Mark Angel

Published 5:00 am Saturday, May 21, 2011

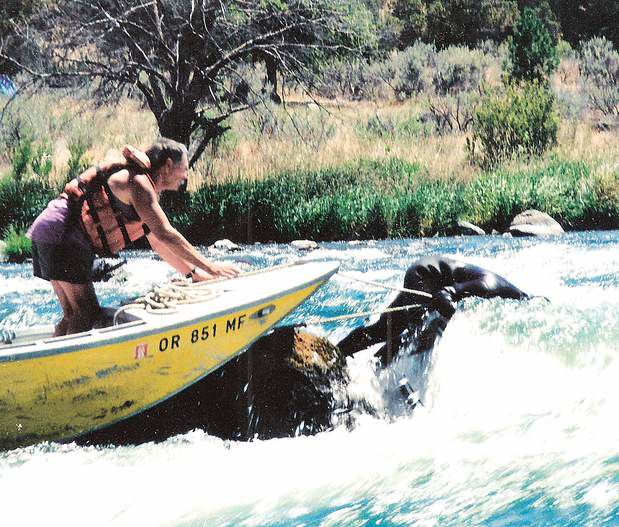

- Mark Angel at far right in a black wetsuit reaches beneath the surface on the Lower Deschutes River to rig a boat to pull up and salvage.

Wearing nearly 50 pounds in weights and breathing through a 50-foot hose, Mark Angel eased himself slowly down a ladder into the most notorious Class IV rapids of the Lower Deschutes River.

He had already tried three times to get in, but the high water raging through White Horse Rapids was bucking him like the meanest bull at the rodeo. The Redmond resident has been diving in rivers all his life but said he didn’t want to get in that water.

“I’d always dreaded diving off the face of that rock,” he said.

The torrent blasted him downward from the ladder. He had a split second to react and, not knowing what lay on the bottom, opted to hit knees first.

He heard a crack, and pain shot through his body. Angel had fractured his right tibia.

But four feet away from him was what he had come for. Ten days after 17-year-old Danielle Hagler disappeared, Angel had finally found the young woman’s body.

It’s what Angel does best — retrieving from underwater that which others have lost.

Angel’s day job is working for power companies, supervising the stringing and repairing of line across several states. It’s through his other business, White Water Salvage, that a half dozen times a summer he hauls up smashed drift boats from the depths.

Sometimes he’s hired for an unusual request, like the Florida man who asked him to locate his $15,000 Rolex watch in a 12-mile stretch of the Lower Deschutes. After a few astute questions, Angel managed to find it.

And once in awhile, he gets a call from a family or the coordinator of a search-and-rescue operation. For those he never accepts money.

“Mark is a living legend when it comes to the Deschutes River,” said Roger Pearce, who until recently was a sheriff’s deputy and coordinator of the Wasco County Search and Rescue. He retired this year.

“There is no one else that I know of who does what he does when it comes to whitewater diving,” Pearce continued. “In water that he feels fairly comfortable in, most guys come up and say, ‘Holy crap, I’m never going in that again.’ ”

It’s work Angel has trained for his whole life. And even at age 67 he doesn’t intend to quit anytime soon, even if it’s a family that calls.

“It’s pretty hard to say no because you know they have no other choice,” he said. “I’d rather be doing anything else.”

It’s work that he remains well-suited for at an age when others are into retirement. Lean and muscled from a lifetime of physical activity, Angel still rows, hunts, fishes and works long days on transmission lines in remote corners of the Northwest.

He lives on a spread east of Redmond with his wife, Judy, and their dogs. She has two adult children, as does he from a previous marriage.

Musing over coffee recently there, Angel said he was well into his 30s before he realized his skill might be unique.

At age 6, away from adult eyes, Angel would bounce his way through small rapids on the Feather River and Butte Creek near his childhood home in Paradise, Calif., for fun.

He soon managed to find a mask and fins. He stole the axle out of his sister’s tricycle, attached his mother’s broom and used the contraption to spear fish.

He also realized scanning the bottom that the river contained a trove of gear. Growing up poor, he saw opportunity and collected the rods, reels and lead to sell.

Angel enjoyed hunting on land as well as in the water. By his teens, being outdoors had become his passion.

“I’d hitchhike to go fishing or hunting,” he said. “I’d be standing 70 miles from home with a shotgun in hand, even at night, and always get picked up. It was a different time then.”

Angel tried scuba diving for the first time in his early 20s. A friend accidentally sank a new boat motor in 40 feet of water near the dock in a lake. The buddy bought scuba tanks and asked Angel for help.

“We’d watched ‘Sea Hunt,’ ” Angel said. “He didn’t know anything more about diving than I did.”

They recovered the motor, and Angel soon collected his own gear for going beneath the water’s surface.

He moved to Oregon in 1971 after a friend took him fishing on opening day near Maupin. He found work as a power company lineman, being transferred frequently around the state. But in his off time he kept returning to Central Oregon and its rivers.

He said he made a habit of rising before dawn to dive in the Lower Deschutes. He figured other divers would be there soon, too, and he wanted to be there first. He would haul up gear, clean it up and then bring it to a sporting goods shop in Portland for credit.

Finally, he realized there were no other divers coming.

“I dove for 20 years before I realized that nobody else did that,” he said.

Word about Angel’s river skills spread. Soon people were asking him to help pull boats from the water. A downed boat, even if destroyed by its battering against rock, is a navigational hazard and by law must be removed by its owner.

Finally, the day came when someone asked him to help find a drowning victim. A friend’s nephew went underwater in the Pine Hollow Reservoir in Wasco County, and search-and-rescue teams had been unable to find him.

He found the boy, and a precedent was set. More people would call.

Tools and gear

For his rescue work, Angel keeps a salvage yard’s worth of equipment.

He has an entire trailer devoted to diving gear, with rows of wet suits, coolers, regulators and buoys. Then there’s a metal barn filled with tools, welding equipment and partially finished projects.

He rolls up to a river scene with his 24-foot jet boat and a virtual garage full of tools and gear. The scuba equipment is from the ’60s and ’70s, as its lower profile causes less pull in the current.

He also brings knives used for working on hot power wires, winches for hauling boats from the deep and hot sticks, which are essentially long poles with a claw on the end also used to work on power lines.

The hot sticks are particularly useful, Angel said. He often probes the river with them and is able to tell the texture and sound of rock versus sand versus organic material. It can help him know where to go underwater and sometimes makes it unnecessary.

“I don’t give myself style points,” he said. “If I can do it without getting wet, then I’m a happy camper.”

He sometimes creates his own equipment. At his home, looking like a TV antenna for giants, is a massive metal structure Angel said will be a boom he will use to salvage boats. When finished, he believes it will handle 18,000 pounds.

Part of the method to his madness, friends said, is that Angel has the mind of an engineer and can build just about anything.

“The guy’s a genius,” said Taylor Geraths, a Bend fishing guide who often helps him on boat salvages. “His brain works so much faster than anybody’s I’ve ever met. When you have a tough situation, trying to figure out what to do, he’s two steps ahead of you.”

Pearce said he has been there at times when Angel assesses a situation and knows right then what contraption he needs to get the job done.

“I have a mechanical background,” Pearce said. “Yet sometimes I’ve wrinkled my eyebrows and said, ‘I don’t know about that.’ And then I’ve watched it work.”

Reading the river

But the real key to Angel’s success, several said, is his ability to look at a river and know what’s happening beneath the surface.

“It’s eerie almost, he’s so successful,” said Gabe Watson, a Portland Fire Bureau firefighter and member of its dive team who sometimes accompanies Angel on boat salvages.

Angel said he asks questions from witnesses at the scene that perhaps others don’t. Then he applies what he’s learned to what he sees in the body of water at hand.

“I can read water,” Angel said. “That’s as simple as I know how to say it.”

In spring 2009, for instance, Deschutes County Search and Rescue scoured the Crooked River near Smith Rock State Park looking for 19-year-old Alex Thompson. He tried to cross the river on April 19 and went under.

The day after his disappearance, according to a Bulletin report, divers and searchers on the bank combed a 3 1/2-mile stretch of river. The team also chartered a helicopter to scan the area from above.

A month later, when the water was lower and weather conditions seemed ideal, the searchers returned. Fifty people participated, including 18 divers using underwater cameras. They didn’t find Thompson.

Shortly afterward, Angel volunteered to help.

After scanning the river, Angel decided it was more likely Thompson entered the water upstream from where witnesses said he did. Just about 100 yards upstream was a calmer spot, as opposed to the rushing, rocky place searchers had used as their starting point.

Angel and Geraths began probing the water upstream with a hot stick. They found the young man’s body in 37 minutes, wedged against a rock.

Deschutes County Sheriff Larry Blanton, who has known Angel since his days as a Wasco County sheriff’s deputy in the late ’70s and early ’80s, said Angel shared several hot sticks with rescuers and showed them how they work. He said Angel’s expertise on rivers is unparalleled.

“He thinks about the dynamics of the river, the hydrology, and knows if I do this that will be the result,” Blanton said.

Still, Angel must sometimes get wet.

Beneath the surface

Angel’s methods also go against the grain when he goes underwater.

The cardinal rule in diving, as well as in search and rescue, is always work with a buddy for safety. Angel’s standard is never to go underwater with a partner. Another person changes the water flow, he said, and couldn’t help in a rapid current anyway.

He also goes into water that others would consider way too dangerous.

Watson said the search-and-rescue rule of thumb is to put yourself at risk only if there is a life to be saved, not one already lost. Yet what is considered a risk for most is well within Angel’s ability. After 10 years doing dive search and rescue, Watson said he would be comfortable trying only one-fourth of what Angel does.

Military divers, Watson continued, train in 3 to 4 knots of water current. Angel dives in water Watson estimated at 12 knots.

The method is the difference. Where rescue divers are more likely to put in from a boat, swim to the intended destination and then descend below, Angel often creeps in from the shore.

Especially in whitewater, he keeps to the bottom of the river. Angel said he often shapes himself like an airplane wing in the current.

He never lets go of a line to the surface and he never continues into a section of river where he can’t get a good sense of what is there.

“I’m always in control,” he said. “I’m never a leaf in the wind.”

Watson described it differently. “He’s rock climbing on the bottom of the river.”

While Watson said some consider Angel crazy, he has worked with the salvage diver enough to know that he isn’t an adrenaline junkie. Angel is never in a hurry, and if he is five minutes away from finishing the work but the sun is too low in the sky, he will decide to return the next day.

“I appreciate that about him, because there’s increased risk in a hurry,” Watson said. “That takes a lot of self-control.”

“He’s not really taking risks,” Watson added. “It’s with a method, with a plan, with experience.”

But Angel’s brand of underwater search does mean that no county liability insurance would ever cover him. It means he doesn’t get paid for helping out, and it means that working relationships become crucial.

Angel is the one who calls the shots when he’s on the water, Pearce said. And he’s intense and take-charge in scenarios where sheriff’s deputies are the ones used to being in control.

Pearce said he recognized Angel’s value years ago. But not every search-and-rescue team is so comfortable with him.

“It’s a shame,” Pearce said. “I’ve told more than one search-and-rescue coordinator that if you have a body in the water, he’s your best resource.”

And that is why Angel doesn’t just show up when he hears of someone being lost.

“He understands the politics,” Watson said. “He sits back and waits. He wants them to call him.”

Helping others

It was Pearce who called Angel in July 2006, when Danielle Hagler went missing. The Oregon City girl had been rafting with her church group when she was thrown from the boat at White Horse Rapids.

Pulling through the pain of the fractured leg, Angel said he tried to move Danielle’s body but couldn’t. He tied a rope to her wrist and returned to the surface.

But moments later, Angel’s volunteers lost control of his boat. It sank in the frothy water, the only time he’s ever lost a watercraft.

Kathy Rhodes, Danielle’s grandmother, said Angel and Pearce then talked to the family. They wanted to talk to various agencies to see if they would permit a temporary drop in river levels.

“He told me about the rope, ‘I was just letting her know I was coming back, but it wouldn’t be today,’ ” Rhodes said.

“He understands the value of recovering the body,” Watson said. “He knows the closure for a family that brings.”

Angel’s boat was destroyed. He used another boat to make the rescue a week later. The agencies dropped the flow from Pelton Dam for six hours to assist. Angel refused to accept payment from Danielle’s family, but the family raised money with their church to help him buy a new boat.

Danielle’s family has kept in touch with Angel and his wife over time. The girl’s father and uncle occasionally help Angel out when boats go down.

“We have not legalized anything, but every time we talk we tell them they’re part of our family,” Rhodes said.

In Rhodes’ Oregon City home is a picture of all her grandchildren on Angel’s new boat. He named it “Danielle’s Angel.”

“We have no doubt,” she said, “that Mark was our angel.”

The winter after Danielle’s death, Pearce sucessfully lobbied the Oregon Legislature for a law to require that all boaters in Class III rapids or above wear a life jacket. The law before on private boats only mandated that those 12 or younger wear life jackets. Angel joined Pearce on at least one trip to Salem to testify.

Angel said he’s seen scary things during his years on rivers. He’s seen families with 6- or 7-year-olds in flimsy, big-box store rafts running Class IV rapids. He’s seen families taking their toddlers on rivers, or people in rapids who can’t walk well on land, let alone swim in water.

“My rule is if a kid is not old enough to immediately react to a command, he’s not allowed in a boat,” Angel said.

He hopes people will use more common sense.

“I’m getting tired of going to look for people.”