Behind-the-scenes foodie foray in Idaho

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 1, 2015

- Behind-the-scenes foodie foray in Idaho

{%comp-FFFFFE-tl%}

BOISE — Enjoying a good meal is one thing. Knowing where your food came from is quite another.

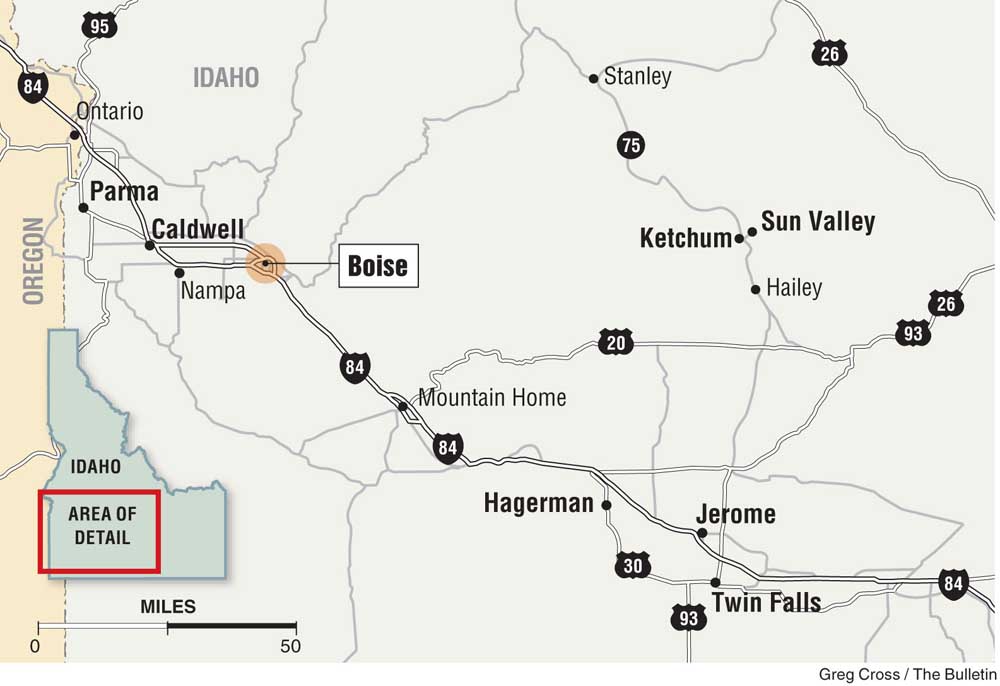

I was fortunate last month to be invited by the United Dairymen of Idaho and the Idaho Division of Tourism to join a small group of food writers on an escorted tour of food-industry providers across southwestern Idaho.

Over the course of three days, we dropped in on a beef feedlot, a dairy farm, an apple-and-peach orchard, the state’s largest winery and the country’s largest trout farm. We paid visits to two test kitchens — one of them exploring a broad swath of vegetable production, the other developing new blends of cheese.

{%pr-4536885%}

We concluded our visit with attendance at the Trailing of the Sheep festival in Ketchum, an annual nod to the historical importance of sheep ranching to the region now best known for its Sun Valley resort.

And although we didn’t even make it to the fields of potatoes, of which Idaho is the nation’s No. 1 producer — the hot, dry summer of 2015 forced an early harvest, so the spuds were already in the warehouses — our group had ample opportunities to discuss agri-business with experts in many fields.

I learned that Idaho is a leading producer not only of potatoes (33 percent of all those grown in the United States), but also peas, barley, sugar beets, onion and peppermint oil, according to the state Department of Agriculture. It is No. 3 in the country in dairy production, the state’s biggest cash crop with $8.3 billion in annual receipts. It follows that forage crops (hay, wheat and corn, for instance) also represent large segments of the economy.

In all, 189 separate products are grown in Idaho, the majority in the vast and irrigable Snake River Plain. Our three-day course through this region took us through the Treasure Valley, on the Oregon border; the Magic Valley, near Twin Falls; and finally into the Sun Valley area.

Morning visits

Our first day began with breakfast at the Simplot Foods test kitchen in Caldwell, 25 miles west of Boise off Interstate 84. Various fruits, eggs, bacon, a potato-arugula scramble, French toast made with pumpkin bread and a huckleberry-Greek yogurt smoothie with apple cider, as prepared by corporate chefs, showcased many of the foods that have made the J.R. Simplot Company one of the Northwest’s agricultural giants and a major player in international markets.

{%pl-4550990%} According to communications manager Ken Day, the company has a three-pronged focus: Agri-business, including the production of phosphates for fertilizers; livestock, with ranches and feedlots that have made Simplot the largest producer of beef cattle in the West; and food production. The latter division is based here in Caldwell where the research-and-development division employs a full-time panel of food testers to double-check creative decisions made by chemists and microbiologists — and chefs.

As we ate, Day described how company founder J.R. (Jack) Simplot quit school in 1923 at the age of 14 and went to work on an Idaho farm. Within six years he had founded a company that quickly grew to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the United States. Simplot’s fame was sealed during World War II, when he first sold dehydrated potatoes and onions to American troops overseas, then invented frozen French fries.

Today the company, still in family hands (J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at the age of 99), produces 3 billion potato products each year. “We’re sure we have a potato for everyone,” Day said.

Our second stop was the Symms Fruit Ranch, established as an 80-acre homestead more than a century ago in Caldwell’s Sunny Slope neighborhood. Today it has grown to 5,000 acres, 3,500 of which are planted with trees — about one-third of them apples, one-third peaches and cherries and the balance plums, pears, nectarines and apricots.

Company vice-chairman Jim Mertz, who married into the Symms family, represents the fourth generation of family ownership. He and fifth-generation marketing specialist Sally Symms walked us through a section of orchard, encouraging us to pick Granny Smith apples from the trees and enjoy sweet, crunchy bites as we did so.

{%pr-4536904%}

While a large share of Symms fruit is sold locally, Mertz said, whole fruit is also exported to 42 separate countries. Cherries and white peaches are especially popular in Taiwan, he said. Mexico and Central America are major apple importers, along with Finland, where they are a popular Christmas holiday gift, Sally Symms said.

Wine and beef

At the Ste. Chapelle Winery, we met winemaker Maureen Johnson. “I’m the queen of sweet wines,” said the woman who has been producing wines at Idaho’s largest winery since 1981. She became head winemaker in 2010.

Founded in nearby Emmett in 1975, Ste. Chapelle moved just three years later to its landmark building — modeled after the Queen’s chapel at the Cathedral de Notre Dame in Paris — in the Lake Lowell area south of Caldwell. Now owned by Precept Wines of Seattle (along with its sister Sawtooth Winery), Ste. Chapelle is well known for Rieslings among its annual production of 120,000 cases.

In all, however, the vineyards produce 15 separate wines, including a wide range of reds in small lots: cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, merlot, syrah, Malbec, tempranillo, petit verdot and petit syrah. Its inventory also includes chardonnay, chenin blanc and sauvignon blanc. Vineyard manager Dale Jeffers — “I’m the farmer, I just deliver the product,” he declared — said 2014 was the winery’s “best year ever” in terms of quality and numbers.

Boise Valley Feeders, outside of rural Parma, prepares 45,000 beef cattle each year for market. Its parent company, Agri-Beef, represents two associated brands, Snake River Farms and Double R Ranch, widely served in restaurants in Oregon and elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest.

A spokesperson explained that cattle arrive at the 800-acre feedlot at about nine months of age, weighing about 800 pounds. They are sorted, vaccinated, wormed and implanted with a growth hormone, but “our priority is to keep the animals calm and quiet,” the spokesperson said. Straw, hay and a coarse corn mix comprise the diet, along with various liquid supplements. When the cattle are trucked to Toppenish, Washington, 140 days later for “processing” (a euphemism for “slaughter”), they weigh nearly 1,500 pounds.

At any given time, we were told, there are about 23,000 cattle on the lot. Most are crossbred — Angus, Simmental and Charolais, sometimes with Hereford or other breeds. Upon processing, intramuscular marbling determines the grade of beef; over 90 percent is determined to be choice or prime, the spokesperson said.

Trout and cheese

The next morning, after dinner in Boise, our group of writers traveled down the Thousand Springs Scenic Byway, through the Snake River Canyon, to the small city of Twin Falls. Our first stop was Clear Springs Foods, the world’s largest producer of freshwater rainbow trout.

{%pl-4536942%}

Fed by natural springs that emerge through basaltic cliffs from a massive underwater reservoir, the Clear Springs hatchery boasts water with a high dissolved oxygen content that flows at 58 degrees year-round. “The springs are the reason we’re here,” said Clear Springs’ director of research and development, Dr. Scott LaPatra.

LaPatra walked us through the company’s research labs, describing selective breeding programs, quality-control regulations and environmentally friendly foods. “We know exactly what our fish eat, so we control the entire product,” LaPatra said. “The diet is nutrient dense, 45 percent protein and 20 percent fat.”

The trout, LaPatra said, are the company’s own unique strain. These Clear Springs rainbow trout are tricked into year-round spawning, he said, and are vaccinated for resistance to bacteria and viruses. “No one else is doing mass vaccinations with our unique means,” the research director said.

Marketing director Curt Myers said trout farming began in this area in 1944, and Clear Springs Foods was established in 1966. Today it produces more than 50 percent of all rainbow trout farmed in the United States, he said — about 20 million pounds each year. Eighty percent of that is frozen as boneless fillets.

As we walked through the hatchery area, LaPatra confessed that the company must take special care in spring to protect its young fish from flocks of pelicans. “If they get into a raceway,” he said, “they’ll take so many fish that they can’t get out.”

{%pr-4536943%}

In Twin Falls, we made a brief stop at the Glanbia Foods’ Cheese Innovation Center. An Irish company that established a U.S. presence in 1989, Glanbia processes 26 million pounds of milk a day for wholesale markets worldwide, according to research manager Ram Kumar.

“Our emphasis is on innovation,” Kumar said. Some of that work, he said, is in response to specific requests, such as one from a company in search of sliced bleu cheese. “We added flavor and color to Monterey Jack, and found a plant-based product additive that retains color,” he recalled. “Now they have an exclusive product.”

Calves and sheep

Twin Falls is the heart of a region called the Magic Valley, in part because of the Thousand Springs — but also, perhaps, because it is the hub of a dairy farming region that ranks behind only California and Wisconsin in national production.

Our visit to Si-Ellen Farms, outside of Jerome, gave us a close look at modern dairy-farming practices. Bruce Whitmire, the herd health manager, described a variety of high-tech apps that monitor cow behavior, including pedometers that measure their movements.

{%tl-F5E5CC, 000000, 2%} Founded by a Swiss family in 1935, Si-Ellen relocated in 1990 to its current acreage, which is ringed by a 3½ mile road. It milks 7,200 dairy cattle daily — 100 at a time, in seven minutes or less.

In addition, Whitmire said his crew delivers an average of 50 calves a day. We watched as one was pulled from his mother’s womb at the end of a 272-day gestation period. “Last month, we delivered 1,330 babies,” said Whitmire, “and we have 2,300 on bottles at any one time.”

The next day we were in Ketchum, north of Twin Falls and adjacent to the famous Sun Valley resort. The occasion was the annual Trailing of the Sheep Festival.

Before railroad baron Averell Harriman established Sun Valley in the 1930s, the Big Wood River Valley was the country’s No. 1 sheep ranching region. During the years of World War I, due to demand for wool, lamb and mutton, the sheep population reached more than 2.6 million, nearly six times Idaho’s human population.

“Millions of sheep covered the mountains and the valleys of the area,” wrote historian Sandra Hofferber. “Every spring the stockmen would head their herds for the mountains, and every fall they would return with their ewes.”

{%pr-4537087%}

Although the modern sheep population is down to about 15,000, October’s Trailing of the Sheep Festival recalls the days when sheep descended en masse from the Pioneer Mountains and thundered through the streets of Ketchum. Today the stockmen and their dogs, who continue to herd their flocks down Idaho State Route 75, are joined by Basque dance troupes that joyously recall the contributions made by their forefathers, who fled political turmoil in Spain to run with the sheep in Idaho.

The largest lamb supplier in Idaho today is the Lava Lake Ranch near Hailey, south of Ketchum. As the parade of sheep ended, the company offered a lamb barbecue to celebrate their woolly stock in their own way.

— Reporter: janderson@bendbulletin.com

{%ssc-4537092,4537096,4537082,4537064,4537044,4536941,4536911,4536907,4536901%}