High-cost drug deepens debate on Medicare drug coverage

Published 12:00 am Friday, August 8, 2014

A revolutionary new drug for hepatitis C is causing a huge dilemma for many doctors who would love to give it to their patients but are wary of its $1,000-per-dose price tag.

“It’s really been a bittersweet situation,” said Laurie D’Avigno, an infectious disease specialist at Bend Memorial Clinic, who estimates about 10 to 15 percent of her patients have hepatitis C. “We’ve been very excited to have (Sovaldi), but its cost has limited the people who are eligible for treatment.”

Since it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last December, Sovaldi has also raised concerns among public health advocates who are worried its high cost may bankrupt Medicare when the country’s 37 million baby boomers are turning to the system for their health care needs.

“This should be a wake-up call,” said Joe Baker, president of the Medicare Rights Center and one of the main advocates of a multitiered proposal that would give Medicare the tools it needs to get the best prescription drug prices for its 50.7 million beneficiaries.

The drug

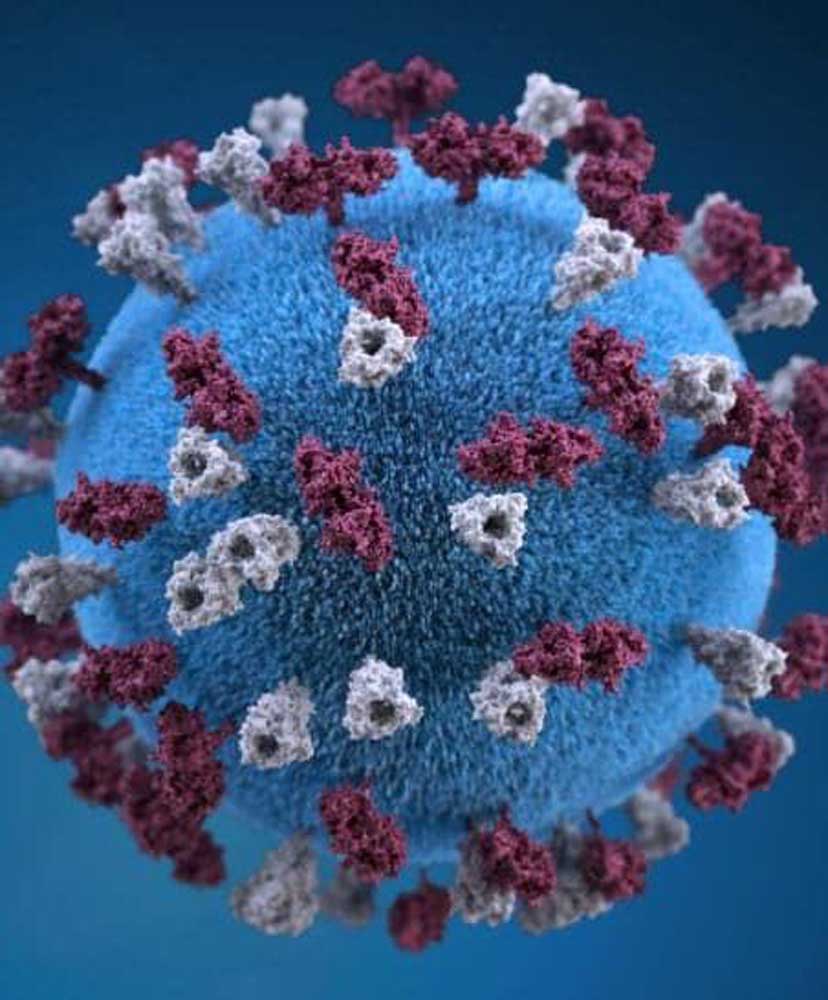

Caused by a virus that is spread through the blood, chronic hepatitis C is an infection that can lead to liver disease (80 percent of the cases) and cirrhosis of the liver (7 percent to 20 percent of the cases.)

It is the leading cause of cirrhosis of the liver, according the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and kills about 15,000 people in the U.S. each year.

Federal health officials estimate more than 3.2 million Americans have chronic hepatitis C, even though many of them don’t know it because they may not look or feel sick.

They are especially worried about its prevalence among baby boomers — who may have received a blood transfusion before blood was routinely screened for the virus or engaged in a risky behavior known to spread the virus, such as using intravenous drugs. Officials are asking people born between 1946 and 1964 to get tested for the disease even if they don’t have any symptoms.

“We have seen an increase in the number of people who are being sent to our office for hepatitis C,” D’Avignon said, explaining these public health warnings and their media coverage are prompting more and more people to be tested for the virus when they see a primary care doctor or visit a local clinic.

She said the age distribution of her new patients “kind of covers the spectrum” between young and old. But it does lean heavily toward people who are in their 50s and 60s and will be relying on Medicare for their health care coverage over the next 10 to 15 years if they aren’t in the system already.

D’Avignon said hepatitis C can be treated with a 24- to 48-week prescription drug regimen that includes the nucleoside inhibitor Ribavirin and Interferon, an injectable drug consisting of synthetic proteins that help the body fight infection and boost its immune system. But this treatment regimen is also plagued with side effects, including flu symptoms.

D’Avignon said this means her patients run the risk of suffering these flu-like side effects every week over the course of a 48-week treatment. They could also experience a decreased blood platelet count, a decreased white blood cell count and increased fatigue over the time that they use the drug.

She said Sovaldi revolutionizes this situation because it shortens the amount of time people need to take their drugs from 24 to 48 weeks to 12. Clinical trials also show that 50 percent to 90 percent of the patients who took Sovaldi experienced a sustainable virulogic response — a point where the virus is undetectable and its symptoms disappear — at the end of their treatment.

But there is one drawback to Sovaldi: Its cost.

When the FDA approved Sovaldi, drug maker Gilead Sciences announced plans to sell 28-pill bottles of the drug for $28,000. According to Gilead’s own estimates, this means the total price of a 12-week treatment featuring Sovaldi, Pegasys (a type of Interferon) and Ribavirin comes to about $94,078 per person.

“The cost of Sovaldi is a big deal,” D’Avignon said, explaining the drug’s price and her patients’ ability to afford it — whether they have health insurance or not — have greatly limited the number of people she can prescribe it to.

Sovaldi’s price, and the prevalence of hepatitis C among boomers, is also raising concerns among many Medicare activists who see it as a reason to fundamentally change how Medicare pays for prescription drugs.

The plans

When it passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, the U.S. Congress created a system of privately managed prescription drug plans known as Medicare Part D plans, which offer prescription drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries.

Each of these Part D plans can choose which drugs it covers, what areas it serves and how much it charges its members in terms of their prescription drug co-payments, premiums and other fees.

According to Medicare’s website, 28 of the 33 Medicare Part D plans that serve Central Oregon have offered some type of coverage for Sovaldi since it was approved by the FDA and later by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

These plans list the medication as a nonapproved brand name or a specialty drug and require their beneficiaries to pay between 65 percent and 75 percent of its cost out of their own pockets.

But according to Stacy Sanders, federal policy director for the Medicare Rights Center, once a Medicare beneficiary has spent more than $4,550 of his own money on prescription drugs — which is Medicare’s current catastrophic coverage cap — the program automatically covers 95 percent of total drug costs.

“Covering Sovaldi could be exorbitantly expensive for beneficiaries and the taxpayers,” Sanders said, citing a study that found covering this and other high-priced hepatitis C drugs could cost the federal government an extra $2.9 billion to $5.8 billion next year alone. That study, conducted by the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, also found the cost of these drugs could force Medicare Part D providers to increase their premiums by $17 to $33 per beneficiary per year.

But rather than ban Part D providers from covering Sovaldi or limit who has access to the drug, Sanders said, one possible solution to this cost problem would be to change how Medicare pays for its prescription drugs.

“It’s been a long-standing ask that the U.S. Congress help us secure better prices for prescription drugs,” she said, explaining the cost of prescription drugs has been a concern long before Sovaldi was invented.

Sanders said part of the problem lies with the fact the Medicare Modernization Act barred Medicare officials from entering into negotiations with drug makers, either on their own or with representatives from their Part D providers.

“There’s a long-standing belief that if Medicare had a seat at the bargaining table,” she said, “it could use its buying power to secure better prices and discounts on prescription drugs.”

Through direct negotiations with drug manufacturers, Sanders said, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has secured a 40 percent discount on Sovaldi for its beneficiaries, and state Medicaid programs such as the Oregon Health Plan get a 23.1 percent discount on brand-name prescription drugs.

She said doing away with the Medicare Modernization Act’s anti-negotiation provisions is also a very popular idea — one poll found 86 percent of independents, 81 percent of Democrats and 70 percent of Republicans support it — so it is no surprise there are a handful of bills seeking to restore this power making their way through the U.S. Congress.

One of these proposals, the Medicare Prescription Drug Choice and Savings Act, would also give Medicare the ability to administer its own prescription drug plan, which would compete with the privately managed ones.

Beyond giving Medicare a seat at the bargaining table, Sanders said, Congress could also help bring down Medicare’s prescription drug costs by restoring a series of discounts promised to duly eligible beneficiaries — people who had Medicare for their health insurance and Medicaid for their prescription drug coverage — that were taken away when the Part D plans started offering drug coverage to all Medicare beneficiaries in 2006.

She said this policy change, which is contained in a piece of legislation U.S. Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., introduced last week, could save the federal government $141.2 billion over the next 10 years.

But regardless of what measure moves forward, Sanders said, something has to be done and done quickly because Sovaldi isn’t the first high-cost prescription drug the Medicare program has had to deal with and it certainly won’t be the last.

“We have to ask ourselves some questions,” she said. “What happens when there’s a cure for cancer? What happens when there’s a cure for Alzheimer’s disease? Are our (prescription drug plans) sustainable and will they be able to afford these costs?”

— Reporter: 541-617-7816, mmclean@bendbulletin.com