St. Charles prices highest in state for some procedures

Published 8:25 am Monday, August 14, 2017

- St. Charles prices highest in state for some procedures

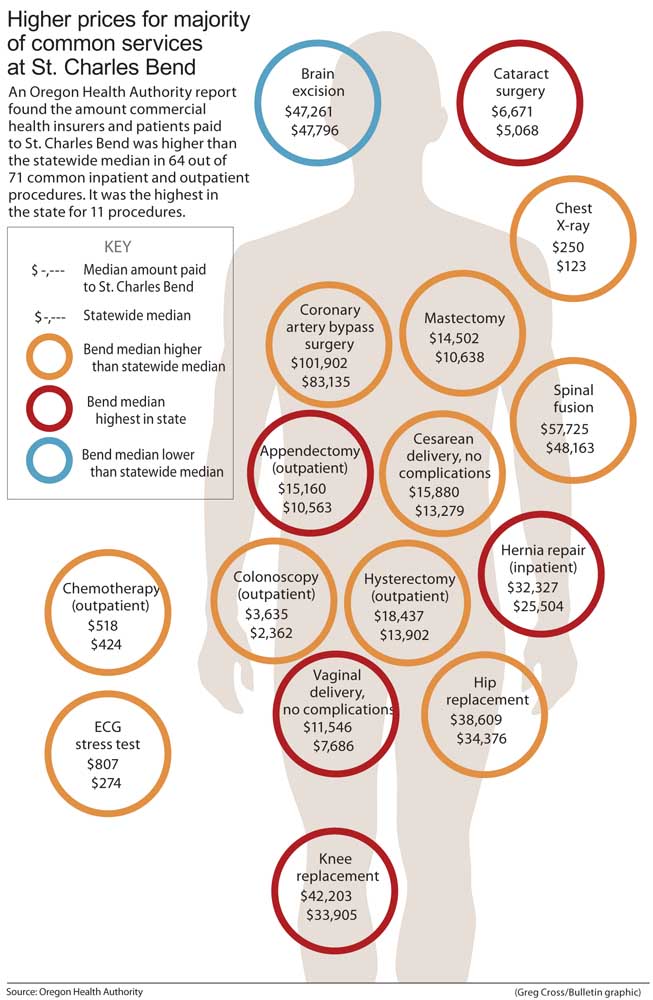

Insurers and patients paid St. Charles Bend more than the statewide median for 90 percent of the common procedures ranked in a new Oregon Health Authority report.

Of 71 services, payments to St. Charles Bend were above the statewide median for 64 and highest in the state for 11, including knee replacements, outpatient appendectomies and vaginal deliveries without complications. The numbers come from the second annual Hospital Payment Report, which is mandated by a 2015 law requiring the OHA to publicize payments from health insurers to hospitals for common inpatient and outpatient procedures.

The data is from 2014 and 2015. It provides a window into what hospitals charge private insurers for services, information that wasn’t publicly available before the 2015 law. The payments represent what private insurers paid for the procedures in addition to patient contributions in the form of co-payments, deductibles or co-insurance.

The report lays bare striking disparities in payment amounts across hospitals. For example, insurers paid Salem Hospital a median of $5,303 for an outpatient appendectomy, the surgical procedure to remove the appendix. They paid St. Charles Bend a median of $15,160 for the same procedure.

Compared with last year’s report, this one shows even wider variations between payments hospitals received for the same services, said Steven Ranzoni, a health policy advisor in the Oregon Health Authority’s Health Policy and Analytics Division.

“Prices aren’t getting tighter,” he said. “They’re not getting closer. They’re actually showing greater variance than they’ve shown before.”

The report lists median payments, the point at which half the payments are below and half are above, rather than averages because a handful of very high bills tend to skew averages.

Reasons for differences

Variations in payments can be due to a hospital’s location, its patient volume, its patients’ insurance status and a number of other factors, Ranzoni said. Research has shown hospitals that are the sole providers in a region, such as St. Charles Health System in Central Oregon, tend to price services between 15 and 20 percent higher than those outside of that region, he said.

Jenn Welander, St. Charles’ chief financial officer, explained the health system’s prices are built on the cost of providing services and the reimbursement it receives from private and public insurers. The government programs Medicaid and Medicare make up 75 percent of the health system’s business, but they pay below the cost of providing services, she said.

St. Charles also provides a wide array of services, including cardiac and cancer care, but at lower volumes than larger health systems.

“Because of that breadth that we offer, it can make things more expensive because we don’t have economies of scale around the volume,” Welander said.

St. Charles has raised prices in recent years in part because it tends to pay more than larger health systems for pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and implants. It doesn’t have as much negotiating power as multistate systems like Kaiser Permanente, Welander said. It also pays more to have those products delivered.

In 2009, St. Charles raised its prices across the board by 13 percent, Welander said. In 2010, it did so by 10 percent. Today, neither patients nor insurers will tolerate the same level of increases, she said. In 2016 and 2017, she said St. Charles bumped up prices by about 4 percent.

St. Charles Redmond was included on several measures; payments to the hospital ranged above and below those made to the Bend hospital. To be included on a measure, a hospital must have performed that procedure at least 10 times.

Median payments for an uncomplicated vaginal delivery were $1,074 less in Redmond than in Bend and an outpatient hernia repair was about $1,200 less in Redmond. By contrast, the median payment for a hysteroscopy, a procedure to look into the uterus, was $2,522 more in Redmond than in Bend.

Old, but still useful

The data in the OHA’s report comes from the state’s All Payer All Claims database, a repository of all health insurance claims from commercial insurers, Medicare and Medicaid. At any one time, the database contains data for approximately 3.2 million Oregonians.

The database operates on a roughly 18-month time lag because the claims must be finalized before they’re submitted, Ranzoni said. That makes the information less useful as a barometer of current prices, he said.

Still, as of 2016, five other states used their own all payer claims databases for similar public reporting purposes, said Suzanne Delbanco, executive director of the Catalyst for Payment Reform, a nonprofit focused on helping large employers and other consumers save money on health care.

The data in the OHA’s new report won’t show people how much they’ll pay, but it will show how hospital prices compare, she said.

“Yeah, it’s out of date, but it helps educate people on the ballpark of what things cost and the relative prices across providers,” Delbanco said.

The Catalyst for Payment Reform gave Oregon a B on its latest report card on price transparency laws — up from an F in 2015 — because of last year’s Hospital Payment Report.

When the law that mandates the OHA report was debated, critics argued the All Payer All Claims data would be too old to be helpful. Consumer advocates championed a different bill that would have required hospitals to post their prices both on their websites and in their facilities. It also would have required that they give cost estimates upon request.

St. Charles’ billing office provides price estimates, including working with patients’ insurers to determine their out-of-pocket costs, for scheduled procedures, Welander said. For nonscheduled procedures, Welander said, the health system likely wouldn’t be able to work with insurers to provide the same level of specificity.

Ranzoni said patients won’t be able to use the OHA’s report to determine how much they’ll pay for procedures. To get that information, he encourages them to call their insurers and ask which hospitals are within their networks and, of those, which offer the cheapest price.

“Make them do the work for you,” he said. “That’s where you can have an ability to be a participant in the system.”

Website forthcoming

It’s important to remember that a hospital’s price alone doesn’t represent the total cost of a procedure, said Rick Gundling, senior vice president for health care financial practices with the Healthcare Financial Management Association. Hospital prices typically don’t include what surgeons or anesthesiologists charge, he said. They also don’t include outpatient visits before and after the procedure.

The law mandating the hospital payment reports requires they be posted on a website in a “consumer friendly format” that’s “easily accessible by consumers.” The most recent report, however, is broken into a handful of large documents on the OHA’s website.

In the future, Ranzoni said the OHA plans to put the data into an interactive website where users can search by procedure to get a chart with the payments by hospital.

But it doesn’t appear that will happen soon.

“I don’t even want to pretend to guess at that,” Ranzoni said when asked when that website might launch.

The Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems maintains the website oregonhospitalguide.org. It features payment data from last year’s OHA Hospital Payment Report, but not from the report released this month.

— Reporter: 541-383-0304, tbannow@bendbulletin.com

Editor’s note: The chart “Higher prices for majority of common services at St. Charles Bend,” which accompanies this story has been corrected. In the original version, the type of surgery for appendectomy was incorrect.

The Bulletin regrets the error.

To view the report, visit bit.ly/bbhospitalprices and open the links under “Hospital Payment Reports.”