Honoring slave who helped create Jack Daniel’s

Published 10:04 pm Tuesday, August 15, 2017

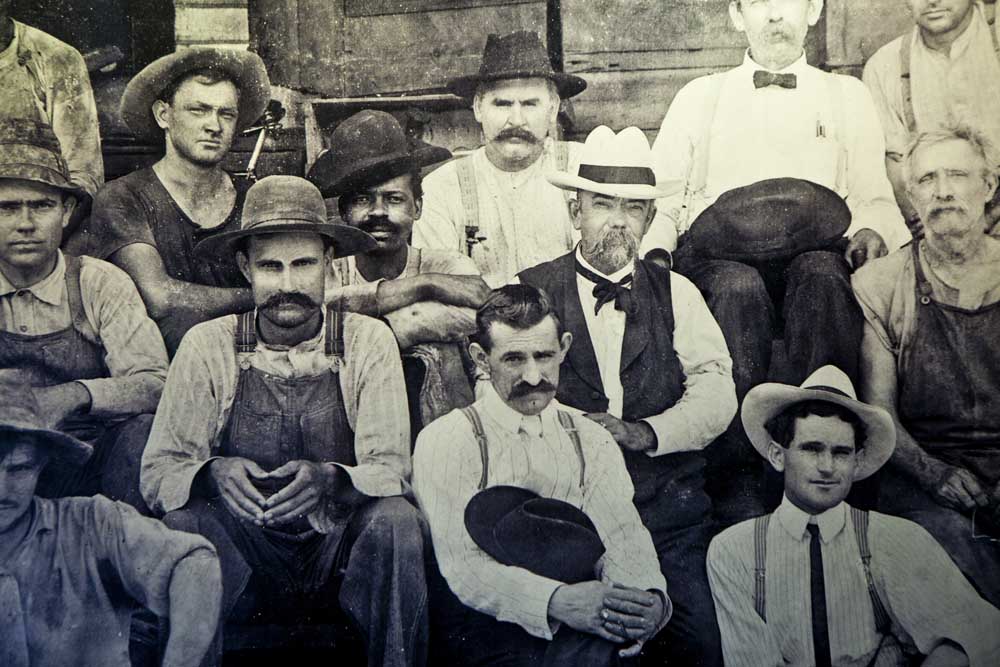

- An undated photo from Jack Daniel’s old office of Daniel, center in white hat, and an unidentified black man who may be the slave Nearest Green or one of his sons. (Handout via The New York Times)

LYNCHBURG, Tenn. — Fawn Weaver was on vacation in Singapore last summer when she first read about Nearest Green, the Tennessee slave who taught Jack Daniel how to make whiskey.

Green’s existence had long been an open secret, but in 2016 Brown-Forman, the company that owns the Jack Daniel Distillery here, made international headlines with its decision to finally embrace Green’s legacy and significantly change its tours to emphasize his role.

“It was jarring that arguably one of the most well-known brands in the world was created, in part, by a slave,” said Weaver, 40, an African-American real estate investor and author.

Determined to see the changes herself, she was soon on a plane from her home in Los Angeles to Nashville. But when she got to Lynchburg, she found no trace of Green. “I went on three tours of the distillery, and nothing, not a mention of him,” she said.

Rather than leave, Weaver dug in, determined to uncover more about Green and persuade Brown-Forman to follow through on its promise to recognize his role in creating America’s most famous whiskey. She rented a house in downtown Lynchburg and began contacting Green’s descendants, dozens of whom still live in the area.

Scouring archives in Tennessee, Georgia and Washington, D.C., she created a timeline of Green’s relationship with Daniel, showing how Green had not only taught the whiskey baron how to distill, but had also gone to work for him after the Civil War, becoming what Weaver believes is the first black master distiller in America. By her count, she has collected 10,000 documents and artifacts related to Daniel and Green, much of which she has agreed to donate to the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

Through that research, she also located the farm where the two men began distilling — and bought it, along with a 4-acre parcel in the center of town that she intends to turn into a memorial park. She even discovered that Green’s real name was Nathan; Nearest (not Nearis, as has often been reported) was a nickname.

She is writing a book about Green, and last month introduced Uncle Nearest 1856, a whiskey produced on contract by another Tennessee distillery; she says she will apply the bulk of any profits toward her expanding list of Green-related projects.

Weaver’s biggest success, however, came in May, when Brown-Forman officially recognized Green as its first master distiller, nearly a year after the company vowed to start sharing Green’s legacy.

“It’s absolutely critical that the story of Nearest gets added to the Jack Daniel story,” Mark McCallum, the president of Jack Daniel’s Brands at Brown-Forman, said in an interview.

The company’s decision to recognize its debt to a slave, first reported last year by The New York Times, is a momentous turn in the history of Southern foodways. Even as black innovators in Southern cooking and agriculture are beginning to get their due, the tale of American whiskey is still told as a whites-only affair, about Scots-Irish settlers who brought Old World distilling knowledge to the frontier states of Tennessee and Kentucky.

The company had intended to recognize Green’s role as master distiller last year as part of its 150th anniversary celebration, McCallum said, but decided to put off any changes amid the racially charged run-up to the 2016 election. “I thought we would be accused of making a big deal about it for commercial gain,” he said.

It didn’t help that many people misunderstood the history, assuming that Daniel had owned Green and stolen his recipe. In fact, Daniel never owned slaves and spoke openly about Green’s role as his mentor.

And so the company’s plans went back on the shelf, and might have stayed there had Fawn Weaver not come along.

“It’s something my grandmother always told us,” said Debbie Ann Eady-Staples, a descendant of Green who lives in Lynchburg and has worked for the distillery for nearly 40 years. “We knew it in our family, even if it didn’t come from the company.”

Nothing stays quiet in Lynchburg (population 6,319) for long, especially when it involves the biggest employer in town, and by late March Weaver was meeting with McCallum, the brand president, in the makeshift office she had set up in a rundown house on her newly acquired farm.

With a sampling of her estimated 10,000 documents and artifacts spread across a table between them, it quickly became obvious that Weaver, who had no previous background in whiskey history, knew more about the origins of Jack Daniel’s than the company itself. What was supposed to be a preliminary meeting turned into a six-hour conversation.

McCallum says he left reinvigorated, and within a few weeks he had plans in place to put Green at the center of the Jack Daniel’s storyline. In a May meeting with 100 distillery employees, including several of Green’s descendants, he outlined how the company would incorporate Green into the official history, and that month the company began training its two dozen tour guides.

Eady-Staples, who met privately with McCallum before the big meeting, said she was proud that her employer was finally doing the right thing. “I don’t blame Brown-Forman for not acting earlier, because they didn’t know,” she said. “Once they did, they jumped on it.”

And although there is no known photograph of Green, the company placed a photo of Daniel seated next to an unidentified black man — he may be Green or one of his sons who also worked for the distillery — on its wall of master distillers, a sort of corporate hall of fame.

“We want to get across that Nearest Green was a mentor to Jack,” said Steve May, who runs the distillery’s visitors center. “We have five different tour scripts, and each one incorporates Nearest. I worked some long days to get those ready.”

May said that so far, visitor response to the new tours spotlighting Green’s contribution has been positive. It’s not hard to see why: At a rough time for race relations in the United States, the relationship between Daniel and Green allows Brown-Forman to tell a positive story, while also pioneering an overdue conversation about the unacknowledged role that black people played in the evolution of American whiskey.