All About Beaujolais

Published 11:56 pm Thursday, September 21, 2017

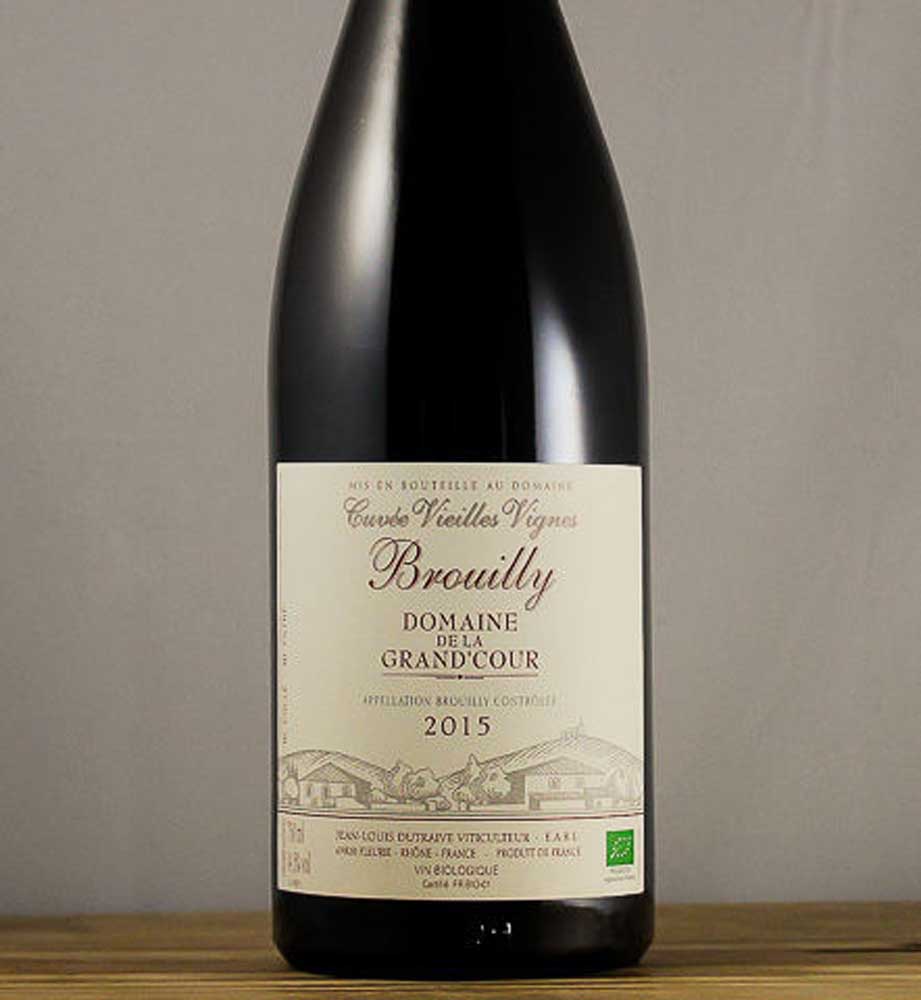

- The 2015 Brouilly ($35), a Vieilles Vignes selection from Domaine de la Grand’Cour, is at once darthy but light, with flavors of blueberry, raspberry, cherry and currant shining through. It offers a suggestion of mushroom on the palate and a silky finish. (Submitted photo)

France’s Beaujolais region, stretching along the west bank of the Saône River south of Burgundy, is smaller by far than the Willamette Valley.

Yet for centuries, it has been producing wines regarded as some of the world’s most popular.

“Its flavor is subtle and light, which makes it a good introductory wine for young drinkers,” Inter Beaujolais export manager Charles Rambaud explained to me during a visit to Portland last week.

That statement struck a personal note for me. In my early 20s, as my tastes evolved from college-era jug wines to slightly more sophisticated varietals, I discovered Beaujolais-Villages. This fruit-forward, dry-on-the-finish wine became my “go-to” choice when I wanted to impress a date. In particular, I liked bottles from winemaker Louis Jadot.

Jadot is still making good wines, Rambaud assured me, but Jadot is not alone. In fact, there are about 2,000 winemakers in the small province of Beaujolais, 30 miles north-to-south and less than half that wide. With only 25,000 acres of land planted in grapes, to say the average estate is small would be an understatement.

Yet there is great variety in the region’s distinctive terroirs. Soil that ranges from limestone to schist and granite, and notable variations in heat and precipitation, have created a dozen different appellation zones.

Ten of them are designated as “Cru” wines (from north to south, these are Saint-Amour, Juliénas, Chénas, Moulin-à-Vent, Fleurie, Chiroubles, Morgon, Régnié, Brouilly and Côte de Brouilly). More basic Beaujolais and mid-level Beaujolais-Villages wines are grown in vineyards that flank and surround the “Cru” areas.

Cru varietals

At the annual Feast Portland food and wine festival, assisted by the Park Avenue Fine Wines shop in downtown Portland, Rambaud offered pours of a dozen different Beaujolais wines — none priced above $35, some as little as $12.

My favorite came from Brouilly, southernmost of the Cru regions. The 2015 Domaine de la Grand’Cour, Vieilles Vignes ($35), was at once earthy but light, with a suggestion of mushroom on the palate and a silky finish. Flavors of raspberry, blueberry, cherry and currant shone through. Rambaud privately confessed that this was also his favorite of the selection.

Although the Côte de Brouilly is entirely embraced within Brouilly, its wines (from the slopes of an ancient volcano) are known to be more medium-bodied, and should age at least a year. I found the 2015 Nicole Chenrion ($24) to be less earthy and more deeply concentrated than the Grand’Cour.

The Fleurie region, whose Crus are among the most widely exported to the United States, are also medium bodied. I tasted the 2015 Domaine de la Chapelles des Bois, Grand Pré ($18) and the 2015 Anne-Sophie Dubois, L’Alchemiste ($32). The Grand Pré had a floral bouquet and a dry finish. The L’Alchemiste had a velvet texture, but would benefit from more time in the bottle.

The Cru Beaujolais grown in the northern part of the region, nearest to Burgundy, is more full-bodied and is recommended for at least four years of aging. The two varietals I sampled were notably more tannic, and thus astringent, than other Beaujolais wines. A Chénas from Pascal Granger (Aux Pierres, 2014, $17), had an aroma of roses and oak; it required extra time uncorked to allow it to breathe before drinking. A Moulin-à-Vent from Georges Duboeuf (Domaine de Rosiers, 2015, $20) was highly structured but too young yet to be fully enjoyed.

Making the wine

Georges Duboeuf is the region’s largest producer and exporter; its wines are widely available in the Northwest. Many of these are the more commonplace Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages varietals, typically priced several dollars less than Cru.

Duboeuf’s 2015 Beaujolais-Villages ($14), and a 2015 Henry Fessy Beaujolais-Villages ($12), were both uncomplicated sipping wines. Designed to be enjoyed within two years of their release, typically in March following an autumn harvest, they were pleasant wines, fruit-forward with dry finishes.

Basic Beaujolais is the classic, inexpensive and easy-drinking wine of bistros in Paris.

Some Beaujolais producers also make small amounts of white wines (labeled Beaujolais Blanc or Mâcon-Villages) and rosé wines. A 2016 Beaujolais Rosé from Domaine Dupeuble ($16) was a lovely summer wine that I might gladly have sipped with Brie and crackers on a warm, non-smoky day.

Rambaud told me Beaujolais wines are made by very traditional methods that incorporate carbonic maceration and malolactic fermentation. Hand-picked, whole-cluster grapes are thrown into tanks so large, the grapes on the bottom are crushed by the weight of gravity. Thus, fermentation begins in a low-oxygen environment, with the natural yeasts and acidity in the grape skins inducing a fruity flavor.

The longer the grapes ferment, the more tannins develop along with a fuller-bodied wine. “It all comes down to the winemaker,” Rambaud noted. The subsequent conversion of malic to lactic acid, with the inoculation of desirable bacteria, helps to integrate fruit and oak, and softens the wine when it is barreled.

As whole-cluster grapes cannot macerate as long as those removed from the stem, an increasing number of winemakers are employing modern Burgundian techniques and creating batches from destemmed grapes, Rambaud said. Higher-quality Cru varietals may be blends of whole-cluster and individual grapes, he said.

— John Gottberg Anderson can be reached at janderson@bendbulletin.com.