t reveal how he helped Peng escape from Taiwan. When I found out, I said, ‘You have to write about this.’ ”

Wang also volunteered to help. He returned to the National Archives and found an entire folder on the Thornberrys.

While discussion of Thornberry came up in documents, Wang said it didn’t appear that the Taiwanese or Americans had connected him with Peng’s escape.

Thornberry said friends in Taiwan also helped him with research there. Peng, still a good friend who since his flight has lived part-time in the U.S., assisted as well.

Right now “Fireproof Moth” is available only in English. But Thornberry said he is in talks with a publisher in Taiwan, who is interested in releasing it there in Chinese.

Wang hopes the account does come to Taiwan.

“They would rather not have it published in Chinese in Taiwan,” he said of the Nationalist Party, which won the presidency again in 2008. “They don’t want the younger generation to read it.”

“But it’s an important page in Taiwan’s political history,” Wang continued. “We should know this and we should appreciate Milo’s help.”

“Fireproof Moth: A Missionary in Taiwan’s White Terror” by Milo L. Thornberry is available in paperback for $14.95. It’s also available for both the Kindle and Nook for $4.99. Copies are available by order through Amazon or Barnes and Noble, or locally at Between The Covers bookstore in Bend.