Traces of Valley Fever fungus found in Central Oregon

Published 12:00 am Thursday, July 28, 2016

- Traces of Valley Fever fungus found in Central Oregon

Public health officials have thought for decades the coccidioides fungus that causes Valley Fever was found only in the Southwest. The vast majority of cases have been diagnosed in residents of Arizona, California or neighboring states, or in individuals who had recently traveled to those regions. Then, in 2014, the confirmation of three cases of Valley Fever acquired in Washington state launched a search for the fungus throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Now soil samples from two sites in Central Oregon have tested positive for cocci DNA, raising the possibility that local residents could be at risk of contracting the condition without traveling to what had been considered its endemic areas.

Trending

“It didn’t just jump from California to Washington and miss Oregon,” said Dr. Emilio DeBess, a public health veterinarian with the Oregon Health Authority. “We know it’s here.”

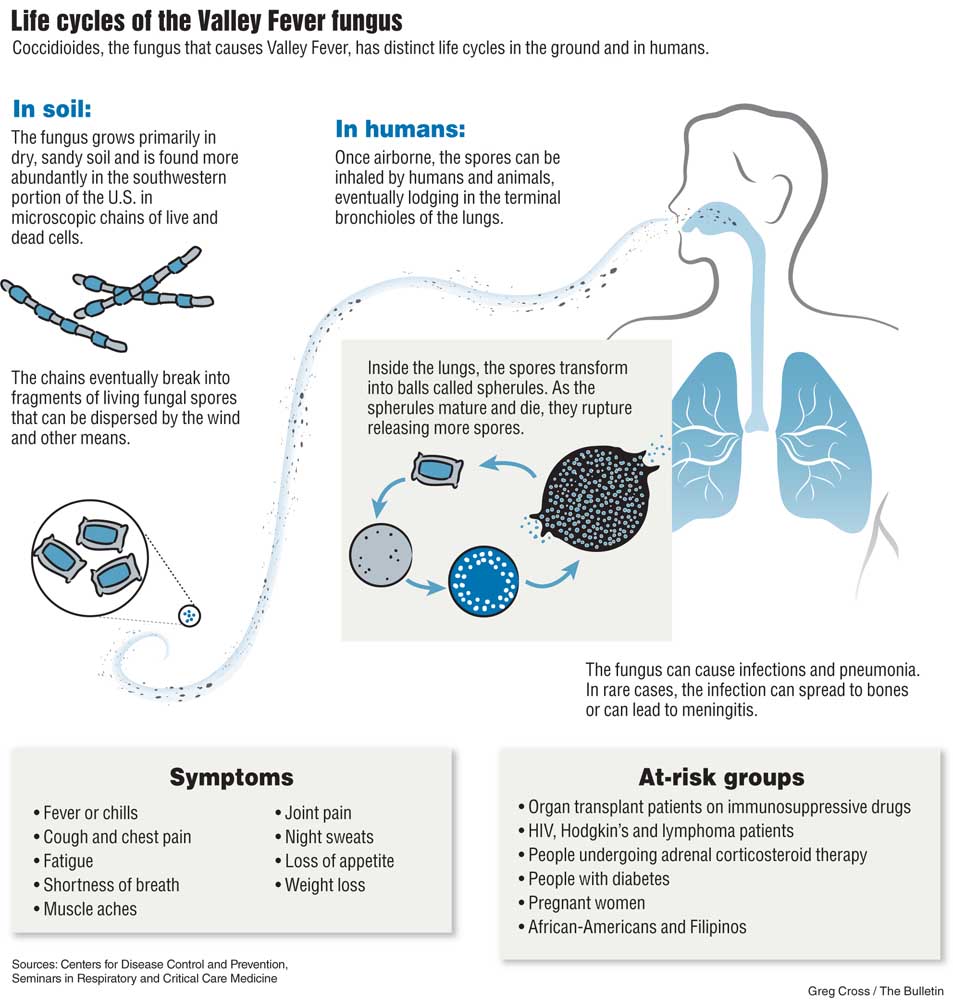

Valley Fever, or coccidioidomycosis, is usually caused by the inhalation of fungal spores that lodge deep in the lungs, where they grow into spherules each filled with tiny spores. Eventually the spherules burst open, each spreading a hundred or so spores through the lungs causing inflammation and other damage.

The fungus grows in dry, sandy soil and can remain dormant during long dry spells as long filaments that break into airborne spores when it rains. The spores can be swept into the air during dust storms or with the disruption of soil during construction or farming.

The condition was named after the San Joaquin Valley, where in 1977 more than 100 residents were infected with Valley Fever — and six died — after a major windstorm coated the southern end of the valley with dust. From 1998 to 2014, the number of individuals diagnosed with Valley Fever in the U.S. has ranged from less than 2,300 to more than 22,000. Three out of five infected individuals will have no symptoms, and most of the remainder will experience a flu-like illness characterized by fever, cough and exhaustion. Experts believe thousands more cases may be overlooked or misdiagnosed.

Some 2 to 4 percent of patients will see the disease spread to other parts of the body, causing an infection in the bone or meningitis if it travels to the brain.

Skin tests done on some 110,000 Navy recruits, college students and student nurses in the 1940s and ’50s set the endemic region from the southern tip of Texas through New Mexico, Arizona and the southern portions of Utah, Nevada and California. But researchers had no way of testing the soil for the fungus directly.

Trending

“Because of the limited ability we had to be able to sample the environment and find it, we haven’t been able to look at the frontiers to see how far it might be expanding,” said Dr. Tom Chiller, deputy chief of the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When patients developed Valley Fever in states outside the traditional area, doctors generally assumed it was linked to travel. But in 2010, the Washington State Department of Health identified three patients who lived near the intersections of Benton, Franklin and Walla Walla counties with no recent travel history.

“It got us thinking, why couldn’t the fungus be up there?” Chiller said.

Even though there was no way to test the soil for the fungus, Chiller had the foresight to recommend that Washington officials collect samples from the areas where they suspected the infection occurred.

One of the patients had reported regularly digging in a dirt canyon on public land near a residential complex. Another developed a cocci wound infection after falling from his all-terrain vehicle on a dirt track in a public park, and was able to show the authorities precisely where he had fallen.

In 2014, Phoenix-based Translational Genomics Research Institute developed a test that could find bits of cocci DNA in the soil. Both the stored samples and fresh samples taken from the sites tested positive. Health officials were then able to isolate the fungus from the soil samples and sequenced the genomes to compare it with the sample taken from the ATV rider’s leg.

“They were a genetic exact match,” Chiller said. “Now we had it. We had the smoking gun.”

The strains were similar to those in the San Joaquin Valley but had undergone some evolution. It suggested the fungus had likely been there for a while.

“That’s when I began to reach out to states in the area,” Chiller said. “It didn’t just jump over Oregon.”

The search continues

Once the positive soil tests were confirmed in Washington, DeBess began contacting veterinarians in Eastern Oregon, collecting animal serum from any dogs that had symptoms consistent with Valley Fever. One of the samples tested positive but was eventually attributed to the owner’s travel to Arizona.

At the same time, DeBess began to collect soil samples around Central and Eastern Oregon, looking for dry, sandy soil in which the fungus seems to thrive. Only two sites turned up positive: one between Bend and Redmond, and another between Bend and Brothers.

In early July, DeBess and a representative from the CDC returned to Central Oregon broadening their search around the area where the initial positive samples were found.

“The plan is to have 60 samples to send down to CDC, and if we have (positive) results, we’re going to increase that circle, go a little further out,” DeBess said.

If any soil samples test positive, CDC lab technicians will try to isolate and grow the fungus from the sample. That would provide the same type of smoking-gun evidence public health authorities used to determine cocci was present in Washington state.

“It’s super challenging,” Chiller said. “If I go to Arizona where it’s supposedly hyperendemic and take 100 soil samples, I may not get one positive. It’s a bit of a needle in a haystack.”

Health officials say their goal in testing is mainly to raise awareness, particularly among doctors treating patients with pneumonia.

“I’m worried about undiagnosed disease — that’s when we get into trouble,” Chiller said. “These patients in Washington, for example, had pretty severe disease, probably because they weren’t diagnosed early enough.”

So far, Oregon public health officials have identified 18 individuals with cocci infections, although all of those cases appear to be linked to travel. It’s completely plausible, the experts say, that individuals in Central Oregon have been infected but had no symptoms, or that their infections were misdiagnosed.

“It’s commonly mistaken for community-acquired pneumonia, even by people who should know better,” said Dr. Jon Lutz, an infectious disease specialist with Bend Memorial Clinic.

Oregon public health officials are working with Lutz to develop a program to test pneumonia patients in Central Oregon to see if they might have a cocci infection. In Arizona, one out of every three cases of community-acquired pneumonia is caused by the fungus. The rate is not likely to be nearly that high in Oregon.

“We assume that the community-acquired pneumonia will not yield a lot of good information,” DeBess said. “But we have a lot of dogs out here. Animals are closer to the soil, so dogs are potentially more likely to give us the information we need.”

Explaining the spread

It’s unclear whether small amounts of the cocci fungus have been in the Pacific Northwest all this time, or whether it represents a more recent spread. Winds can carry spores for hundreds of miles at a time, so it’s possible the fungus has been blown here over the decades.

“We’ve always wondered whether there was a relationship with some sort of a desert rodent,” Chiller said.

There’s some, mostly anecdotal, evidence that it’s more likely to get a positive test around a rodent burrow hole. Is that because rodents actually carry the fungus or just because they spent a lot of time in the dirt? The experts aren’t sure.

Researchers are now doing more sampling around rodent holes throughout the Western U.S., looking at differences between newer and older burrows, active and abandoned ones. If they can find a connection, they would then start trapping rodents to see if they play a role in its spread.

The search is complicated by questions over the meaning of a positive test. Soil can test positive one day and negative the next. Testing can identify minute quantities of fungal DNA, some of which many not even be alive anymore. And the soil is full of different microorganisms that could potentially lead to false positives. That’s why researchers won’t confirm cocci’s presence unless they can isolate and grow the fungus from a soil sample.

“My gut feeling is we’re going to find it,” Chiller said.

A burdensome disease

Many people discount the impact of Valley Fever, perhaps because so many have no symptoms and the vast majority will recover eventually. But even symptomatic patients who avoid the worst complications see their lives turned upside-down by the condition.

“The simple uncomplicated cases are often ignored as sort of a flu-like illness. It’s anything but that,” said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center of Excellence. “People are literally away from works for weeks to months, because they can’t get out of bed.”

Treatment is often delayed because doctors see pneumonia and prescribe antibiotics. It’s only when the patient doesn’t improve that they begin to consider a fungal cause.

Other patients are told they have cancer, until a biopsy shows that it’s actually Valley Fever.

“It often takes weeks if not longer with a lot of testing and CT scans and eventually tissues samples to figure out what’s going on,” Galgiani said. And by that time, the disease may have progressed.

Juanita Priest, a 66-year-old writer from Portland, contracted Valley Fever after she was caught in a dust storm in Phoenix in 2005. Despite numerous hospitalizations after her initial infection, it wasn’t until a relapse years later she was finally diagnosed. She still deals with chronic, debilitating fatigue, and her doctors routinely monitor the lesions on her lungs so they can quickly intervene if they start to grow. Usually, that means a dose of fluconazole, an antifungal with a reputation for nasty side effects.

“It’s like antifungal chemo almost,” Priest said. “You hair falls out; your lips crack; sometimes you get rash. It really puts you down for a long time.”

What’s more, doctors aren’t sure whether it really makes a difference. A clinical trial is underway in Bakersfield, California, to answer that question. But doctors believe that at best, the antifungals available can suppress the fungal infection, not clear it from the body. That means many patients may have to be treated for the much of their lives.

Galgiani believes he may be sitting on an actual cure.

An antifungal called Nikkomycin Z was discovered by a major drug company in the 1970s. Made by a bacteria, the drug acts by blocking the enzyme chitin, which is a crucial building block in fungal cell walls. Humans don’t make chitin, so the drug should have little toxicity for people. But when the company went out of business in 2000, clinical development of the drug stopped.

A small foundation in California tried to find another drug company to take over, but after five years of fruitless effort, Galgiani’s Valley Fever Center took over.

“No other antifungal has the same mechanism of inhibiting the fungus,” he said. “We think the data in mice suggests it can cure the disease, as opposed to suppress it, which is what current treatments do.”

So far less than a dozen individuals have received a single dose of Nikkomycin Z, but the center needs to make more of the drug before it can proceed to clinical trials.

“Thus far, the only thing that’s slowing up its further testing in humans is investment,” Galgiani said.

The National Institutes of Health has granted some $6 million to support its development, but setting up a manufacturing system and running the drug through clinical trials would be much more costly.

At only 150,000 potential patients each year, Valley Fever is considered an orphan disease. The drug wouldn’t offer the same type of profits as drugs for cholesterol or high blood pressure that must be taken for a lifetime.

Galgiani has co-founded a business, Valley Fever Solution, that is actively seeking from a drug company or a venture capitalist willing to put up the dollars to test the drug.

“It’s a small market, but we do think there is a business model,” he said.

Work on a potential Valley Fever vaccine has also stalled after research funding dried up.

Communicating risk

If tests find cocci in Oregon, it could spur greater attention to the disease, uncovering more potential patients and more confirmed cases. That could also bring new advocates among public health and government officials seeking a solution.

Many Valley Fever patients argue public health authorities should do more to warn residents and travelers about the risks. Seattle resident Sharon Filip, 71, contracted Valley Fever in 2001 while visiting her son in Tuscon, Arizona.

“You hear about monsoons; you hear about the scorpions; they have snakes in the desert — but nothing was ever mentioned about Valley Fever,” she said. “None of us were aware it existed.”

Within a week of coming back to Seattle, she got severely ill.

“It was like falling off a cliff,” she recalled. “One day I was fine, and the next day, I couldn’t get my head out of my pillow.”

Doctors tried to treat her pneumonia with antibiotics, but Filip continued to get worse. The fungus had spread to her brain causing meningitis.

“My brain was pulsing like it was trying to come out,” she said. “It was severely painful. You have tears coming down your face.”

Eventually doctors took a sample of fluids from her lungs and diagnosed her with Valley Fever.

Her son, David Filip, a freelance writer, began to research the condition, and they published a book, Valley Fever Epidemic, that many patients refer to as their Cocci Bible. They’ve also launched an informational website, ValleyFeverSurvivor.com, and have more than 1,000 patients in a closed Facebook support group.

The Filips have been urging public health authorities to be more outspoken about the risks of Valley Fever and to reveal what sites have tested positive for cocci. They were particularly dismayed when officials in Washington state wouldn’t provide information where the positive soil samples were found.

“Shouldn’t people have the right to know what could happen to them if they go into a particular areas?” she asked.

Chiller said it’s up to state agencies to determine how much detail to provide about where the positive soil samples were found. But he argues the actual site might not be what’s important.

“I can go to Arizona and sample an area that I know has cocci and not find it,” he said. “So what I’m worried about is not so much the over interpretation of the positive, but maybe an over interpretation of a negative.”

It might be more helpful, he suggested, to let people know there’s a risk throughout the county, rather than to mislead them to thinking the risk is contained in just a few spots.

DeBess said Oregon officials are more likely to talk about even broader regions of risk.

“We would probably say this could potentially be a problem in Eastern Oregon, period,” he said. “It’s city-related; it’s not county-related. It’s all over.”

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com