Dying vet gets one last ride on Harley

Published 12:00 am Friday, June 10, 2016

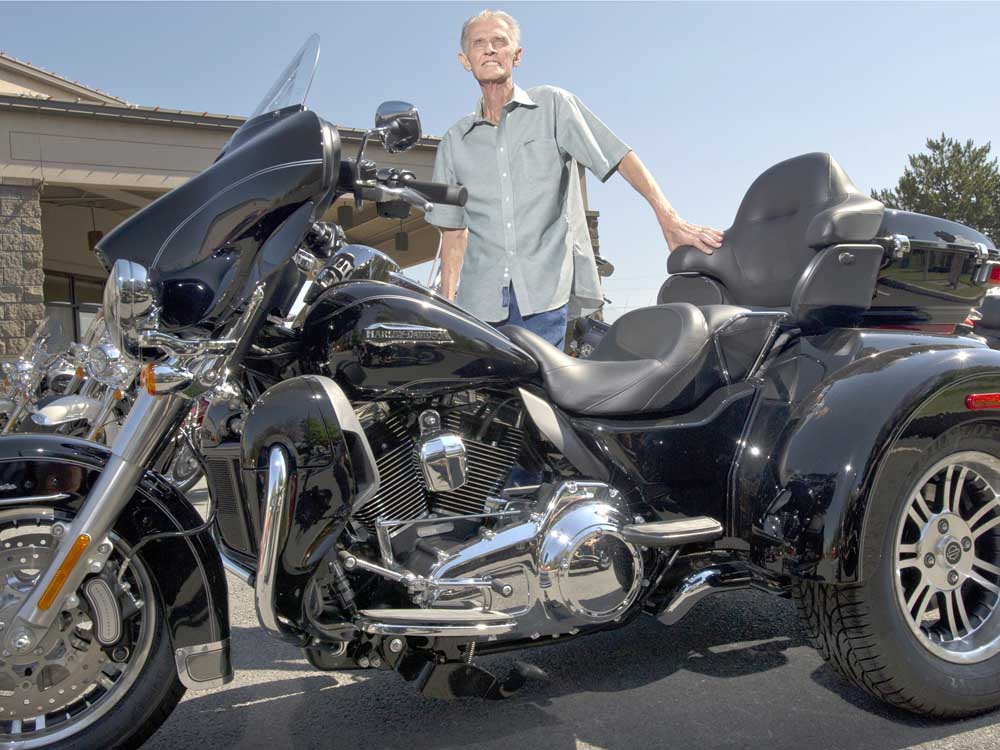

- Ryan Brennecke / The BulletinJim Moyer, 69, stands by the Tri Glide Ultra that Wildhorse Harley-Davidson in Bend let him ride after getting a six-week prognosis to live.

When Jim Moyer revved the 103 cubic-inch engine of the ink black Harley-Davidson tricycle, the syrupy purr was enough to distract him from the six-week prognosis his doctor has given him to live.

A veteran suffering from terminal cancer, Moyer, 69, recently took advantage of the numerous promotions Wildhorse Harley-Davidson extends to veterans and service people. The ailing vet wanted to ride a Harley one last time.

“I needed that rumble in my butt one more time,” Moyer said.

In the instance of Moyer, the local dealership let him roll out a motorcycle — free of charge — for a pleasure ride.

On a recent afternoon, Moyer idled at a crosswalk in downtown Bend. When the light turned green, he cranked the throttle, flushing the engine with oxygen, fuel and fire. The act unleashed the trademark thunder, and his wide grin flashed in the chrome-rimmed rear-view mirrors.

“The Harley sound means the open road, freedom,” he later said.

A few weeks later, Scott Dumdei, who handles sales and finance at Wildhorse, had visited Moyer and his wife Sue at their tidy home.

Dumdei, 45, has known Jim Moyer for 30 years; he first met him at the Western Tool Supply company, which he managed. At the time, Moyer was a maintenance manager and designer at Nosler, the ammunition company, and was a regular customer. Dumdei, then in his mid-20s, said he looked up to Moyer as the cool older guy; his employees respected him, and he was a “solid, stand-up guy who was all about business.”

The two maintained a cordial business relationship, later discovering they shared a love of motorcycles.

Sitting in the Moyers’ living room, Dumdei described how pleased he was to see Moyer walk into Wildhorse — where Dumdei has worked for five years — several months ago.

Moyer told Dumdei he’d recently undergone several chemotherapy treatments to combat the multitudes of tiny tumors growing in his intestines and lungs. The situation was serious, but he was still optimistic the chemotherapy would work and he would soon be strong enough to handle a motorcycle.

While Moyer grew up riding motorcycles, he hasn’t owned a bike since the early 1970s, when the responsibility of marriage and raising a family sidelined his love of the road.

‘Ghost rider’

At Wildhorse, Dumdei walked Moyer among the showroom’s fleet of bikes. He fixed his gaze on a pristine, purple Harley-Davidson Softail Deuce, for sale on consignment. With only 10,000 miles on it — impressively low for a 14-year-old bike — Moyer couldn’t imagine a more perfect machine.

“Every piece of chrome was exactly where I would have put it,” he said, adding that its two-seat configuration would accommodate his wife. Moyer envisioned how a detailer could apply flames and the words “Ghost Rider” to the tank. He said it would be fitting for him.

“I’m dying, I’m a ghost,” he deadpanned.

However, someone plunked down $8,400 for the Deuce before the veteran could buy it. In coming days, Moyer also learned his cancer was not responding to the chemotherapy; his oncologist recommended they let nature run its course. Moyer acquiesced. Informed of his deteriorating condition, Dumdei and Wildhorse co-owner Brandon Nash knew they had to act quickly; they agreed to let him roll out the shop’s brand-new jet-black Tri Glide Ultra, a three-wheeler.

“It had zero miles and they let me put 50 on it. Who would do that?” Moyer said, choking up. After he dabbed his eyes, he passed his wife a tissue and apologized — his medications make him extra emotional, an effect that compounds his compassionate nature, he said. Moyer said on the bike’s inaugural ride, which he took on Mother’s Day, he bought his wife flowers, which he stored in the trike’s trunk. Then he rolled through downtown Bend, intent on stopping at as many red lights as he could; a fine excuse to crank the throttle and feel the pure exhilaration.

A legacy indebted to veterans

Modern American motorcycle culture is rooted in World War II. Harley-Davidson — one of two American motorcycle outfits that scooted through the Great Depression — contracted with the U.S. military to supply troops abroad. Returning veterans snowballed their newfound love of motorcycling and need for camaraderie, often forming motorcycle clubs. In 1953, the Marlon Brando movie “The Wild One” capitalized on this subculture, ushering motorcycling — and the two-dimensional image of bikers as organized criminals — to the mainstream. Indebted to the originators who stoked the brand’s legacy, many Harley-Davidson dealerships operate veteran promotions. Wildhorse offers five programs, including the Harley-Davidson Military Program and the Wounded Warriors Project. A purple parking spot — colored for the Purple Heart Award — is reserved for veterans. That Moyer was permitted to pleasure-ride the tricycle is less the result of any particular program as it is the product of Wildhorse’s general regard for veterans — particularly terminally ill ones, Dumdei said.

Moyer enlisted in the military in 1965, receiving an honorable medical discharge in the same year after a mix of pneumonia and exposure to gas during basic training devastated his pulmonary system. In 1978, The Moyers moved from Pico Rivera, a city located in eastern Los Angeles County, to Bend. When oil mining ushered in a construction boom in Gillette, Wyoming, in the early 1980s, Moyer said he resisted the urge to relocate so he could be a “hot shot contractor,” and kept his family in Central Oregon, a place he was proud to call home.

An unguarded love

Moyer said the hardest part about his predicament is not being around to care for those he loves.

“You don’t want to leave your wife unguarded for 10, 15 years,” Moyer said. He and Sue, married for 49 years, were high school sweethearts who wed when they were 20 and 18 years old, respectively. Although Sue said she initially didn’t like Moyer because “he was too brash, too macho,” she eventually warmed to his swagger. “I got older and realized it was kind of cool — he’s a man,” she said with a giggle. The couple recounted the story of how Sue, still a teenager, gave Moyer all her savings so he could buy his first motorcycle, a Honda 250 which he would fully customize. Sue’s parents, however, “went berserk.”

“You saved up all that money and you gave it to some bum,” Moyer said. The couple, with wet eyes, laughed.

Moyer, who has “been tight with the Lord for over half his lifetime,” said he is not afraid to die. Now that he has hung on long enough to witness the birth of his granddaughter via smartphone footage, Moyer said he’s ready for God to take him from “this misery.” Moyer, who used to weigh 192 pounds a year ago, now tips the scale at 122. When he sits, he squirms with discomfort; extra skin, when it pinches under his pelvis, is painful, and he often sits on a pillow. “That’s what makes this so hard; I know he’s still strong,” Sue said, sitting alongside her husband. “He’s still him in his heart.”

One last ride

Dumdei said helping a friend get back on a motorcycle, even once, is something that makes his work meaningful.

“This is not just some line I like to use: I enjoy changing people’s lives,” said Dumdei, a five-year Wildhorse employee. “It’s worth more than money to me.”

When the reunited friends parted ways at the end of Moyer’s most recent visit to Wildhorse, the two men hugged. “Oh, buddy. Take care, now,” Moyer said, his jaw resting on his friend’s shoulder.

Asked what riding motorcycles has meant to him, Moyer was not short for words.

“A feeling comes over you, and it turns everything to light,” he said. “The bike brings you to life.”

— Reporter: 541-617-7816, pmadsen@bendbulletin.com