Explore Utah’s Canyonlands and Arches national parks

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 13, 2015

- Explore Utah’s Canyonlands and Arches national parks

MOAB, Utah — It wasn’t the first time that official maps had failed to give us the information we sought. But we found a first-year ranger at Canyonlands National Park who explained why we couldn’t find directions to a site labeled False Kiva.

The National Park Service maintains a three-tiered system to protect native cultural sites. Class I parks are on all the maps, he said. Class II sites, like False Kiva, are not promoted on maps, but park officials can help you find them.

Trending

“Class III, as far as you and I are concerned, doesn’t exist,” the ranger said.

That was the start of an afternoon adventure that led us down an unmarked wilderness trail, through a boulder field and along a razor-thin ledge above a frightening cliff face. My companion, photographer Barb Gonzalez, with her 25 pounds of camera equipment, demurred on the final scramble, which led up a steep slope of sliding shale fragments to a truck-sized rock.

I squeezed my less-than-slender body around this final obstacle to enter a natural grotto with a shallow circle of carefully stacked rocks, about 8 feet in diameter, at its heart.

From this perch, a panorama spread for many miles to the south, across red-and-white sandstone mesas falling 1,200 feet to the canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers. In the near distance rose the isolated pinnacle of Candlestick Tower, for us a directional landmark as we made the unmarked trek assured of our path only by prior footprints and occasional rock cairns.

Beside me in the grotto, albeit compromised by vandalism from more than a century of visitation by nonnative intruders, were other indications of ancient residence — perhaps by the Puebloan (Anasazi) people, who disappeared from this region about 800 years ago. There were a couple of rectangular walls, seemingly dismantled by rock collectors, and a few pictographs, including a pair of hands. Three holes in a raised clay platform at the rear of the grotto, perhaps once a storage area for grain and corn, had been roped off by park officials.

Puebloan villages typically featured a ceremonial circle known as a kiva. This one merely imitated those larger structures; thus, the “false” designation. Nonetheless, I felt it would have been sacrilegious to enter the circle, so I sat beside it and briefly meditated before signing a log book left by intrepid visitors and turning my attention back downhill.

Trending

Thunder was beginning to rumble, and I glanced lightning beginning to flash across the canyons. Gonzalez was still awaiting my return beside a scrub juniper far below. Together we made the 1.3-mile hike back to the trailhead near Upheaval Dome. The excursion took a good hour in each direction, and we barely beat the encroaching storm back to our car.

Geological wonders

The irascible environmentalist Edward Abbey, whose classic 1968 book, “Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness” remains a best-seller in bookstores throughout the American Southwest, no doubt helped to motivate this foray.

“You can’t see anything from a car,” he wrote. “You’ve got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you’ll see something, maybe. Probably not.”

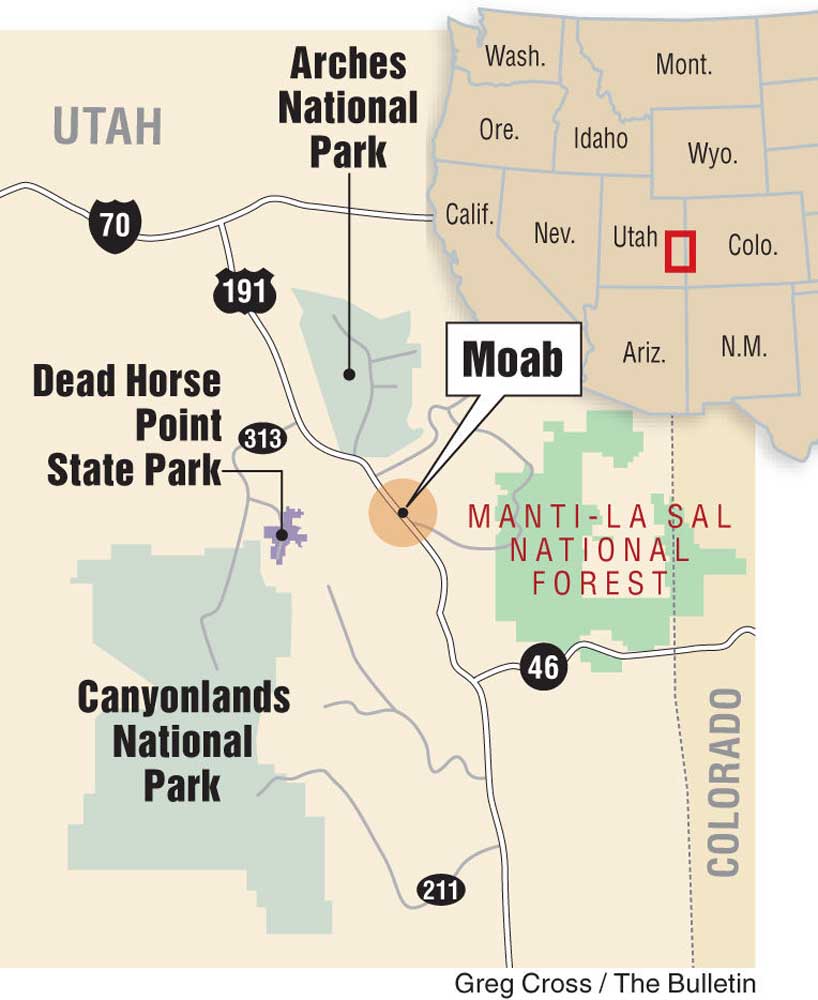

Abbey, who lived most of his adult life in the oasis town of Moab, not far from Utah’s border with Colorado, got his first exposure to desert life in the 1950s in Arches National Park. Arches is a mere 5 miles from Moab (Canyonlands’ entrance gate is 32 miles), and the steep climb into the park is considerably enhanced with the use of one of Abbey’s “contraptions.”

But there’s every reason to leave the vehicle parked at the old Wolfe Ranch, 13 miles above the entrance station and visitor center, to make the moderately strenuous, 1.5-mile hike across a barren slickrock dome to visit the Delicate Arch at sunset.

There are more than 2,000 arches within the 120 square miles of Arches National Park, along with monumental monoliths, grand sandstone fins, pinnacles, spires and balanced rocks perched so precariously on their pedestals they appear ready to topple off at any moment.

Thirty-six miles of paved roads lead to “Park Avenue,” above which loom rocks with names like the Organ, the Three Gossips and the Courthouse Towers; “The Windows,” with their unforgettable Double Arch soaring over the landscape; and the Fiery Furnace, a hazardous maze of red-rock terrain where unwary visitors have so frequently become lost, it’s now recommended for hiking only on a ranger-led walk.

But if Arches has one icon, it’s the Delicate Arch, so renowned that it appears on Utah state license plates. There are viewpoints along paved roads, certainly, but nothing compares to a pilgrimage to the foot of this geologic wonder.

Unlike natural bridges, which are eroded by the flow of water, arches are created with no stream present. In this park, ancient sandstone was thrust upward; vertical cracks formed with faulting and other earth movement; water from rain seeped into the cracks, expanding and breaking them as it froze in winter. Wind finished the job. “This is Arches National Park’s geologic story — probably,” says the park brochure. “The evidence is largely circumstantial.”

Delicate Arch

The intense beauty of Delicate Arch is anything but circumstantial. Before we had even begun the journey to Moab, two days’ drive from Bend, Gonzalez had made this unique geological feature No. 1 on her photographic hit list. And she had designated the last hour of sunlight as her target time to visit.

We parked at Wolfe Ranch about 90 minutes before sundown. The ranch is a thing of the past — John Wesley Wolfe, a disabled Civil War veteran, settled here in the late 1800s to graze cattle and sheep on the abundant grasses with his son Fred — but its remnants survive as a reminder of the pioneering spirit of early visitors. A deeply weathered one-room log cabin, a root cellar and a primitive corral provided them a home for two decades.

The trail from Wolfe Ranch crosses a boggy, intermittent wash. A short distance past the footbridge, a signpost indicates a detour to a panel of rock carvings left by Ute hunters in the 18th or early 19th century. Bighorn sheep were the prey.

But this trek was about arches, not etchings. We began our 480-foot ascent on a rocky but well-marked trail, then clambered across featureless “slickrock” — wind-polished sandstone typical of this region — marked with occasional piles of rocks (cairns) to indicate our route. Getting lost was not an issue: Dozens of others were also making the pre-twilight climb.

About a mile up the slickrock, the steep, barren slope mellowed and briefly leveled. We moved easily across a lightly wooded stretch to a ramp-like ledge, polished by myriad hikers’ boots, for the final 200 yards before emerging upon a bluff top.

And there stood the Delicate Arch. The freestanding formation, rising 65 feet above the surrounding landscape, is all that remains of an ancient fin of Entrada sandstone. Scores of mostly respectful visitors, speaking in a babel of languages, were seated upon the rocks of the natural amphitheater that surrounds the monument, hoping for a show of color at the moment of sunset. Skies that were mostly cloudy seemed to stifle that expectation.

Under any conditions, the Delicate Arch is spectacular. On this evening, nature had a special surprise in store. As the sun began its final plunge to the western horizon, its rays leapt from behind the clouds to shine a piercing beam of light upon the arch. As the solar orb sank from view, the arch seemed to burst into flame, gleaming an almost incomprehensible red-orange in an unlikely contrast to the distant 13,000-foot summits of the La Sal Mountains.

Nature’s art gallery

If Delicate Arch is the photographer’s sunset mecca, Canyonlands’ Mesa Arch is its sunrise counterpart. As the first light of day peeks above the La Sals, it illuminates the underside of this broad, low arch. Gonzalez arose well before dawn and traveled to Mesa Arch in an attempt to capture that spectacle, but cloudy skies blocked the rays of dawn. Still, this arch is worth viewing any time of day, framing the La Sals from a viewpoint just a quarter mile’s walk from a parking area.

For many Moab visitors, Canyonlands is all about the end-of-the-road views. Grand View Point is well-known for the fiery sunset panoramas that extend beyond the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers, a union that culminates in the whitewater rafters’ nightmare known as Cataract Canyon. You won’t see the river activity from here, but you’ll certainly see four-wheel-drive vehicles 1,500 feet below you, on the White Rim Road that circles the lower basins.

Another popular nearby viewpoint above the Colorado is at Dead Horse Point State Park, immediately east of Canyonlands’ north entrance, overlooking a series of pronounced gooseneck loops in the Colorado. It takes its name from natural corrals once used to round up wild horses.

Canyonlands National Park has several distinct sectors: It would be easy to spend a full week (or much more) exploring. By far the most heavily visited district is Island in the Sky, the one nearest to Moab, where we did our exploring. West of the Green River is The Maze, accessible only by four-wheel-drive. Northwest of the main park area is Horseshoe Canyon, whose brilliant rock drawings require hikes of 7 miles or more.

The Needles district, dominated by colorful sandstone spires, is a popular destination for hiking and mountain biking. It covers the park’s southeastern reaches and may be reached via paved highways — 32 miles south from Moab on U.S. Highway 191, then 34 miles west on State Route 211. Along the entrance road, 19 miles off Route 211, is one of the most concentrated collections of ancient petroglyphs in the Southwest: On a cliff wall of about 200 square feet, Newspaper Rock displays a variety of symbols and depictions of human figures and animals.

Our favorite rock panels, however, were in Sego Canyon, and like False Kiva, you may have a hard time locating them on a Utah highway map. Starting from Moab, you’ll want to drive north a half hour to Interstate 70, then turn east for 5 miles and exit at Thompson, which today is little more than a highway junction. A one-lane strip of potholed asphalt leads through the remnants of a village, including an abandoned motel and café, to the north.

One small sign, posted by the Bureau of Land Management, is the only indication that you’re on the right route. A packed-dirt turnout on your left, about 3½ miles north of Thompson, is the best place to park and walk to see the rock art.

Remarkably, three separate native cultures are represented here on adjacent walls. The most recent, perhaps as few as 150 years old, were carved petroglyphs left by the resident Ute tribe. Earlier pictographs, painted with durable natural stains from minerals and plants, were the work of the Fremont culture (Anasazi contemporaries about 1,000 years ago) and the Barrier Canyon people (more than 2,000 years ago).

The oldest paintings were the most remarkable: depictions of giant beings with orb-like eyes, antennae and long earrings, holding squiggly canes that might have been snakes.

Moab recreation

The town of Moab itself, its green valley fringed by the Colorado River and wedged between red rock cliffs, is perfectly positioned as a hub for exploration of this region. Although its population is only about 5,000, it is the largest community in southeastern Utah, and it offers nearly every possible service — dozens of motels and restaurants, a good information center and a regional hospital. The latter may not sound overly important to some, but for those who come to Moab to challenge its renowned mountain-biking routes, it’s a factor to consider.

Moab was first settled in 1878 as an agricultural community at one of the few natural crossings of the Colorado. It was incorporated in 1902, but didn’t really boom until the 1950s, when the growth of America’s nuclear industry — power as well as weapons — made the area’s uranium deposits a valuable commodity. A quarter-century later, as the mines were closing, tourism was on the rise thanks to Moab’s discovery by Hollywood film producers.

Today it is the ultimate desert tourist town, a hub of backcountry activity for hikers and photographers, rafters and kayakers, rock climbers, BASE jumpers, slack liners, and especially mountain bikers and all-terrain vehicle enthusiasts. All over town, outfitters offer organized trips and customized excursions, while bicycle and Jeep-rental operations are legion. The tourist season winds down by November and hotel rates drop substantially after that time.

A popular destination is the Sand Flats Recreation Area just east of town, where both bikers and ATV riders can get a taste of the desert outdoors on the famous, 13-mile Slickrock Trail. Petrified sand dunes — abrasive when dry, very slippery when wet — are challenging to the inexperienced. “Graduates” can continue to hundreds of miles of other trails in Canyonlands-area wilderness and the Manti-La Sal National Forest.

— John Gottberg Anderson can be reached at janderson@bendbulletin.com.