Pill splitting

Published 4:00 am Thursday, March 10, 2011

- Pill splitting

For years patients have taken advantage of a quirk in the pricing system for prescription drugs, splitting higher dose tablets in half to save money. But a recent study from researchers in Belgium suggests it’s not always a safe practice.

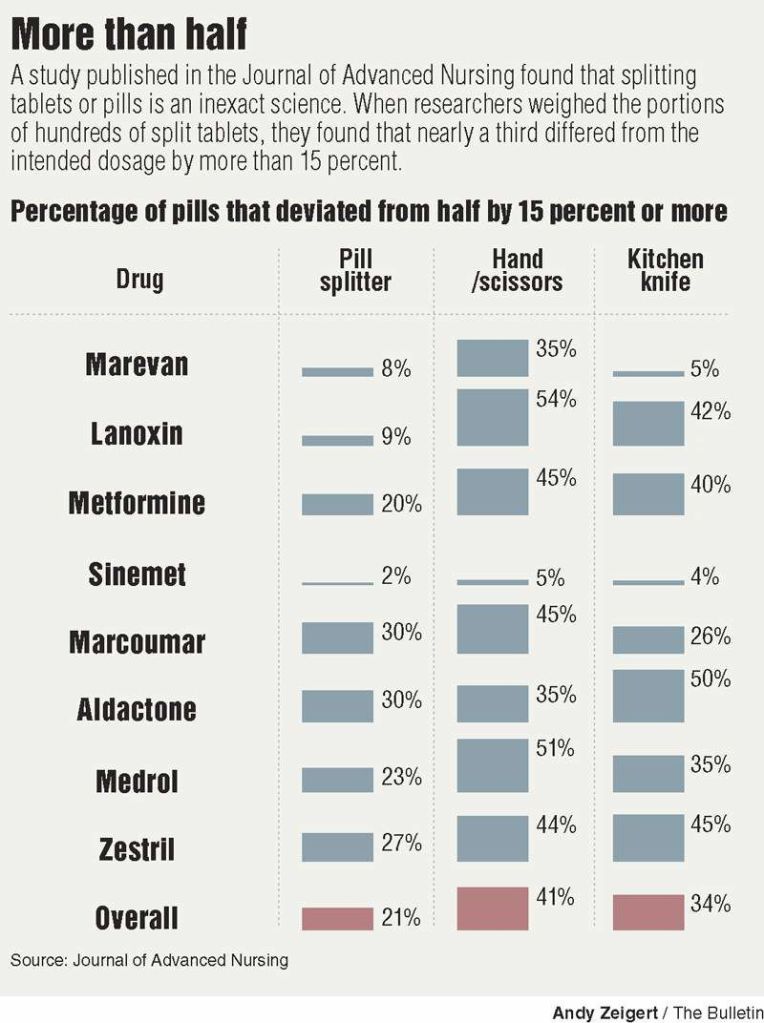

In a study published earlier this year in the Journal of Advanced Nursing, researchers recruited five test subjects to split 10 different types of prescription drugs into halves or quarters. Nearly a third of fragments deviated from their expected weight by more than 15 percent.

“Tablet splitting is widespread in all health care sectors. It’s done for a number of reasons: to increase dose flexibility, to make tablets easier to swallow and to save money for patients and health care providers,” said Dr. Charlotte Verrue, the lead author of the study. “However, the split tablets are often unequal sizes and a substantial amount of the tablet can be lost during splitting.”

Because some drugs have a very narrow margin between effective and dangerous doses, tablet splitting could have serious consequences for the patients, the authors said.

“Not all formulations are suitable for splitting and, even when they are, large dose deviations or weight losses can occur,” Verrue said. “This could have serious clinical consequences for drugs where there is a small difference between therapeutic and toxic doses.”

Tablet splitting has become a popular way of saving money because pharmaceutical companies price their medications primarily based on the number of pills, not the dosage. A patient paying out of pocket for a 10 mg pill that costs $300 for a month’s supply could purchase the same number of 20 mg pills and split them, reducing the monthly cost to $150. Patients with insurance coverage, meanwhile, could get a two-month supply for a single co-pay.

Some pills — including capsules or extended release formulations — cannot be split. But many others are manufactured as scored tablets that facilitate splitting.

The researchers tested three ways of splitting pills — using a pill-splitting device, a kitchen knife or splitting scored pills by hand and unscored pills with scissors. The splitting device was the most accurate, producing a 15 to 25 percent deviation 13 percent of the time, and more than 25 percent 8 percent of the time. Using a kitchen knife produced the most variation and was more likely to produce fragments that crumbled.

“Based on our results, we recommend use of a splitting device when splitting cannot be avoided, for example when the prescribed dose is not commercially available or where there is no alternative formulation, such as a liquid,” Verrue said.

For some drugs, even variations of 15 to 25 percent may not have any negative results, especially if the patients take the two halves of a single pill on consecutive days. If patients split all their pills for the month at one time and comingle the fragments, doses can vary significantly.

The researchers chose drugs that were commonly split either for economic or therapeutic reasons. Four of the tablets were reported by nurses to be particularly difficult to split consistently.

One of the pills in the test was a generic form of warfarin, which requires substantial testing and monitoring to find the most effective dose. Yet the study found that even with a pill splitter, some fragments were off the target dose by as much as 50 percent.

The Food and Drug Administration and the American Medical Association recommend against tablet splitting unless it’s specified in the drug’s labeling information. And pharmacy groups, including the American Pharmacists Association, have opposed mandatory pill splitting policies. Some insurers require pill splitting in certain cases, while others provide a break on copay for patients who will split tablets.

Patients should ask their doctors or pharmacists whether pills can be safely split. Physicians must prescribe the higher dose for patients who intend to split. Some critics of pill splitting warn the practice can lead to confusion in patient records, which may record the dose prescribed but not the intention to split drugs. Critics also warn that splitting pills is more likely to lead to medication errors if a patient forgets whether the pills in question need to be split or not.