Business successes turn to philanthropy

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, February 11, 2015

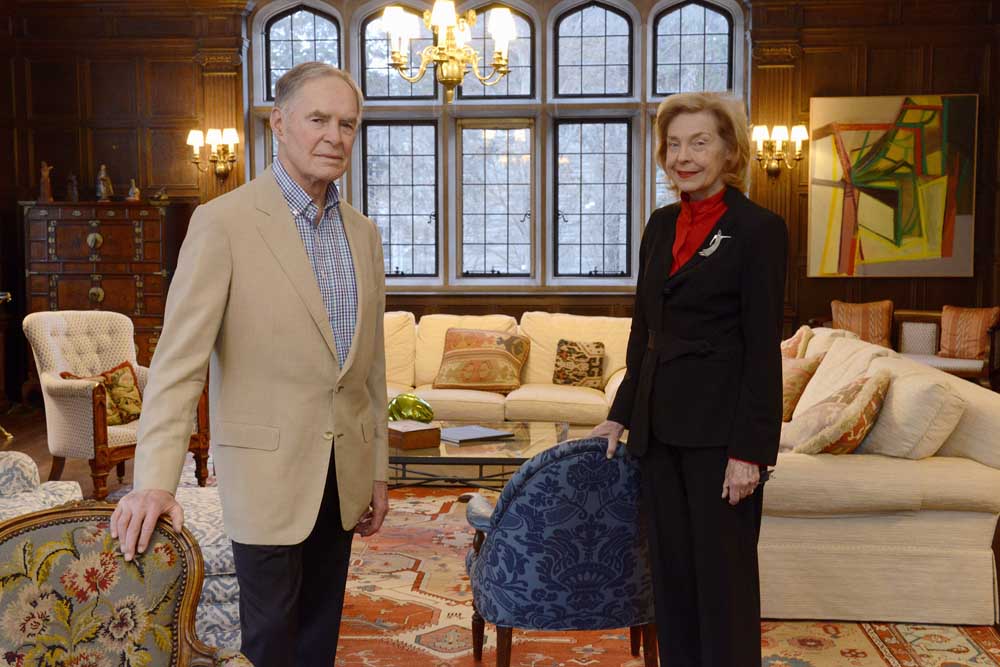

- Rebecca Droke / Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via TNSJeffrey and Jacqui Morby, here at their home in Pittsburgh, started the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund with several other families. The fund has given more than $27 million to Alzheimer’s research.

PITTSBURGH — As a banker, Jeffrey Morby soared to the top — with jobs running international operations for the Bank of Boston and later for Mellon Bank, then based in Pittsburgh and from which he retired as vice chairman in 1996.

But the demands of his full-time career didn’t leave time to publish a book he wrote in the 1980s about a scientific topic that’s fascinated him for much of his life: the workings of the human brain.

Although he never published that book, he’s delving deep into one of the most widespread and devastating brain diseases in the world as co-founder and chairman of the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund. He, his wife and several other families launched the charity in 2004 with $1 million, and in 10 years it has sunk more than $27 million into research that aims to prevent or reverse the disease.

Donors’ money goes directly into cutting-edge research that a scientific team is conducting at Harvard and about 25 other institutions. People familiar with the fund say it’s unique as a philanthropy because its founders and board members pay for all overhead and operating expenses.

“That’s unusual, because most organizations don’t have that kind of dedicated founder that cares so much,” said Carolyn Duronio, an attorney who helped Morby and his wife, Jacqueline, a retired venture investor, set up the fund. “Both of them are really, really dedicated to this cause.”

The nonprofit has raised $48.3 million since its inception, including $11 million raised in 2014.

Before they started the fund, the couple were searching for a way to channel some of their private family foundation’s assets into “an area of concentration that was meaningful to human kind,” said Morby.

Through his interest in the brain, he in 2004 met Rudolph Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Harvard and director of the genetics and aging research unit at Massachusetts General Hospital. From their discussions, Morby concluded, “Alzheimer’s was decimating the world and there was no money to fund” the research.

Alzheimer’s affects about 5 million people in the U.S. and has no cure. Although it’s hard to track the total amount of money being spent on research worldwide, the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, allocated an estimated $566 million for Alzheimer’s research in its 2014-15 budget, and the Chicago-based Alzheimer’s Association said it has spent $335 million on more than 2,000 research projects since 1982.

Tanzi is now Cure Alzheimer Fund’s lead researcher and was a lead scientist on a project that Morby touts as among the fund’s most significant breakthroughs. In “Alzheimer’s in a Dish,” Tanzi and a colleague grew human brain cells in a gel in a petri dish and gave the cells genes for the disease so the scientists could observe how it progresses and how drugs can treat it.

Other accomplishments to date that fund officials consider to be significant include development of a Web-based Alzheimer gene database and findings that show Alzheimer’s is likely an autoimmune disease triggered by innate immunity in humans.

The fund has a staff of three full-time employees and five part-timers who work out of offices in the Boston area.

Instead of the traditional scientific peer-review process, Morby said, Cure Alzheimer’s scientific advisory board reviews proposals and projects that come directly from researchers. Approval can sometimes be accomplished in a matter of a weeks.

“We can get done in a month what can take two years for other foundations,” he said.

Max King, president and chief executive of the Pittsburgh Foundation, credits the fund’s rapid growth and research accomplishments to the Morbys’ distinctive approach.

“Each of them had very, very successful high-powered careers in business. They did more due diligence and research in getting this started than you can imagine. They are both such deep thinkers. They both got extraordinary results in their business careers and translated that to philanthropy.”