Director and producer elevated Los Angeles theater to prominence

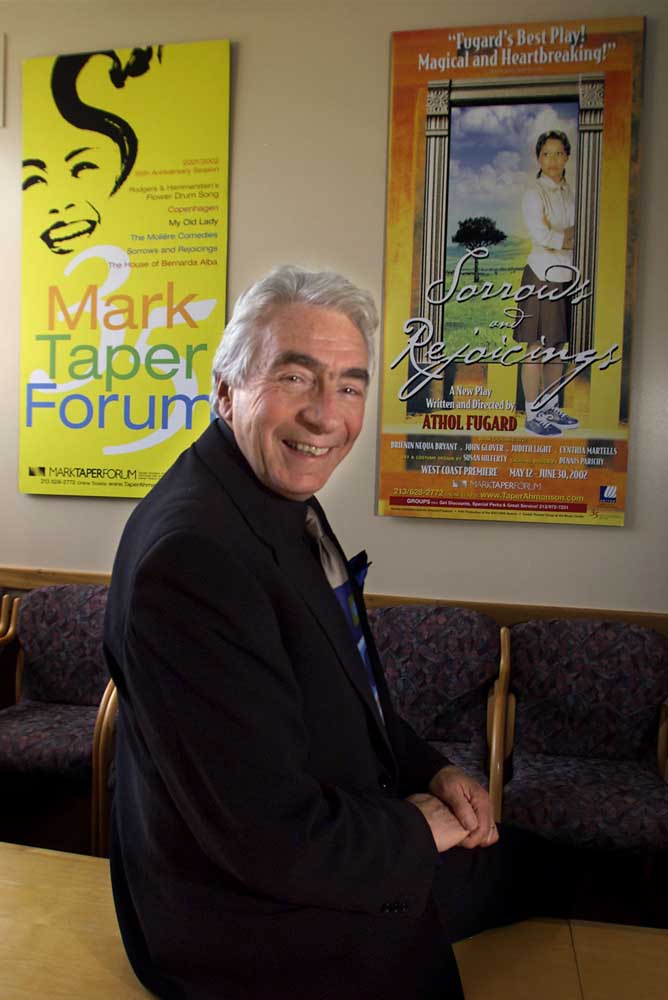

- Carlos Chavez / Los Angeles Times via Tribune News Service file photoGordon Davidson, artistic director and producer for the Mark Taper Forum and the Ahmanson Theatre, in the conference room near his office in Los Angeles.

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, October 5, 2016

LOS ANGELES — Gordon Davidson, the Center Theatre Group impresario who launched, defined and for 38 years personified Los Angeles’ flagship theater, the Mark Taper Forum, has died, his family said. He was 83.

Davidson died Sunday night after collapsing at dinner, said his wife, Judi Davidson.

Starting in 1967, Davidson’s artistic vision, professional connections and business savvy were indispensable in transforming L.A. from a passive backwater where theatergoers largely consumed the Broadway touring shows to a wellspring for new works that won Tony Awards and Pulitzer Prizes. He directed more than 40 plays and produced more than 300 works for the Center Theatre Group, and he relished the spotlight as L.A. theater’s most prominent public face until his retirement in 2005.

As Gil Cates, producing director of the Geffen Playhouse, once put it, “He was the Moses of theater in Los Angeles.”

“His whole body of work at the Taper made me feel it was the place to go,” actor Alan Alda said in 2004, as Davidson prepared to step down. “He puts on plays that are entertaining, that tickle your mind, that have substance.”

In 2001, Davidson directed Alda as physicist Richard Feynman in Peter Parnell’s “QED.” Having seen the Taper’s boss in action over the six years it took to create, Alda said, “as far as I can tell, he does theater from the breakfast table all the way through to the midnight snack.”

Michael Ritchie, artistic director of Center Theatre Group, on Monday recalled Davidson’s personal grace and sense of community, which he said grew over the 35 years they knew each other.

“Gordon was one of the few who made a conscious decision to focus on new plays and unheard voices,” Ritchie said, calling Davidson a visionary.

Oskar Eustis, artistic director of the Public Theater in New York, recalled being flabbergasted in 1989 when Davidson offered him the job as the Taper’s associate artistic director, a position he held until 1994.

“Gordon made a claim that theater was a place not to just reflect America, but to expand our idea of America,” Eustis said, pausing frequently to compose himself after the news of his mentor’s death. “He did that with a showman’s flair, a zest for life and the unwavering support of artists he believed in.”

Among Davidson’s personal signatures were inexhaustible energy, a willingness to let theater virtually subsume his life, and a natural warmth and amiability that helped him forge connections with audiences and performers. He relished stories that embodied timely political and social issues, and he had an entrepreneur’s enthusiasm for the deal-making that brought coveted plays and star actors to the 745-seat Taper and the 2,100-seat Ahmanson Theatre. Davidson realized a long-deferred dream in 2004 with the opening of the 315-seat Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City as a home for new and experimental plays.

Davidson and the Taper grabbed attention with their first show, “The Devils,” which ruffled some sensibilities with its erotic depiction of Catholic clergy in 17th century France. Local fascination soon turned to national acclaim with “In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” about the moral stakes for scientists working on the atomic bomb, and “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine,” documenting the legal aftermath of a 1968 protest against the Vietnam War draft. Davidson took both shows to Broadway, signaling to an impressed theater establishment that something important was afoot in Los Angeles.

“Mr. Davidson is doing some of the most valuable theater work in the country,” the late New York Times critic Clive Barnes wrote in 1970.

Davidson’s sweetest night of personal laurels was the 1977 Tony awards, when he won best director honors for his staging of “The Shadow Box,” Michael Cristofer’s play about hospice patients, and the Taper won for outstanding regional theater.

Mark Medoff’s “Children of a Lesser God” was another big hit Davidson directed on Broadway after its Taper premiere in 1979. The show about a deaf woman and her teacher ran for more than two years on Broadway and its two lead players, John Rubinstein and the deaf actress Phyllis Frelich, won Tonys.

“He created an atmosphere in rehearsal that asked for everyone’s input, promoted everyone’s very best; he would go into whatever dark corner or step onto any precipice with a writer,” Medoff said by email Monday. “My times with Gordon — or Moose, as I called him — were precious and ever illuminating. He loved the work; he loved the people who created the work, and though he was one of the most consequential producers of the living writer in the latter half of the 20th century, he was a man of extraordinary humility, grace and kindness.”

In 1978, Davidson and the Taper broke ground with “Zoot Suit,” by Luis Valdez, for the first time exploring the denial of justice to one of L.A.’s minority communities, Mexican Americans during the 1940s.

But the 1980s found Davidson and the Taper absorbing more salvos than plaudits. Liberal activism had given way nationally to a cheerful conservatism, personified by Ronald Reagan, and Davidson struggled to find a coherent direction for his company.

“The cord that was there in the ’60s between the Taper and its audience, when the Taper knew what it was, is no longer there,” Joseph Stern, executive producer of the television series “Law and Order” and leader of L.A.’s Matrix Theatre, said in 1987. “Now their political work makes statements for statements’ sake.”

In the early 1990s, the Taper rebounded: It was instrumental in launching Robert Schenkkan’s “The Kentucky Cycle,” with its dark portrayal of American history, and “Angels in America,” Tony Kushner’s landmark “gay fantasia” about the AIDS epidemic. The two six-hour-plus epics both were staged at the Taper in 1992 — and won back-to-back Pulitzer Prizes in 1992 and 1993, the first plays to receive that honor without a New York staging.

Never shy about playing the front man, Davidson was in his element jumping on the stage before a show for greetings and announcements, or leading a post-play discussion. He was a caricaturist’s delight, a tall, stoop-shouldered captain with a helmet of wavy, untamed hair that was ever bushy but whitened over time, and prominent eyebrows that stayed stubbornly black.

He could show an impatient, steely side with his staff, but lieutenants who recalled verbal cuffings over details they’d neglected also appreciated his demanding tutelage, and some went on to top positions elsewhere, including Kenneth Brecher, former executive director of the Sundance Institute.

Davidson was born in Brooklyn, New York, on May 7, 1933, the first of three sons of Alice Gordon Davidson, who played the piano, and Joseph Davidson, a Brooklyn College drama professor.

Davidson’s passion as a teenager was science and mathematics; he entered Cornell University on a full scholarship, planning to become an engineer. But a part-time job with a General Electric unit that designed controls for guided missiles sent him fleeing to the theater department. He earned a master’s degree in theater from Western Reserve University in Cleveland (now Case Western Reserve) in 1957. A year later he began working as stage manager at the Phoenix Theatre Company in New York and the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut, where he was a $40-a-week assistant to the company’s leader, actor-director John Houseman, and he married Judi Swiller, a Vassar College graduate who went on to become a leading theatrical publicist in L.A.