Solar observer drawn to sunspots for 40 years

Published 5:00 am Saturday, November 2, 2013

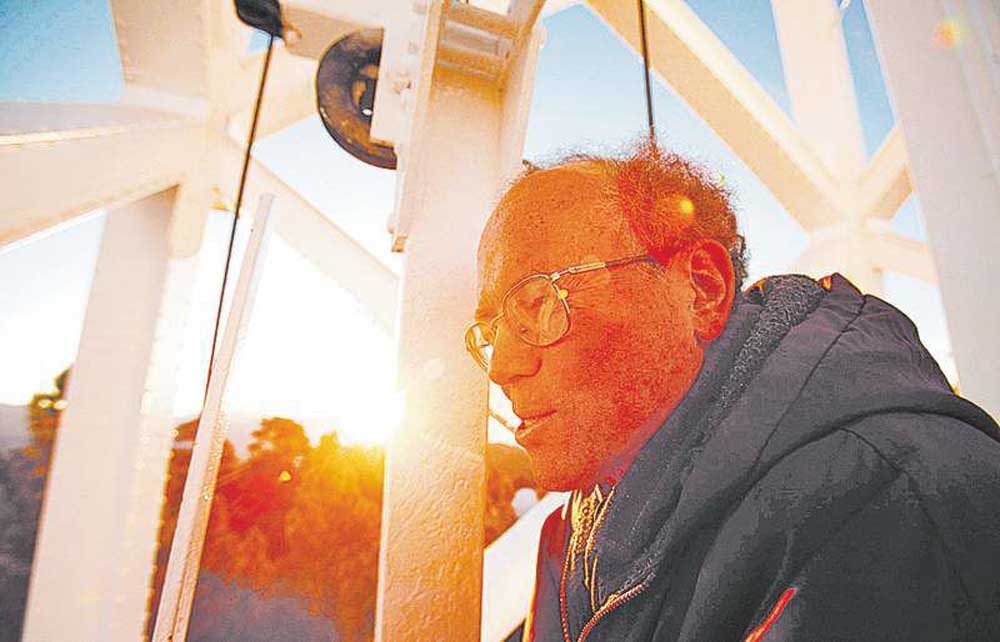

- Astrophysicist Steve Padilla rides in a small lift to the top of the solar observatory on Mount Wilson, Calif., where he charts sun spots.

LOS ANGELES — The elevator is less an elevator than an open-air bucket. In high winds, it wobbles and sways like an old amusement park ride. Today the air is still.

Steve Padilla clips on his safety harness and crouches on a small ledge inside the bucket. He yanks the tiller rope; the winch engages, and the century-old contraption begins its two-minute ascent 150 feet to the top of the tallest solar telescope on Mount Wilson.

The sun, low and bright in the east, has washed away the pastels of dawn and cuts across the top of the forest. A maroon windbreaker wards off the morning chill. Only once, Padilla says, has the bucket stalled, leaving him stranded mid-journey.

He’s been making the trip for nearly 40 years, through Santa Anas and cold snaps, budget cuts and shifts in research. Throughout it all, one part of the job has remained constant: the drawings.

Like cloistered monks in the Dark Ages who devoted hours of their lives to creating manuscripts that few could read, Padilla draws, maps and classifies the sunspots that have formed on this familiar star, adding to almost 28,350 daily drawings that date back to 1917.

Only fire, repairs and inclement weather have interrupted the record of the sunspots, which were once blamed for grain shortages and stock market runs and are now predictors of damaging solar flares.

Partially hidden by oaks and pines, the solar telescope sits inside a tower that resembles an oil derrick, girders crisscrossing above a small concrete bunker and tapering to a freshly painted white dome.

Completed in 1912, it is the legacy of George Hale, the learned astronomer who believed that from this vantage the mysteries of the sun could be revealed. In less than 10 years, Hale built three solar telescopes on Mount Wilson, each more powerful than the last.

Once at the top, Padilla locks the bucket into place and climbs a ladder 10 more feet into the dome. With the push of two buttons, its curved steel panels begin to part.

Sunlight floods the platform. A raven glides by. Mountain peaks, as far south as Mexico, ripple the horizon, and Los Angeles looks like a topographic map, its skyscrapers not worthy of their name.

“There’s a slowdown on the 210,” Padilla says, glancing at the westbound lanes shimmering with cars more than 5,700 feet below.

Life at the observatory

Padilla, 63, grew up in Azusa. As a boy, he studied these mountains, and as an amateur astronomer, he knew someone who knew someone and got a summer job at Mount Wilson in 1974. Two years later, he ditched the promise of a degree in television broadcasting from Cal State L.A. and came to work at the solar tower.

Today he lives alone in a small home on the grounds of the observatory. He stargazes at night and watches old black-and-white movies on an outdated Laserdisc player. Once a week, he drives down the mountain to pick up groceries, have dinner with friends and go to church.

Since 1917, nearly 20 astronomers and technicians have been employed, first by the Carnegie Institution and then by UCLA, at the solar tower. Aside from drawing sunspots, their other job has been to measure the strength of the sun’s magnetic field and the speed of its moving atoms, tasks accomplished by a 40-year-old Raytheon computer that went on the fritz earlier this year.

Until it gets replaced, Padilla keeps busy uploading the decades-old sunspot archive to a UCLA website.

The sunspot drawings are used by the Space Weather Prediction Center in Boulder, Colo., to help forecast solar flares. The agency correlates findings from Mount Wilson with similar observations from Australia, Italy and New Mexico.

Telescopes and cameras on spacecraft can see more detail than the solar telescope, but the human eye is better at identifying subtle features of each sunspot, says UCLA professor emeritus Roger Ulrich, who oversees the 150-foot tower telescope.

The more refined the image, he says, the more accurate the classification of the sunspots that might lead to solar flares.

“The problem is, we don’t know what’s going on inside the sun,” Ulrich says. “The drawings won’t answer that, but they can help us understand the cyclical nature of sunspots.”

Watching sunspots

Standing in the open dome, Padilla adjusts two mirrors that aim the sunlight through a lens down a narrow shaft to the bunker, reducing the diameter of the sun from 865,000 miles to 17 inches.

After the two-minute bucket ride down, he steps into the observing room, which looks like a cluttered garage. Tools and dusty books cover cabinet shelves. Hand-written notes identify electrical switches. Computer parts lie on the floor.

A red Craftsman toolbox serves as the pedestal for a plaster bust of Hale. Photographs of Einstein and his contemporaries hang on the walls, and the visitors log records Stephen Hawking’s visit on June 2, 1990. Twenty-two years later, a NASA intern rode those coattails with “I signed the book Stephen Hawking signed.”

“Now,” says Padilla, stepping up to the observing table that dominates the room, “let’s see what the sunspots have done today.”

This day’s sunspots are just a little smaller than the Earth, and nothing like those that darkened the sun’s surface on April 6, 1947, which are considered the largest ever recorded, the size of which dwarfed Earth and Jupiter.

He ranks the clarity of the image, giving it a 2.0 today. The top grade — a 5.0 — means the sun is as sharp as an engraving. A 1.0 is as fuzzy as the whirling blade of a circular saw.

After a series of calculations reminiscent of high school logarithm exercises, Padilla rotates the observing table so that the top of the paper aligns with the sun’s north pole.

He knows the job isn’t flashy. There will be no major discovery coming from this work, but he likes the tradition, this convergence of science and art.

“The value,” he says, “is not so much in the individual achievement but in maintaining the daily record.”

But that record is in jeopardy, Ulrich says. The telescope’s annual budget of $250,000, cobbled together with grants from NASA and the National Science Foundation, runs out in the spring, and Ulrich says odds of getting more money from NASA are long.

Ulrich won’t speculate on the fate of the solar telescope if funding isn’t found, and he is certain he won’t find money to support the drawings alone.

“The continuity is nice, but it does not carry the day,” he says.

“People feel bad when a long-running program has to stop, but that does not get the funding renewed.”

Should the solar telescope close, Padilla imagines he’ll retire — and then see if he can continue to draw the sunspots as a volunteer.

Drawing the record

After setting up his equipment, Padilla slips a sheet of 10-by-20-inch paper into the disc of light.

After drawing the outline of the sun with a compass and marking the longitude, Padilla opens a rectangular box with four turquoise drawing pencils — 2B, 6B, 5H and 9H — soft to hard lead, some with sharp edges, some with dull.

He shifts between pencils as he traces each sunspot’s penumbra, the soft gray edges, and the umbra, the black center, with a precise stippling motion of his hand.

When he’s done, he opens a panel in the observing table to a pit that was dug before the telescope was built. The air smells like a cave, and sunlight falls 80 more feet to a special plate that breaks the light into a rainbow. By analyzing the spectrum, Padilla can measure the strength of each sunspot’s magnetic field.

When he’s done, he annotates the drawing and finishes with a flourish borrowed from other observers since 1917. He adds his initials to the daily record:

2013, Monday the 30th of September, 16:30 UT, Seeing equals 2.0, SP