’Virtual Unreality’: Online, the lying is easy

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 6, 2014

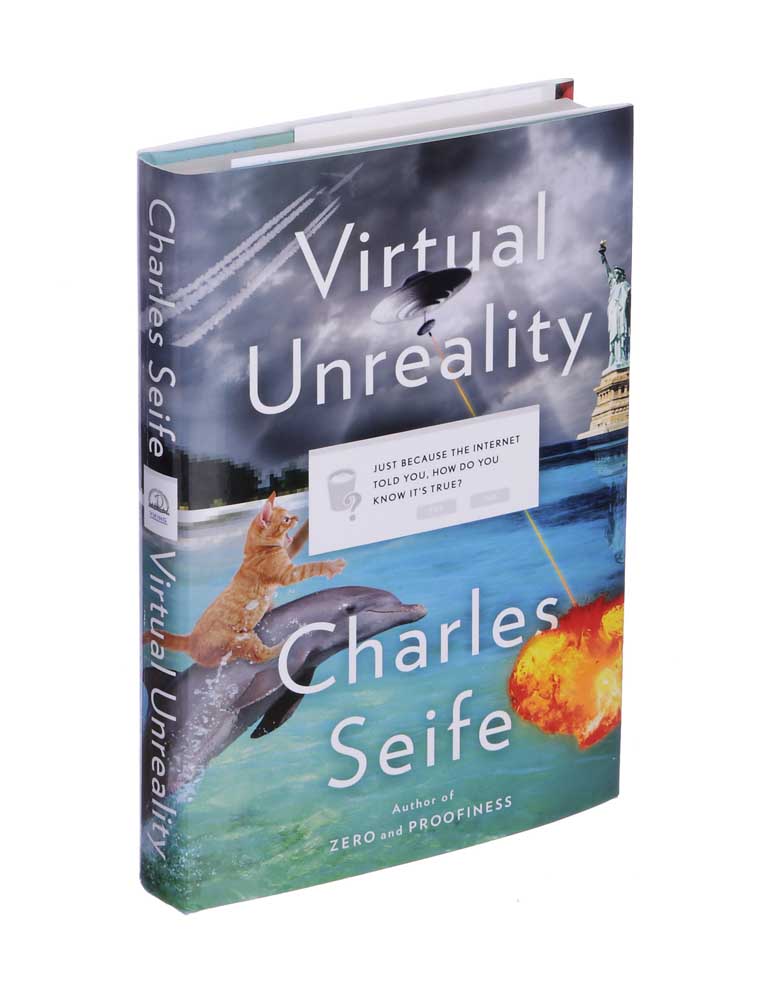

- James Nieves / New York TImes News Service"Virtual Unreality" by Charles Seife

“Virtual Unreality: Just Because the Internet Told You, How Do You Know It’s True?” by Charles Seife (Viking, 248 pgs., $26.95

Charles Seife is a pop historian who writes about mathematics and science, but his abiding theme, the topic that makes his heart leap like one of Jules Feiffer’s dancers in the springtime, is human credulity.

In “Sun in a Bottle” (2008), he observed the scientists who chased low-temperature fusion down the rabbit hole. In “Proofiness: The Dark Arts of Mathematical Deception” (2010), he delivered his thesis in his first sentence: “If you want to get people to believe something really, really stupid, just stick a number on it.”

Seife’s new book, “Virtual Unreality,” is about how digital untruths spread like contagion across our laptops and smartphones. The author is unusually qualified to write on this subject, and not merely because his surname is nearly an anagram for “selfie.”

A professor of journalism at New York University, Seife is a battle-scarred veteran of the new info wars. When Wired magazine wanted to investigate the ethical lapses of its contributor Jonah Lehrer, for example, it turned to Seife, whose report pinned Lehrer, wriggling, to the plagiarism specimen board.

Seife has also been targeted, unsuccessfully, by the conservative sting artist James O’Keefe. “O’Keefe and Lehrer”: the title of hell’s own news hour.

A virtual pathogen

In “Virtual Unreality,” Seife delivers a short but striding tour of the many ways in which digital information is, as he puts it in a relatively rare moment of rhetorical overkill, “the most virulent, most contagious pathogen that humanity has ever encountered.”

Mostly, he has a lighter touch, though every so often, he pounds his ideas so remorselessly that he makes you wonder why we online addicts aren’t all twitching and frothing at the mouth like Gwyneth Paltrow in “Contagion.”

One of Seife’s bedrock themes is the Internet’s dismissal, for good and ill, of the concept of authority. On Wikipedia, your Uncle Iggy can edit the page on black holes as easily as Stephen Hawking can. Serious reporting, another form of authority, is withering because it’s so easy to cut and paste facts from other writers, or simply to provide commentary, and then game search engine results so that readers find your material first.

Seife worries about how easily fringe ideas find purchase on the Internet, where previously they’d have perished from lack of oxygen. He writes about how the South African government was persuaded by HIV-denialist websites to forgo providing essential antiretroviral drugs to those who were sick. He writes: “Three hundred thousand deaths might be the most extreme consequence of a Google search gone wrong.”

Sock puppetry

Seife is witty on the many varieties of sock puppetry, the dismal online art of pretending to be, for personal gain, someone other than who you are. One variety of this is to cower under a pseudonym while shivving your enemies. Witness the British historian Orlando Figes, who attacked his rival’s books on Amazon, while writing glowing reviews of his own. He was found out and humiliated, and he agreed to pay damages to some of his victims.

Then there are sock puppeteers who fabricate phony personas to acquire authority or sympathy. It has become so common for bloggers to fabricate young people with terrible diseases, the author notes, that this syndrome now has a name: “virtual factitious disorder” or “Munchausen by Internet.”

Seife sums up how these stories tend to go: “Create a sock puppet or two, give it a tragic problem that will garner sympathy, and then commit ‘pseuicide.’ It’s almost guaranteed to cause a big stir.”

Seife also dilates here upon scam artists, photo manipulators, flash trading on the stock market, the promulgation of “bimbots” (fake online women created to lure lonely men) and the primordial idiocy of sites like Foursquare, which encourage you to tell people where you are to earn meaningless badges.

“People don’t think twice,” he writes, “about reflexively transmitting their whereabouts to a company that’s trying to bend your mind and make you a frequent visitor to your local Pizza Hut, Hess gas station, or RadioShack.”

He has more to say about social media sites. “A decade ago, if a corporation asked for the email addresses of all of your friends and family members, you’d almost certainly have refused,” he says. “But nowadays, people are happy to hand their entire email contact list over to LinkedIn or Facebook or Google or Pinterest or any other site that convinces people to sell out their closest acquaintances in hopes of increasing their own social status.”

While little in this volume is new, Seife is an adept consolidator of information, and he has a choosy shopper’s knack for selecting fresh anecdotes and examples.

I’ve been burned enough times by bad online information (fake quotations, bogus tweets, GPS glitches, Wikipedia howlers) that I’d like to think I don’t require Seife’s advice to pay close attention while surfing. My hokum detector is mostly set at Defcon 1 or 2.

Once a month or so, I’m burned anyway. “Virtual Unreality” is a talisman we gullible can wield in the hope that we won’t get fooled again.