Baker City hotel offers glimpse of the cowboy lifestyle

Published 6:05 am Thursday, March 30, 2017

- As the feed truck approaches, bison hurry through late-season snow for their meal. “They eat about one-third less than beef,” said Shawn Durr, “and they have a buffalo robe to keep them warm. That’s the best insulation on the planet.”

BAKER CITY —

Brandon Clark reined Blaze, his young quarter horse, to the left across a sagebrush plain. Leo, his faithful border collie, and Brutus, a Catahoula-collie mix, pranced by his side.

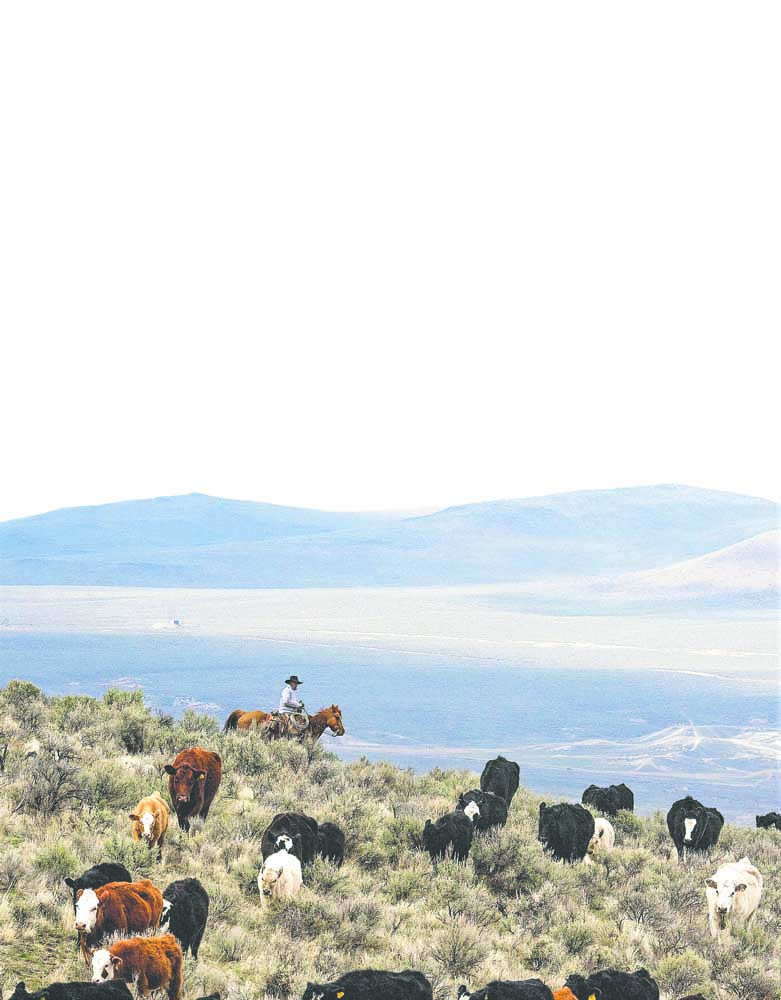

Clark waved at fellow cowhand Jeremy Johnson, riding on an upper slope of Virtue Flat, as the pair circled behind the 304 head of cattle they were herding toward higher-elevation grazing.

The beasts had spent the last month at an altitude of 4,000 feet, in the Ruckles Creek Draw some 20 miles east of Baker City. Now, in mid-March, Clark and Johnson — who work for the Powder River Valley’s sprawling Pickard Ranch — were moving the Herefords, Angus and Charolais up the draw to lusher meadows, recently soaked in winter snow.

Most of the cattle were compliant to the will of the herders, but there were a few stragglers. One cow and her calf, perhaps 6 months old, were increasingly separating themselves from others in the herd. The dogs knew their jobs. Circling, yipping, heel-nipping where necessary, the pair quickly had the wayward cattle hurrying to join the other cattle.

Had circumstances dictated, Clark was prepared to take the rope off his saddle and lasso runaways. It wasn’t necessary, but at one point he spun the lariat and roped a sagebrush — just to keep Blaze alert, he said.

Photographer Barb Gonzalez and I had front-row seats as we rode through the draw in a flatbed truck with Mandy Clark, Brandon’s wife.

A front-desk clerk for the Geiser Grand Hotel in Baker City, Mandy is the go-to person for the historic inn’s Eastern Oregon Ranch Experience, a program launched by hotel owner Barbara Sidway to give urban visitors a glimpse of ranch life.

“One of the things we hope to accomplish is to educate people,” Mandy said. “You can actually see first-hand what’s going on out here.”

Down on the farm

We began our ranch visit at the Clark home, a half-mile east of the Pickard Ranch headquarters near the unincorporated community of Keating. Mandy, who was raised at North Powder, between Baker City and La Grande, immediately took us to see her sheep.

The 18 ewes and a single buck are descendants of a trio of ewes she bought as a sixth-grader, more than 20 years earlier. Now, her two older sons — Lane, 13, and Colton, 9 — show them at 4-H events and fairs in Baker City, Halfway and Union. And 4-year-old Gage isn’t far behind.

The coats of these ewes are not the classic ivory-white of sheep bred for their wool. They are Suffolk-Hampshire crosses Mandy raises for meat, not for fleece. Most of the 17 infant lambs we met on our visit are destined to be on dinner tables within a year. Darling though they were, climbing on a hill of hay bales and dashing awkwardly across their pen, they’re not creatures to which a farm family will get emotionally attached. Mandy said she’ll keep five of them as breeding ewes, along with one buck, and sell the rest for their meat between the ages of 5 and 12 months.

The Clarks’ other animals included horses and a Shetland pony. Two of the horses, nephews of world-class bucking horse Lunatic Fringe, will be trained to buck — as will the pony, Mandy said.

We left the Clark homestead for ranch headquarters, detouring through meadows where cows grazed with their newborns. We watched as one still-wet calf struggled to stand for the first time, initially extending its rear legs into a “downward facing cow” position, then putting weight on its elbow joints before rising unsteadily on all fours. Ten minutes later, the newborn was following mom across the field.

These were early spring calves; most are born in May or June, Mandy said. They’ll grow quickly. By the time they reach maturity at a year and a half, they’ll weigh between 1,000 and 1,500 pounds, she said.

Ranch work

Brandon met us at the Pickard feedlot, where he moved a couple of dozen young cows through an adjustable cattle restrainer for inoculations, branding and “cutting.” As they were held tightly in a device designed to calm them, the ranch hand gave each one a three-times-a-year vaccination against brucellosis, leptospirosis and other common bovine illnesses. Another shot served a worming function.

Not all the animals got off so easily. A handful had the Pickards’ “T Lazy T” brand burned into their left ribcage with an electric branding iron. The sizzle of the cowhide and smolder of the thick hair is something that makes many urban visitors uncomfortable, both Clarks agreed.

But even visitors who could observe the branding didn’t want anything to do with the “cutting” — that is, the castration of male animals for breeding control. Only a few calves are kept as bulls; others become steers, as it’s common knowledge in the industry that low testosterone levels assure high-quality beef. I watched, somewhat timidly, as Brandon reached under the immobilized cows, stretched their scrotums and clipped off their testicles with a minimum of bloodshed.

By mid-April, Mandy said, cowboys and ranch hands will be gathering for the more formal branding season. “They’ll do 300 head in a day,” she said, as they rope the calves by heads and heels, then stretch their bodies for shots, branding and cutting. “They can get it done in no more than a minute apiece,” she said. “The faster you get it done, the less stress on the cow.” After a couple of weeks’ recovery time, the cattle will be turned out for grazing.

Everyone looks forward to this time of year, she said: “In a cowboy’s life, branding season is the highlight. You get to hang out with friends whom you haven’t seen all winter. The weather is usually good, and you’ll get together for dinner and beers.”

In the meantime, Mandy said, it’s fence-mending season. And there’s plenty of work after the recent harsh winter. “Elk knocked down a lot of fences this year,” she said. “They are brutal on fences. They run straight into them.”

In addition to breeding cattle, the Pickard Ranch grows the grain to nourish its animals — alfalfa, corn, barley and hay grass. It makes economic sense in a tough business, Mandy said. “Most ranchers run on an operating loan from the bank,” she said. “Many ranches have to keep rolling it over, and it can snowball in a hurry.”

Where buffalo roam

The Pickard Ranch doesn’t breed buffalo. But the Durr Ranch does.

David Durr, 84, is a retired electrician who once wired both the Geiser Grand Hotel and the historic Sumpter Valley Gold Dredge. Today, assisted by his son, Shawn, he owns and operates the Oregon Trail Bison ranch outside tiny Halfway.

Oregon Trail Bison isn’t a tourist attraction. It’s a working ranch that sells whole animals for $2,500 a head. Buffalo meat, after all, is considered by many connoisseurs to be leaner and healthier than beef. David Durr said he raises all of his bison without growth hormones.

The Durrs invited Gonzalez and I to join them on their Pine Creek spread one morning. Shawn loaded the back of a flatbed with bales of hay, and the five of us — that’s including Shawn’s border collie mix, Magi — headed out onto the Durrs’ 600 acres to feed the herd of just under 200, including several calves born last spring.

Dave said he prefers bison to cattle because they’re easy to manage. “Cattle give you a lot of work but no bucks,” he said. “The buffalo, I get ’em up once a year and worm ’em. The rest of the year, I leave ’em to themselves.”

There wasn’t a lot to the feeding process. As Dave pulled the flatbed behind a truck cab, and Magi instinctively herded, Shawn tossed patches of hay into the pasture. He supplemented it with a mineral salt block.

“It takes three years for a buffalo to put on the weight that cattle will gain in a single year,” Shawn said. “They eat about one-third less than beef, and they have a buffalo robe to keep them warm. That’s the best insulation on the planet. They don’t even seek out shade in the summer.”

Calves grow until they’re about 8 years old, Shawn said, but may start breeding as young as 3. They can live 40 years. But on a ranch like Oregon Trail Bison, there are unwritten rules when it comes time to thin the herd, as the Durrs did in recent months.

“There’s always a reason when it comes to choosing which to butcher,” he said. “Some animals start jumping over the fence. Others show too much aggression. They give us reasons.”

Delivering the West

Halfway is a community of fewer than 300 people that is actually about halfway, in driving time, from Baker City to the Hells Canyon Dam put-in for Snake River raft adventures.

It’s also a takeoff point for pack trips into the Wallowa range’s Eagle Cap Wilderness from the old mining settlement of Cornucopia. Its marketing slogan is: “Halfway to Heaven, Halfway to Hell.”

There’s limited lodging and dining in Halfway, which is 55 miles east of Baker City via State Route 86. Most visitors find it convenient to stay in Baker City, which was the most important city between Salt Lake City and Portland when the Geiser Grand Hotel was built in 1889.

“We can deliver the West to people who are looking for it,” said Sidway, a leader in the national historic-preservation movement. With her husband, Dwight, she bought and revitalized the once-derelict hotel in 1993. Located in the heart of downtown, it now has 30 rooms, a fine-dining restaurant and lounge, and a loyal clientele.

“We had been working on the Ranch Experience concept for 2½ years,” she said. “It was originally inspired by a pair of French journalists, from Le Figaro, who wanted to do some cowboy stuff. But last year’s Malheur occupation led us to roll it out.”

Sidway said she found the Ammon Bundy-led takeover of the Burns-area wildlife refuge to be “transformative. I became acutely aware of the biggest chasm of understanding that I’ve ever encountered.” In following the incident, she said, she grew to better comprehend “the deep challenges for ranchers, who are a critical part of our culture.”

Unlike traditional farmers, Sidway said, “Ranchers are risk takers. They gamble on what they will get for their animals. There’s a lot of flash and glamour at the heart of ranching. But it’s risk versus reward.”

Since the program began a year ago, many visitors have been paying $39 per person to spend their morning or afternoon hours exploring a cattle ranch or feeding buffalo. Last year’s first customers, Sidway said, were urban newlyweds on their honeymoon. “People ask questions, and ranchers answer them,” she said. “We can see a bit of closing of the understanding gap.”

The Oregon Trail

The first settlers came to Baker County on the Oregon Trail. Beginning in the early 1840s, travelers en route to the Willamette Valley saw the potential of farming the broad Powder River Valley. Some later returned to homestead, and by 1865, Baker City had been platted as a city. Ranching has been a mainstay of the economy for more than 150 years.

The story of the earliest white arrivals to the valley may be experienced at the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center. Located atop Flagstaff Hill overlooking the valley, its life-size dioramas help visitors understand the enormous courage and tenacity shown by the many thousands of Americans who followed the trail. They kept coming until the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, easing the burden of overland travel.

At the interpretive center, managed by the Bureau of Land Management, visitors can enjoy films, living-history programs and other special events, or they can hike on a 4-mile system of interpretive trails to visit remnants of a historic gold mine and see where wagon ruts crossed the arid plain. From a circle of covered wagons, the forested Blue Mountain may be seen to the northwest, assuring emigrants that the end to their long journey was rapidly approaching.

In the other direction, to the southeast, is Virtue Flat, where I had traveled with my cowboy companions as they rounded up the Pickard herd. Looking from the Oregon Trail center, sharp-eyed observers might discern nearly 7 miles of wagon ruts extending through this apparent wasteland. Here, emigrants once fought through shoulder-high sagebrush, never imagining they were laying the groundwork for 21st-century ranches.

— John Gottberg Anderson can be reached at janderson@bendbulletin.com.

Expenses for two

Mileage, Bend-Baker City (round-trip): 462 miles at $2.40/gallon: $44.35

Lodging (two nights), Geiser Grand Hotel: $233.26

Dinner, Palm Court, Geiser Grand: $70

Breakfast, Coffee Corral: $18

Tour cost, ranch visits: $78

Lunch, The Main Place: $24

Dinner, Barley Brown’s: $59.75

Breakfast, Lone Pine Cafe: $32

Admission, Oregon Trail center: $10

Lunch, Sumpter Junction: $23.07

TOTAL: $592.43

If you go

(All addresses in Oregon)

INFORMATION

Baker County Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau: 490 Campbell St., Baker City; visitbaker.com, 541-523-5855.

Baker County Tourism: P.O. Box 861, Baker City, OR 97814; basecampbaker.com, 800-523-1235.

HOTELS

Geiser Grand Hotel: 1996 Main St., Baker City; geisergrand.com, 541-523-1889, 888-434-7374. Rates from $99. Palm Court Restaurant serves three meals every day; moderate to expensive.

Oregon Trail Motel: 211 Bridge St., Baker City; oregontrailmotelandrestaurantbakercity.com, 541-523-5844. Rates from $39. Restaurant serves three meals every day; budget and moderate.

Pine Valley Lodge: 163 Main St., Halfway; pvlodge.com, 541-742-2027. Rates from $45.

RESTAURANTS

Barley Brown’s Brew Pub: 2190 Main St., Baker City; barleybrowns.com, 541-523-4266. Dinner Monday to Saturday. Moderate.

Coffee Corral: 1706 Campbell St., Baker City; facebook.com, 541-524-9290. Breakfast and lunch every day. Budget.

Latitude 45 Grille: 1925 Washington Ave., Baker City; facebook.com, 541-406-4545. Dinner Tuesday to Saturday. Moderate.

The Lone Pine Cafe: 1825 Main St., Baker City; facebook.com, 541-523-1805. Breakfast and lunch most days. Budget and moderate.

The Main Place: 146 Main St., Halfway; facebook.com, 541-742-6246. Three meals Tuesday to Saturday. Budget and moderate.

Sumpter Junction Restaurant: 2 Sunridge Lane, Baker City; sumpterjunction.com, 541-523-9437. Three meals every day. Moderate.

ATTRACTIONS

Copper Belt Winery: 1937 Main St., Baker City; copperbeltwinery.com, 541-519-4740.

National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center: 22267 state Highway 86, Baker City; oregontrail.blm.gov, 541-523-1843. Open every day. Adult admission $5 winter, $8 summer.

Oregon Trail Bison: 45532 Crow Road, Halfway;.www.oregontrailbison.com, 541-742-4011.