Short-term enrollment tripled since insurance mandate

Published 3:47 pm Wednesday, March 15, 2017

- Short-term enrollment tripled since insurance mandate

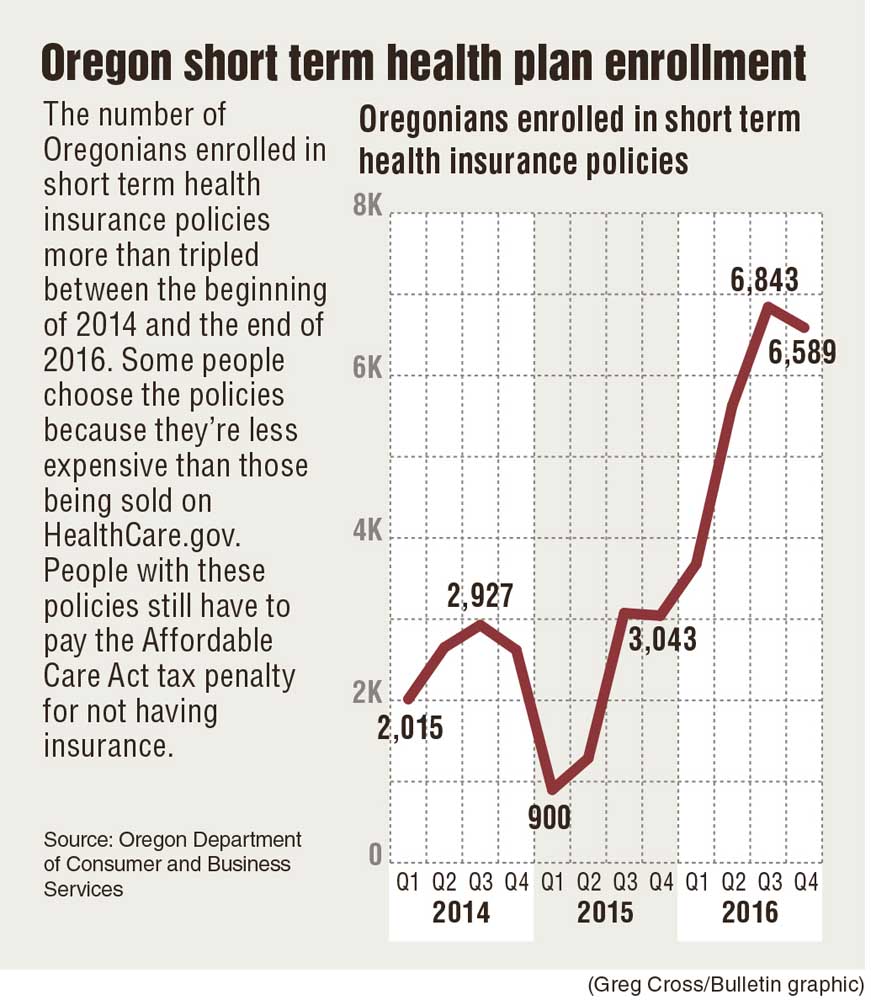

The number of Oregonians enrolled in cheaper, short-term health insurance policies has more than tripled since the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate took effect at the beginning of 2014.

Roughly 2,000 people had the policies, which under Oregon law can last up to 12 months, at the beginning of 2014, compared with about 6,600 at the end of 2016. Since short-term policies aren’t subject to ACA rules that require coverage for things like preventive care and maternity care, those who have them still have had to pay tax penalties for not having insurance.

Even with the penalty, though, some people have found they still save money. Some of the policies are available in Bend for less than $30 per month on AgileHealthInsurance.com, a website that sells short-term health insurance.

The monthly premiums on ACA policies have steadily increased since 2014, largely the result of sick people getting coverage who weren’t previously able to. The policies also are required to cover services like preventive screenings, maternity care, prescription drugs, mental health, emergency care and pediatrics.

When it comes to short-term plans, “You can get a plan that’s just basic, catastrophic coverage without a lot of those benefits included,” said Sam Gibbs, the executive director of AgileHealthInsurance.com.

Since Agile’s launch in May 2015, the company has seen at least 75 percent sales increases year over year, Gibbs said.

“We’re seeing fairly dramatic growth as people are looking for affordable health insurance,” he said.

A new federal law that took effect Jan. 1 throws a major wrench into the short-term market. Now, the policies can only last up to 3 months. To soften the blow, the government is letting policies sold before April 1 last until Dec. 31, 2017. A measure that’s currently before the Oregon Legislature would tweak state law to align with the new federal law.

There are major caveats to short-term policies. The biggest one is that they can reject coverage for pre-existing conditions, a practice that’s banned under the Affordable Care Act. The insurers are sneaky about that, too: They’ll still sell the policy, but won’t cover services related to a condition they deem pre-existing, said Don Klippenes, president of Health Insurance Strategies in Bend. People may have forgotten about an abnormal pap smear or high prostate reading.

“Now, all of a sudden, I don’t have coverage for any of those things related to that,” he said. “You’re thinking that’s what you’re buying coverage for.”

Unlike ACA policies, which can only be purchased during a specific time period — usually November to January — people can buy short-term policies any time. They’re designed for people facing gaps in coverage, such as leaving a job and starting a new one in a few months. Gibbs provided the example of his daughter, who graduated from college and started a new job three months later. There’s also retirees who are close to qualifying for Medicare, he said.

Nowadays, though, Gibbs is benefiting from the confusion surrounding whether the ACA will even exist next year.

“Since November, people have gone to short-term policies to kind of hold them over to whatever the next replacement for the ACA is,” he said.

Gayle Woods, a senior policy adviser for the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services, which regulates insurance, said she believes the new federal rules on short-term policies were prompted by concerns that people were buying them to circumvent ACA requirements and thus harming themselves by not having adequate coverage.

“For people with health issues, that might not be the best thing for them,” she said. “They would be paying money for a policy they wouldn’t get full value of.”

Some have raised the concern that people might use short-term policies while they’re healthy and then enroll in ACA policies once they get sick, thus destabilizing the ACA market.

For his part, Gibbs said he doesn’t think there are enough people enrolled in short-term policies to have an effect. But on an individual basis, he “absolutely” encourages people to do that.

The new federal law also doesn’t allow people to simply renew short-term policies after three months, although they can re-apply and re-enroll in the policy after three months.

It also requires the policy materials to contain a written disclaimer telling people they’ll still be subject to a tax penalty. Last week, some media outlets reported that the Internal Revenue Service will no longer enforce the tax penalties for not having insurance, including for the 2016 tax year.

— Reporter: 541-383-0304,

tbannow@bendbulletin.com